Editor’s Note: The following report and the above video were originally published by MintPress News.

In November 2018, I became aware of the case of Kirill Vyshinsky, a Ukrainian-Russian journalist and editor imprisoned in Ukraine without trial since May 2018, accused of high treason.

Soon after, I interviewed Vyshinsky via email. He described his arrest and the accusations against him as politically-motivated, “an attempt by the Ukrainian authorities to bolster the declining popularity of [then] President [Petro] Poroshenko in this election year.”

Vyshinsky noted that his arrest was advancing the incessant anti-Russian hysteria now prevalent among Ukrainian authorities, as he holds dual Ukrainian and Russian citizenship. He noted that the charges against him, which pertain to a number of articles he published in 2014 (none of them authored by Vyshinsky), became of interest to Ukrainian authorities and intelligence services four years after they were published. To Vyshinsky, this supports the notion that neither the articles nor their editor were a security threat to Ukraine, instead, he says, they were a political card to be played.

In early 2019, I traveled to Kiev to interview Vyshinsky’s defense lawyer Andriy Domansky about the logistic obstacles of his client’s case. Domansky viewed the Vyshinsky case as politically motivated and expressed concern that he could himself become a target of Ukraine’s secret service for his role in defending his client, an innocent man.

Domansky told me at the time:

The Vyshinsky case is key in demonstrating the presence of political persecution of journalists in Ukraine. As a legal expert, I believe justice is still possible in Ukraine and I will do everything possible to prove Kirill Vyshinsky’s innocence.”

To the surprise of those following the case against Vyshinsky, in late August 2019 he was released with little fanfare after serving more than 400 days in a Ukrainian prison but still faces all of the charges brought against him by the Ukrainian government and is “obliged to appear in court or give testimony to investigators if they deemed it necessary.”

By early September, Kirill Vyshinsky was on a plane to Moscow. Despite never being tried or officially convicted, he found himself the subject of a prisoner exchange between the Russian and Ukrainian governments.

I interviewed Vyshinsky in Moscow in late September. He told me about his harrowing ordeal, the Ukrainian detention system, other persecuted journalists, and what lies ahead for him.

He also touched on the inhumane conditions he experienced in Ukrainian prisons. He noted that a pretrial detention center as we know it in Western nations is a very different entity in Ukraine and that Ukrainian prisons were so over-crowded that it was common for inmates to sleep in three shifts in order to allow enough standing room for inmates crammed into a cell.

Ukrainian Prisons Like a ‘Concentration Camp’

Aleksey Zhuravko, a Ukrainian deputy of the Verkhovna Rada of V and VI convocations recently published photos taken inside of an Odessa pretrial detention center showing utterly unsanitary and appalling conditions. Zhuravko noted, “I am shocked at what was seen. It is a concentration camp. It is a hotbed of diseases.”

Another Ukrainian journalist, Pavel Volkov, was subjected to the same types of accusations lobbed against Vyshinsky. Volkov spent over a year in the same pretrial detention center as Vyshinsky. He was arrested on September 27, 2017, after Ukrainian authorities carried out searches of his wife and mother’s apartments without the presence of his lawyer and with what he says, was a false witness.

Volkov spent more than a year in a pretrial detention center on charges of “infringing on territorial integrity with a group of people” and “miscellaneous accessory to terrorism.” On March 27, 2019, he was fully acquitted by a Ukrainian court.

Volkov shared his thoughts on the persecution of journalists in Ukraine, saying:

The leaders of the 2014 Euromaidan movement, who subsequently occupied the largest positions in the country’s leadership, repeatedly stated that collaborators from World War II who participated in the mass extermination of Jews, Russians, and Poles are true heroes in Ukraine, and that the Russian and Russian-speaking population of Ukraine are inferior people who need to be either forcibly re-educated or destroyed.

They also believe that anyone who wants peace with the Russian Federation, and who believes that the Russian language (the native language for over sixty percent of Ukraine’s population) should be the second state language, is the enemy of Ukraine.

These notions formed the basis of the new criminal law, designed to persecute politicians, public figures, journalists, and ordinary citizens who disagree with the above.

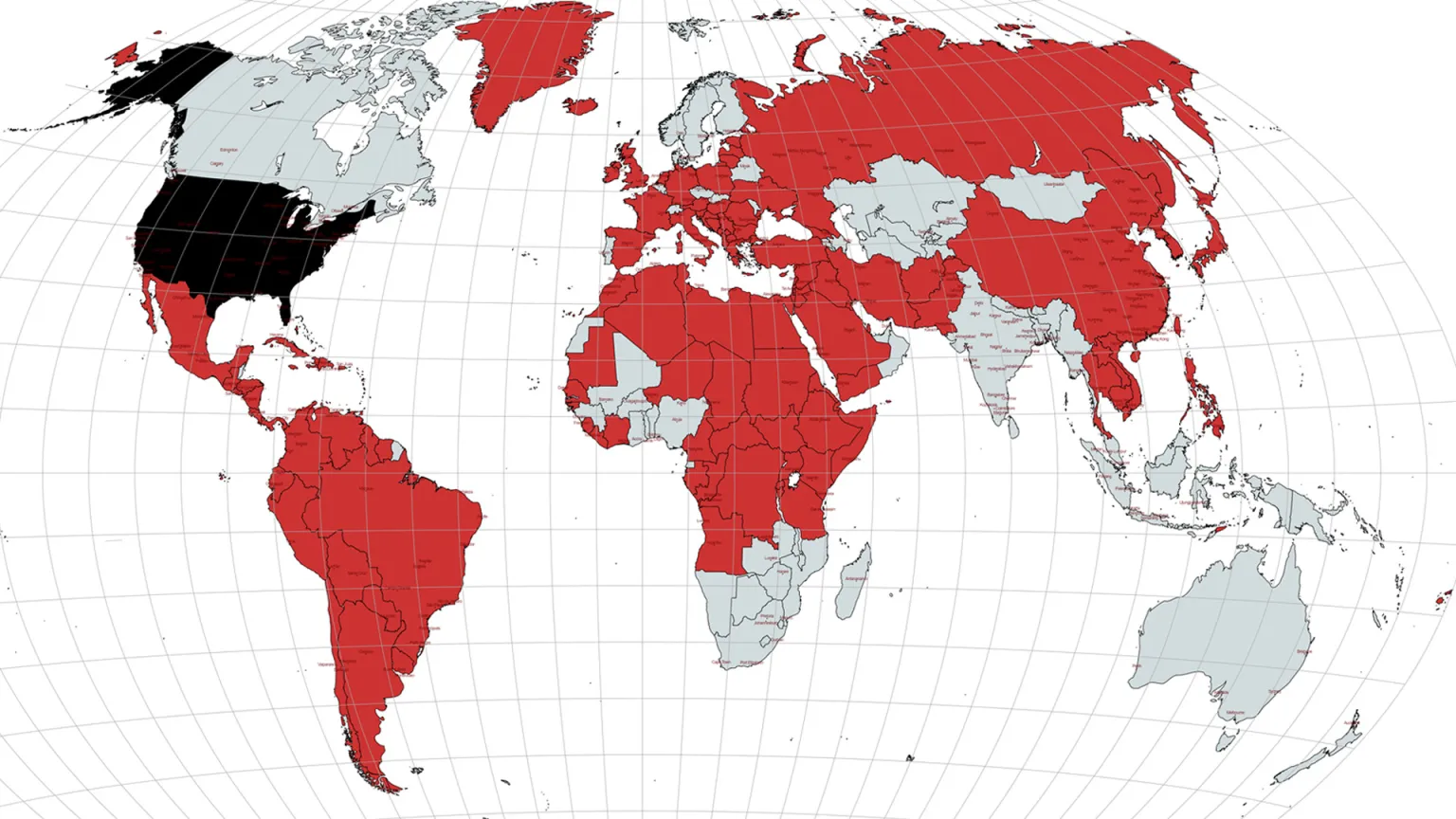

Since 2014, security services have arrested hundreds of people on charges of state treason; infringing on the territorial integrity of Ukraine; and assisting terrorism for criticizing the current government in the streets or on the Internet.

People have been in prison for years without a conviction. And these are not only the journalists included in the ‘Vyshinsky list’.

Activists from Odessa, Sergey Dolzhenkov and Evgeny Mefedov, have spent more than five years in jail just for laying flowers at a memorial to the liberators of Nikolaev [Ukrainian city] from Nazi invaders.

Sergeyev and Gorban, taxi drivers, have spent two and a half years in a pretrial detention center because they transported pensioners from Donetsk to Ukraine-controlled territory so that they could receive their legal pension.

The entrepreneur Andrey Tatarintsev has spent two years in prison for providing humanitarian assistance to a children’s hospital in the territory of the Lugansk region not controlled by Ukraine.

Farmer Nikolay Butrimenko received eight years of imprisonment for paying tax to the Donetsk People’s Republic for his land located in that territory.

The 85-year-old scientist and engineer Mekhti Logunov was given twelve years because he agreed to build a waste recycling plant with Russian investors. The list is endless.

People often incriminate themselves while being tortured or under the threat of their relatives being punished, and such confessions are accepted by the courts, despite the fact that lawyers initiate criminal proceedings against the security services involved in the torture. These cases are not being investigated.

The only mitigation that has happened in this direction after the change of government was the abolition of the provision of the Criminal Procedure Code stating that no other measure of restraint other than detention can be applied to persons suspected of committing crimes against the state.

This allowed some defendants to leave prison on bail, but not a single politically-motivated case has yet been closed. Moreover, arrests are ongoing.

The only acquittal to date from the so-called journalistic cases on freedom of speech is mine. However, it is still being contested by the prosecutor’s office in the Supreme Court.

Ninety-nine percent of the media continue to call all these people ‘terrorists’, ‘separatists’, and ‘enemies of the people’, even though almost none of them have yet received a verdict in court.”

Volkov’s words lay bare the true nature of the allegations made against Kirill Vyshinsky as well as the countless other journalists and citizens of Ukraine that have fallen victim to the heavy hand of Ukrainian authorities.

Eva Bartlett is a Canadian independent journalist and activist. She has spent years on the ground covering conflict zones in West Asia, especially in Syria and occupied Palestine, where she lived for nearly four years. She is a recipient of the 2017 International Journalism Award for International Reporting, granted by the Mexican Journalists’ Press Club (founded in 1951), was the first recipient of the Serena Shim Award for Uncompromised Integrity in Journalism, and was short-listed in 2017 for the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism. See her extended bio on her blog, In Gaza.