Russell “Texas” Bentley returned to The Grayzone alongside regular Toward Freedom contributor Fergie Chambers to detail their experiences documenting the war in the Donbass region. Chambers discussed his recent visit to a dungeon of the Ukrainian state-backed Aidar Battalion, and his interviews with Donetsk-based communists, while Texas described being on the front lines with the Donetsk People’s Republic militia.

Related Articles

Related Articles

Accused of Treason and Imprisoned Without Trial: Journalist Kirill Vyshinsky Recounts His Harrowing Time In a Ukrainian Prison

Editor’s Note: The following report and the above video were originally published by MintPress News.

In November 2018, I became aware of the case of Kirill Vyshinsky, a Ukrainian-Russian journalist and editor imprisoned in Ukraine without trial since May 2018, accused of high treason.

Soon after, I interviewed Vyshinsky via email. He described his arrest and the accusations against him as politically-motivated, “an attempt by the Ukrainian authorities to bolster the declining popularity of [then] President [Petro] Poroshenko in this election year.”

Vyshinsky noted that his arrest was advancing the incessant anti-Russian hysteria now prevalent among Ukrainian authorities, as he holds dual Ukrainian and Russian citizenship. He noted that the charges against him, which pertain to a number of articles he published in 2014 (none of them authored by Vyshinsky), became of interest to Ukrainian authorities and intelligence services four years after they were published. To Vyshinsky, this supports the notion that neither the articles nor their editor were a security threat to Ukraine, instead, he says, they were a political card to be played.

In early 2019, I traveled to Kiev to interview Vyshinsky’s defense lawyer Andriy Domansky about the logistic obstacles of his client’s case. Domansky viewed the Vyshinsky case as politically motivated and expressed concern that he could himself become a target of Ukraine’s secret service for his role in defending his client, an innocent man.

Domansky told me at the time:

The Vyshinsky case is key in demonstrating the presence of political persecution of journalists in Ukraine. As a legal expert, I believe justice is still possible in Ukraine and I will do everything possible to prove Kirill Vyshinsky’s innocence.”

To the surprise of those following the case against Vyshinsky, in late August 2019 he was released with little fanfare after serving more than 400 days in a Ukrainian prison but still faces all of the charges brought against him by the Ukrainian government and is “obliged to appear in court or give testimony to investigators if they deemed it necessary.”

By early September, Kirill Vyshinsky was on a plane to Moscow. Despite never being tried or officially convicted, he found himself the subject of a prisoner exchange between the Russian and Ukrainian governments.

I interviewed Vyshinsky in Moscow in late September. He told me about his harrowing ordeal, the Ukrainian detention system, other persecuted journalists, and what lies ahead for him.

He also touched on the inhumane conditions he experienced in Ukrainian prisons. He noted that a pretrial detention center as we know it in Western nations is a very different entity in Ukraine and that Ukrainian prisons were so over-crowded that it was common for inmates to sleep in three shifts in order to allow enough standing room for inmates crammed into a cell.

Ukrainian Prisons Like a ‘Concentration Camp’

Aleksey Zhuravko, a Ukrainian deputy of the Verkhovna Rada of V and VI convocations recently published photos taken inside of an Odessa pretrial detention center showing utterly unsanitary and appalling conditions. Zhuravko noted, “I am shocked at what was seen. It is a concentration camp. It is a hotbed of diseases.”

Another Ukrainian journalist, Pavel Volkov, was subjected to the same types of accusations lobbed against Vyshinsky. Volkov spent over a year in the same pretrial detention center as Vyshinsky. He was arrested on September 27, 2017, after Ukrainian authorities carried out searches of his wife and mother’s apartments without the presence of his lawyer and with what he says, was a false witness.

Volkov spent more than a year in a pretrial detention center on charges of “infringing on territorial integrity with a group of people” and “miscellaneous accessory to terrorism.” On March 27, 2019, he was fully acquitted by a Ukrainian court.

Volkov shared his thoughts on the persecution of journalists in Ukraine, saying:

The leaders of the 2014 Euromaidan movement, who subsequently occupied the largest positions in the country’s leadership, repeatedly stated that collaborators from World War II who participated in the mass extermination of Jews, Russians, and Poles are true heroes in Ukraine, and that the Russian and Russian-speaking population of Ukraine are inferior people who need to be either forcibly re-educated or destroyed.

They also believe that anyone who wants peace with the Russian Federation, and who believes that the Russian language (the native language for over sixty percent of Ukraine’s population) should be the second state language, is the enemy of Ukraine.

These notions formed the basis of the new criminal law, designed to persecute politicians, public figures, journalists, and ordinary citizens who disagree with the above.

Since 2014, security services have arrested hundreds of people on charges of state treason; infringing on the territorial integrity of Ukraine; and assisting terrorism for criticizing the current government in the streets or on the Internet.

People have been in prison for years without a conviction. And these are not only the journalists included in the ‘Vyshinsky list’.

Activists from Odessa, Sergey Dolzhenkov and Evgeny Mefedov, have spent more than five years in jail just for laying flowers at a memorial to the liberators of Nikolaev [Ukrainian city] from Nazi invaders.

Sergeyev and Gorban, taxi drivers, have spent two and a half years in a pretrial detention center because they transported pensioners from Donetsk to Ukraine-controlled territory so that they could receive their legal pension.

The entrepreneur Andrey Tatarintsev has spent two years in prison for providing humanitarian assistance to a children’s hospital in the territory of the Lugansk region not controlled by Ukraine.

Farmer Nikolay Butrimenko received eight years of imprisonment for paying tax to the Donetsk People’s Republic for his land located in that territory.

The 85-year-old scientist and engineer Mekhti Logunov was given twelve years because he agreed to build a waste recycling plant with Russian investors. The list is endless.

People often incriminate themselves while being tortured or under the threat of their relatives being punished, and such confessions are accepted by the courts, despite the fact that lawyers initiate criminal proceedings against the security services involved in the torture. These cases are not being investigated.

The only mitigation that has happened in this direction after the change of government was the abolition of the provision of the Criminal Procedure Code stating that no other measure of restraint other than detention can be applied to persons suspected of committing crimes against the state.

This allowed some defendants to leave prison on bail, but not a single politically-motivated case has yet been closed. Moreover, arrests are ongoing.

The only acquittal to date from the so-called journalistic cases on freedom of speech is mine. However, it is still being contested by the prosecutor’s office in the Supreme Court.

Ninety-nine percent of the media continue to call all these people ‘terrorists’, ‘separatists’, and ‘enemies of the people’, even though almost none of them have yet received a verdict in court.”

Volkov’s words lay bare the true nature of the allegations made against Kirill Vyshinsky as well as the countless other journalists and citizens of Ukraine that have fallen victim to the heavy hand of Ukrainian authorities.

Eva Bartlett is a Canadian independent journalist and activist. She has spent years on the ground covering conflict zones in West Asia, especially in Syria and occupied Palestine, where she lived for nearly four years. She is a recipient of the 2017 International Journalism Award for International Reporting, granted by the Mexican Journalists’ Press Club (founded in 1951), was the first recipient of the Serena Shim Award for Uncompromised Integrity in Journalism, and was short-listed in 2017 for the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism. See her extended bio on her blog, In Gaza.

ANC Secretary-General Says Putin Welcome In South Africa Despite ICC Arrest Warrant

ANC: PUTIN WELCOME

South Africa wants peace between Ukraine and Russia. That was the message from the head of the country’s ruling ANC party, during a feisty interview with the BBC. Fikile Mbalula also stressed his party would welcome the Russian President if he attended the… pic.twitter.com/prUckb7xI6

— African Stream (@african_stream) May 27, 2023

South Africa wants peace between Ukraine and Russia. That was the message from the head of the country’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) party during a contentious interview with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Fikile Mbalula also stressed his party would welcome Russian President Vladimir Putin if he attended the upcoming BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) summit in Durban, South Africa. That’s despite the International Criminal Court issuing an arrest warrant for Putin over alleged war crimes in Ukraine. Digital news outlet African Stream breaks it down.

‘Only Complete Military Defeat of Ukraine Is Resolution’: Q&A with Russian Communist Leader on Ukraine, Russia, China & More

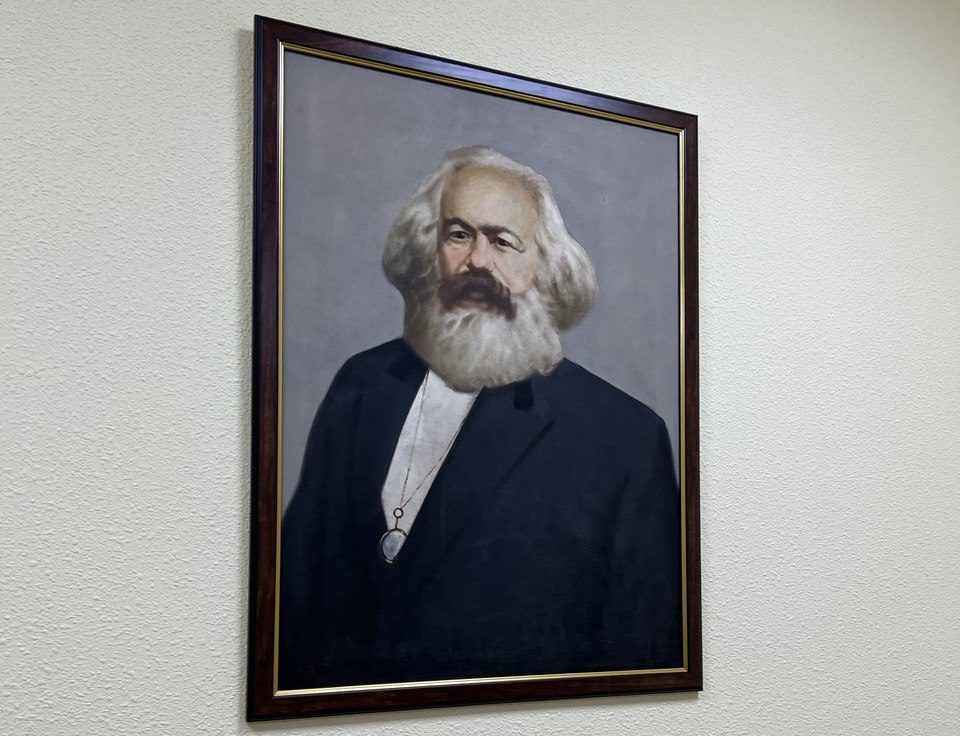

TF contributor Fergie Chambers got the opportunity on April 15 to conduct an in-person interview in Saint Petersburg, Russia, with Roman Kononenko, a member of the Presidium of the Central Committee of Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) and First Secretary of the Saint Petersburg City Committee of the KPRF. The interview ranged on topics including, the Russian “special military operation,” the nature of the Ukrainian state, the KPRF’s standing within Russia, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s popularity and China. This interview was conducted mainly in English and a little in Russian.

Fergie Chambers: Well, first off, can you tell me about the KPRF’s position on the conflict in Ukraine?

Roman Kononenko: From the very first day, we issued a statement in support of the special operation, and we also use this word, “special operation.”

FC: As opposed to war, invasion or incursion…

RK: Yes, we do not use neither war, nor invasion, nor interference. We called it “special operation,” as soon as it was put in Russia’s official documents. So we deeply believe that the current Ukrainian state is not self-governed, is not independent. It is completely controlled by the so called “collective West.” I mean, the European Union, U.S. and NATO. So we believe that the Ukrainian government is a puppet government and puppet, that they do not actually pursue their national interests in what they are doing. And of course, another reason is this unbelievable growth of Nazism, of fascism. We can discuss whether we should call it fascism or Nazism, but there are definitely Ukrainian Nazis. And many efforts were made by the West during the last eight years to support it. They were investing money, through the Western NGOs, for this, officially under the pretext of building national identity. But actually, this was Nazism. And even now, for example, in the town of Melitopol or in Berdyansk, the Russian military have found books, leaflets, published and paid by EU authorities, and also the other NGOs from the European countries. If we study everything carefully, it is obvious that they were trying to create an image that Russia is an enemy.

FC: So when you say Russia, specifically, are we actually talking Russian people, as opposed to just the Russian government?

RK: Yes, Russian people. Everybody who speaks Russian, who comes from Russia is an enemy. He may have a nationality or be from, for example, the Republic of Buryatia or Dagestan or Chechnya, but he speaks Russian. And for them, he’s an enemy.

FC: Mm-hm.

RK: Which is, of course, a dangerous situation. So sooner or later, the situation would have obviously exploded.

FC: It was interesting, because I interviewed a man in Kishinev [Moldova] who was the head of the Ukrainian Association of Moldova, an NGO there. And I asked him about Nazism, and he said, you know, “We’re not Nazis,” like you said. He said, “We’re interested in the creation of a national identity.” And the next sentence was, “Did you know that in 2016, there were blood tests that showed that Russians have Mongol blood, and that Ukrainians have European blood?” To say, “We’re not Nazis,” and then immediately to make a comment about blood and eugenics, it’s crazy. And these are the “moderates.”

RK: And also they have visible attributes, images of belonging to the Nazi movement. You know, that’s the official slogan that they use, “Slava Ukraini” [Glory to Ukraine]. Slava is actually kind of copying the German, “Heil Hitler.” This is actually the same or what they say in the Ukraine. This is, “Ukraine over everything.”

FC: As in, “Deutschland Uber Alles” [Germany Above Everything].

RK: Yes. This is copying. They are copying what the Nazis were doing, what they were saying. They are even using the same explanations to explain why Russians are not the people of the same European blood, you know, swastikas, symbols of Azov, and images of Hitler. We have a lot of photos. We had them before the special operation started, and some of them even managed to get to the pages of Western media, but no reaction at all. And also what we have in Ukraine is that these ultra Nazis not only just exist, but they serve the Ukrainian government. They are part of the Ukrainian special forces. They are part of the Ukrainian army. All of them have military ranks. So, former Nazi paramilitary groups became parts of either the National Guard, or the armed forces of Ukraine. And this is another example that the Ukrainian state uses open Nazis: Either uses them, or serves them. That can also be discussed.

FC: And what about the position of the international “left,” or other “left” parties in Russia?

RK: So as to the position of the left. In terms of this military operation, of course, we have different viewpoints. I have not analyzed what the socialist parties are saying. I have not analyzed what some small leftist groups are saying.

FC: You mean in Russia or elsewhere?

RK: I mean the West. We are just reading what the European communist parties are saying about this, this operation and the whole situation. All of them have denounced “Russian invasion,” and all of them are saying that it’s an imperialist war. [Within the context of capitalism, imperialism involves using military force to protect the capital produced through the exploitation of land, labor and resources after that capital circulates outside the countries inside of which the capital had accumulated.] I can name you only one party which published a statement in support of what Russia is doing. It’s a Serbian party, the new Communist Party of Yugoslavia. I think they are just using the older Marxist-Leninist instruments to analyze the situation. [Marxism-Leninism is the communist ideology that emphasizes building a revolution through the development of a small group of people who dedicate their time to organizing the masses, as opposed to a mass-based party, in which decisions may be made in a more deliberate fashion.]

FC: Explain more?

RK: If you read [Bolshevik leader Vladimir] Lenin’s Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, and if you read and understand everything literally, then, okay, you could argue that this is an imperialist war. But Lenin always taught us to analyze each situation, taking into account, into consideration, the current situation, the current historical situation and stuff. So, if we take all of the other aspects: Of course, maybe Russia has some of its own imperialist interests. For example, we can take Syria as an example. I don’t believe that Russia wanted to protect Syrian people from what was happening from Daesh, from occupation. Russia was following its interest in Syria. But, had it not been for the Russian interference in Syria, I think today we would not have had any independent, sovereign Syrian state. So we can say that such kind of interference that we that we faced in Syria was of [a] progressive character.

FC: I’ve heard people argue that even in the sense of Lenin’s definition, that Russia does not qualify as an “imperialist state” in the same capacity as the West, because of the lack of finance capital and export capital in Russia. I’m wondering what you think about that?

RK: Yeah, that’s true. That’s true. Russia didn’t export a lot of capital, and I think almost the majority of Russian capital, which was exported, it was to Ukraine, and a lot of it was lost in 2014.

FC: What do you think about these allegations that are coming out about Mariupol, Bucha. You know, every day, there’s a new thing: Azov making a statement that chemical weapons were used…

RK: We can see that this Bucha case is a provocation. It never happened, what we saw on Western TV and Ukrainian TV. This was completely staged by the Ukrainian armed forces, and political technologists, because we know that Russian forces left Bucha on the 30th of March. We saw public celebrations in Ukrainian media that, said, “Okay, now we are here in ‘Liberated Bucha,'” and there was no mention about any kind of massacre. Then there were publications in Ukrainian social media that they were starting a “cleanup” of the territory. And only after the Ukrainian “cleanup,” we saw what we now see in the pictures. So, I think they were just peaceful people, who were killed by Ukrainian armed forces or other nationalist paramilitary groups. Because if we look at the pictures or the photos and videos attentively, we can see white armbands. As it is happening in the Russian controlled territory of the of Ukraine, the Russian armed forces ask peaceful people just to put this white strap on the elbow. So it is obvious that, I mean, I think the Ukrainians killed those people for cooperation with Russians and whatever. As to Mariupol, and other cases, now we can see that Ukrainian armed forces are using, in fact, terrorist tactics. As it was happening in Syria, for example, they are using the peaceful population as a live shield. This makes no sense, because, if we take, for example, the war against Nazi Germany, how was the Army reacting? They were building protective lines in front of the city, trying not to let the enemy army to enter the city. Now they get inside the city, among the buildings, on the roofs, in the apartments. And they don’t let the peaceful population leave the city. They want to get a picture of destruction, devastation, and they want to say that many peaceful people were killed. These are terrorist tactics. This is not classical warfare.

FC: Mm-hm.

RK: The Army’s using its own people to create an image of the crimes they are committing.

FC: So, another thing that seems to really fluctuate every day in the Western media is how the actual battle is going. One day, we see the Ukrainians are “humiliating Putin.” The next, that the “brutal Russian army” is laying waste to Ukraine. How do you see it?

RK: We have a saying, that an almost destroyed enemy begins their cowardly onslaught. Of course, here we are. We don’t know everything. Sure, how the decisions were made, and why, we ask a lot of questions. But I don’t have a full military education. I studied in university at the military faculty. This is like, one day a week, you go to study, and then you become a lieutenant. But I’m not a military expert. What happened when they decided to leave the Kiev and Chernihiv region? I still don’t understand. We lost the lives of our soldiers. There were people who were welcoming the Russian army, and suddenly, we left, and we left those people to the Ukrainians who came and then the Bucha affair happened.

FC: So, from your position, you don’t understand the decision to abandon the North?

RK: I cannot understand this.

FC: The only theories I’d heard about that is just that, you know, the idea was to decentralize the Ukrainian forces, which might have been concentrated in Donbass.

RK: Yeah. But to tie them up for some periods in Kiev or Chernihiv, but now they are free to go back to Donbass. It’s strange.

FC: Yes, strange. So tell me, maybe more broadly, what do you think were the primary factors that played into this having to be resolved in a military way, as opposed to being resolved diplomatically? For instance, why didn’t the Minsk agreements work out? Or what forces do you think were most at play in their failure?

RK: I think the agreements didn’t work out because the Ukrainian government was never going to implement them. In seven years, they hadn’t even made a single step toward implementing them. And, from time to time, you would hear high-ranking Ukrainian officials boasting that they are not going to fulfill anything, oficially, openly on TV and media.

FC: Right.

RK: And also, according to the results of what our armed forces found there after the operation started, we could see that they found plans: Military maps and plans of invasion into Donbass and into Crimea. These documents were shown all over our media and social media. Of course, I think that our government had some intelligence information before, because, you know, the military way of solving issues is the last the way you should be using. I think they had some kind of information, which made them think and believe that the only way to solve this was militarily.

FC: And that a larger invasion of the East might be coming in Donbass. And what do you see as the best possible resolution to the conflict at this moment?

RK: I think in the current stage of the conflict, only complete military defeat of Ukraine can be a resolution of this conflict, because even if they sign any kind of truce or peaceful agreement, nothing would end. Looks [like] we have an entire Russian border with an anti-Russian population. I think even if we would sign a peaceful agreement, and leave everything as it is, nothing would end. The shelling of Russian territories would be continued as they happened for years already, and yeah, yesterday they attacked the Belgorod region, the Kursk region and the Bryansk region. We need to put an end to this. Unfortunately, at this current stage, this is the only solution.

FC: When you say complete military defeat, does that imply, a partition of Donbass, as well? And does it also imply the end of Euromaidan [right-wing protest movement]? Does it imply a change of the Kiev government entirely?

RK: Complete capitulation of the Kiev government, and a new government should come. I think there must be some provisional government. Of course, the new government should be democratically elected, but under new conditions, not under control of fascist forces.

FC: How do you think that these kinds of nationalist conflicts arose so strongly after the fall of the USSR?

RK: I really do not know because I do not live there. But I think that, of course, it took them many years to build this so-called national identity. I am stretching “so-called.” A lot was made in this piece of culture in Ukraine, in the spheres of “studying history.” You know, they were creating a complete fake history of an ancient Ukrainian state, which never existed.

FC: Fake, as distinct from Kiev/Rus?

RK: Yeah. There are a lot of crazy theories there. Some even said that Ukrainians dug the Black Sea. This kind of stuff was being spread everywhere, for many, many years. To show that the Ukrainian nation is something exquisite.

FC: What was your relationship like as a party with Ukrainian socialist or communist parties?

RK: Oh, we had very good relations and we still have with the Communist Party of Ukraine.

FC: And what is their situation? I mean, they’re illegal, no?

RK: They are illegal. Many comrades were arrested during the last years. They were always attacked, regularly beaten in the streets by the fascist thugs. Currently, we don’t know where the leader of the Communist Party of Ukraine is.

FC: Because he was detained, or because he hid? What’s his name?

RK: [Petro] Symonenko. We don’t know which [detained or hiding]. Since February, the 24th, we don’t have any news on where he is. But also, for example, the leader of the Youth Organization of the Communist Party of Ukraine was arrested.

FC: And what was [the Communist Party of Ukraine’s] political position, prior to Maidan? How strong of a party were they?

RK: The party was quite strong, the second or the third faction in the Ukrainian parliament, with many members. But after the coup, they became illegal. It’s kind of ridiculous, because there was a decision of the Ministry of Justice to ban the party. They went to court, and the trial is still going on. So, in fact, the decision has never been made official, to ban the Communist Party of Ukraine. But in fact, all Ukrainian authorities and governmental bodies consider it like a decision, which is already in power.

FC: So they enforce it?

RK: Yes.

FC: What’s the relationship like between KPRF and smaller socialist parties in Russia? Is there a good working relationship with any of the other parties? Is there any kind of a left bloc or is it more scattered?

RK: There is no bloc. Can you name me any smaller socialist parties?

FC: No.

RK: Me neither. We have this party that is called Fair Liberals. They are saying they’re social democrats, but they are not, neither in ideology, nor in their practical steps. We never noticed them, so we don’t even identify them as belonging to socialism. But they were members of the Socialist International.

FC: Some Western leftists, and Russian radicals, would accuse KPRF of being a revisionist party, or dismiss it as a relic of the past, a party of only the elderly. What would you say about the position of the party today? [Revisionism refers to a policy of making modifications without adhering to revolutionary principles.]

RK: We are the second [largest] party in the Parliament. We are the biggest opposition party. As to the accusations of being revisionist, we put it into our program that we use the “creative development of Marxism-Leninism,” because Marxism-Leninism is not a dogma. But of course, think I’m not a revisionist. I cannot admit that I’m revisionist. I will never be revisionist. (Laughs) I have been a party member for 21 years already, and I am relatively young.

FC: How old are you?

RK: I’m 40. It’s not a party of old people. Of course, we have many old party members who were members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). But those people who vote for our party are not the people of that age. We are supported mostly by people between [ages] 30 and 50. And the elderly, they vote for Putin’s party.

FC: How has the Party attempted to reach a post-Soviet generation?

RK: We’re just addressing the common problems, because the problems of both younger generations and other generations are very common in Russia. We are talking about social problems and we are proposing our methods to fix the situation. Our measures.

FC: For instance, what are the primary social contradictions at play in Russia from the perspective of the KPRF?

RK: Russia is a capitalist country, yes, with much of its wealth controlled by the oligarchs. We believe that our natural resources should be nationalized, not on paper as they are now. But, in fact should be nationalized and serve the development of our industry, the development of our economy, the development of our, and this is a fashionable term, “human capital.”

FC: In the West, we have heard about some recent nationalization of the Russian economy. When you say it’s “on paper,” what do you mean by that?

RK: For example, oil and gas, in the constitution, it is written there that they belong to the people. But, in fact, those who exploit it are private companies; they simply pay extra taxes, but they take the profits. For example, Gazprom, the biggest gas producing company, is a private company. You know, the several years ago, they put a big campaign on Russian TV saying, “Gazprom is a national heritage.” But this national heritage is a private company. Of course, there is some state participation in its ownership, but it doesn’t even have a controlling share.

FC: But [the state] does have some interest. So it’s different than the way it would operate in the purely capitalist West?

RK: Yes, to some extent.

FC: And when you mentioned, social problems, is that what you’re talking about?

RK: No. Okay. We’ve always had a lot of problems, and these problems have not disappeared since the start of the military operation. There is a big gap between the incomes of the poorest and the richest, which sometimes comes to 30 times different. This is a huge gap. And another thing was the so called “pension reform,” which happened in 2018, when they increased the retirement age. The government did this.

FC: Did you see a spike in popularity around that issue?

RK: In popularity, in support? Yeah, of course. We didn’t have a federal election that year, but we had regional elections, and we seriously improved our results; we received two new governors of the oblasts [regions].

FC: How many governors of the oblasts do you have currently ?

RK: Currently, three.

FC: And seats in parliament?

RK: I don’t remember exactly. Ninety plus.

FC: What’s the rough percentage?

RK: I think 19 percent. But this is second to United Russia, because United Russia controls the state.

FC: And speaking about United Russia, from my perspective, I’m probably more sympathetic to United Russia, from the dialectical lens of an American, than I might be if I was here in Russia. You talk about income, the income gap, you talk about nationalization of resources, you talk about oligarchy. It seems just looking in from the West, that these are problems that the West would like to blame on Putin. But it looks like they’re all things that have improved significantly in the last 20 years, versus the way they were in the ’90s. Would you agree with that? Not that they’ve resolved themselves, but that the material conditions for the masses in Russia have improved under Putin, versus [in] the ’90s?

RK: Of course, but they improved mostly between the years 2000 and 2011, because of the high oil and gas prices in those years. And we call them “fat.”

FC: Like a bubble?

RK: Yes, and we’re still facing many issues that are unsolved, and all of these were made by United Russia. We have a lot of problems in the health care system, because during all these years, they were following one general line of so called “optimization.” They were closing hospitals and clinics, to create one instead of two, like to optimize, not to spend a lot of money. And closing some small group hospitals.

FC: In the name of efficiency?

RK: Efficiency, yeah. And, of course, everything exploded when COVID-19 appeared, because, suddenly, it turned out that in many hospitals or regional centers, the infection departments were closed, or “optimized.” So they didn’t even have medical facilities to isolate people, and they had to take them to neighboring regions. Of course, they had to do something very quickly, and they had to create some new facilities. But what happened in the beginning of 2020—in March and April—was that we didn’t have enough [beds] in the hospitals for those who were infected with COVID.

FC: I didn’t know about that. Tell, me, it’s my belief that the “human rights” issue is often a tool of imperialist propaganda, but is the party concerned about human-rights issues in Russia—or civil rights—with regard to United Russia? Do you feel like state repression is an issue?

RK: Yes, we are concerned. I think civil rights are something important. But they are not less important than social rights, right? Than rights for social protection. But when United Russia is attacking, for example, a civil democratic right for people to come out in the street to protest, we are against this attack. We want to protect this.

FC: So you’re against the detention of protesters?

RK: Yes. We are among those who come out in the streets to protest against them, [and] other anti-people measures of United Russia.

FC: Not to protest the special operation in this moment, but other issues?

RK: Yes. But we know many cases of persecution, and persecution is not legal, even according to their laws.

FC: So this kind of persecution for either protests or journalism, around the special operation or other issues, does it usually look like actual hard jail time, or does it usually look like fines?

RK: Almost exclusively fines. None of our members [were] ever sent to jail because of some political activity. I really don’t think.

FC: Because, in the West, there’s this notion that if you step out of line in Russia, Putin’s going to lock you up.

RK: Basically, no. Most probably, you will be arrested, you will spend the night in a police station. Maybe [the] next day, they will take you to court and fine you. That’s the most common outcome.

FC: The other thing, in the West, we never hear about about the Communist Party being the largest opposition. We hear about [Russia of the Future party leader Alexei] Navalny.

RK: Navalny and his supporters, they exist in small numbers, in Saint Petersburg, in Moscow, the two richest and most European cities. And then they do not present any kind of force elsewhere in Russia.

FC: This is something that I’ve noticed, that there’s a big distinction between the Russian voices that the West wants to highlight. The people you hear from in the West represent a small sliver of the Saint Petersburg and Moscow bourgeoisie, who are probably Western educated, who probably have investments in business dealings with the West, you know, and they may live there or be expatriates. Is this accurate?

RK: You’re completely, absolutely right.

FC: And so that, and that contingency, is also kind of representative of this Navalny tendency?

RK: They are the only supporters of Navalny, and they’re mostly young people, those between 16 and, maybe, 20. Why? Primarily, I don’t know why, but they want to say that they belong to some something, which they call a “creative class.” I really don’t know what it is, but they say it exists.

FC: So we see this in the U.S., really going back to the 1960s and ’70s, how youth counterculture became a really big staging ground for CIA activity, even the proliferation of anarchism. And then here, [media outlet] Vice started to come in and report on Russia a lot, and [Russian feminist band] Pussy Riot started showing up everywhere, like a symbol of Russian resistance. Does that fit?

RK: Absolutely.

FC: What’s the relationship of the party to the Communist Party of China (CPC)?

RK: We have quite close contacts. We have [a] cooperation agreement. We sign it every five years, to extend it for five years. We exchange delegations on a regular basis, and we have cooperation in the scientific aspects of studying Marxism-Leninism, as well. So we are quite closely connected.

FC: So maybe more closely connected with the CPC now than the CPSU was to the CPC was after the [1960 ideological] split?

RK: Yes, we are more closely connected. Of course.

FC: And do you see generally see a Russian-Chinese partnership as an important part of sort of historical progress moving forward?

RK: Of course. It’s a part of the historical process. It can give the world an opportunity to diversify the economy.

FC: Is the goal of the KPRF to re-take power in Russia, and to re-establish a dictatorship of the proletariat?

RK: Re-take power? Yes. But we’re not writing about dictatorship of the proletariat, in our official program. We officially put it as “building renewed socialism of the 21st century.” That’s how we call it, trying to take the best of the Soviet period, and trying to take whatever is good now.

FC: So what is the difference between the Soviet period and this concept of “renewed socialism in the 21st century?”

RK: Well, I can tell you, economically, we are not completely against private property, in general. We are saying that small private businesses can exist, like, for example, a small bakery, or a barber shop, or drug store. That’s the primary difference, because, during the Soviet period, everything was state-owned. So we believe that this, that these things could initially help drive the economy, like Lenin already did in the ’20s, the so-called NEP [New Economic Policy aimed for a transition between the post-czarist period of poverty and communism that featured a “mixed” economy, which permitted small- to medium-sized private enterprises while the state controlled large enterprises, like banks, to help provide the capital necessary for the development of productive forces]. So I think we are pursuing the same goal.

FC: As a means to eventual full communism or as just an adaptation to the current times?

RK: Of course. Finally, it must be full communism. But first, you need to build a socialist state.

FC: Similar to [Chinese leader from 1978 to 1989] Deng Xiaoping?

RK: Similar. We’re not going to copy the Chinese model, but…

FC: So I’m assuming that, at this moment, you’re also not advocating for the violent seizure of the state?

RK: Yes, we are not openly advocating for this. It is put in our documents that we should come to power through elections.

FC: And do you think this is realistic? Do you think that the elections here are open?

RK: No, we don’t. They are not honest. Yeah, but we are fighting to make them more transparent, more open, honest and fair.

FC: And so how does that happen? Because if the people controlling the elections are the ones being dishonest about it, how can you push back against that?

RK: We work harder. This is the only way. To put most responsible people in Congress, to control the voting stations. Which is, of course, difficult when the whole state apparatus is against you. But we never exclude the revolutionary way of changing power. But, of course, first you need revolutionary conditions.

FC: So would you say that maybe your focus is on growing revolutionary consciousness in Russia, or reinstituting political education?

RK: Growing class consciousness. Political education, of course. Even so called “civil activism.” There are Soviet words for this. They have written their budgets. We want to form this class-conscious position in as many people as possible.

FC: And are there any kind of broad political education programs that the party is involved in in the country?

RK: Of course, in in every region, we have our own centers of schools, of political education. And, of course, we are offering our own programs here. But political education is not only just collecting people somewhere and teaching them. Political education is explaining things. Explaining, “Why this is happening and what’s the reason for this?” so education can be achieved by means of elementary leaflets, or newspapers. Or social media.

FC: And you still have Pravda?

RK: Yes, we have Pravda. This is a nationwide newspaper, and we also publish two newspapers here in Saint Petersburg.

FC: Where are some of the geographical strongholds of the party?

RK: I can’t tell you exactly, because it differs from year to year. But I think, the central parts of Russia and the Far East of Russia, Vladivostok or Khabarovsk Altai.

FC: Does does Saint Petersburg present more of a challenge because of this kind of Eurocentrism that exists here?

RK: We have many liberals, so-called liberals, in our Russian understanding. Liberals, not in the way the U.S. understands it. Many liberals here, you know, there is a liberal political party, Yabloko, which has some support in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Oh, and for example, if you come to the third biggest city in Russia, Novosibirsk, in Siberia, we have a communist mayor.

FC: Do you still consider yourselves a democratic centralist party?

RK: Yes, of course. Because without the democratic centralism, we believe that there cannot be any party discipline.

FC: Would you re-name Saint Petersburg back to Leningrad if you had the opportunity?

RK: (smiles) I don’t think this is the first thing that we have to do. I mean, sort of a joke. Maybe number 33. Yes.

FC: I’m curious about the relationship with the church, and I say this as somebody who is both a communist and Orthodox. I forget what year it was, but I read about [KPRF leader Gennady] Zyagunov and [Russian Orthodox Bishop] Kirill having a rapprochement, or a mutual acknowledgement. What’s the position of the party to the church?

RK: Party leader Gennady Zyuganov is religious. That’s his personal belief. But our party is an atheist party. We are still atheists, as a party. But we acknowledge the right of any party member to believe in God; the only demand is you should not put any religious propaganda within the party. As a person, you have a right to do whatever. And it’s written in our official documents that we are a party of scientific atheism. Not of vulgar atheism.

FC: How do you distinguish between vulgar atheism and scientific atheism?

RK: I think that there cannot be any strict definition of whether it is scientific or not scientific, but you have to fill it. It would be stupid for a communist to go out in the street and shout: “There is no God!” Right. This is vulgar, I think. But trying to explain that, so far, there has not been any proof of such existence. So that may be more scientific. But I’m personally atheist. My wife? She’s also a party member, but she believes in God. It’s okay for us.

FC: Do you think the church has too much of a role in the Russian state now?

RK: It is getting more and more involved in the society. And its role is growing. But, so far, I think it is not as almighty in the state as some people want to depict.

FC: Are there other socialist or communist parties around the world that you have especially important relationships with?

RK: We’ve always had good relations with the Communist Party of Vietnam, with the Communist Party of Cuba. Communist Party of India (CPI).

FC: The Marxist party in India?

RK: Both of them [CPI-Marxist and CPI (Maoist)] because they are different parties, but during the elections, they are part of one struggle. Really, we have international relations with all communist parties.

FC: Do you generally agree that the position of a Western communist ought to be to oppose first and foremost the imperialism of the West?

RK: I think, yes. Most of them, they are opposing imperialism, Western imperialism.

FC: Well, perhaps not in the U.S.

RK: I mean, I’m talking about the Communist Party. I’m not talking about the others, because I don’t know anything about them. Actually, I was never interested.

FC: What about Venezuela, the relationship with the Venezuelan government, with Maduro?

RK: I think we don’t have any official relations, neither with Maduro, neither with the ruling party. We have some contacts, but we cannot call it any kind of relations. Of course, we are saying that Venezuela is suffering from United States imperialism, but we also understand that not everything is okay with the Maduro government.

FC: I did mean to ask you, after the fall of the USSR, how did KPRF reorganize itself? Did it just continue on, or it had to reform itself?

RK: We, the CPSU, could not continue, because [Russian President Boris] Yeltsin banned the Communist Party in 1991. So there were special groups of former party members who worked as small groups, like, “Communists for the Soviet Union.” So then, our party went to the Constitutional Court. There was a long process, which lasted almost the whole of 1992. We tried to prove that Yeltsin’s ban was illegal, and the courts made a kind of split decision.

FC: A split decision?

RK: So it didn’t say that Yeltsin’s ban was illegal; they said it was legal to ban the Communist Party of Soviet Union, to ban the central bodies of the Communist Party of the Russian Socialist Federative Republic. But they did say it was illegal to ban the primary organizations, the grassroots organizations. So the grassroots organizations, they became legalized. I think this decision was made in the end of 1992. And in three months’ time, we organized these small grassroots organizations, and then we, in February 1993, we organized a Congress. It was called the “Extraordinary Congress of the Communist Party of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.” And, in that Congress, we created KPRF.

FC: What is the official party position on Stalin?

RK: We have never made any specific decision, or there is no written decision. We’re saying, of course, Stalin did a lot for the country, for the people. But, of course, they were violations of socialist law during this period. So that’s how we evaluate it, officially. And then internally, there are other positions, of course. There are many who would say Stalin is better than Lenin, but then a few who are anti-Stalin.

FC: But no Trotskyists?

RK: (laughs) Of course not.

FC: Who do you think was most the most destructive of the Soviet leaders, most responsible for the deterioration of the USSR?

RK: Khrushchev.

FC: Well, that says a lot. Comrade, this has been extremely interesting. Thank you so much for your time today.

RK: And thank you for coming. It is a pleasure, and you are welcome back any time.

Fergie Chambers is a freelance writer and socialist organizer from New York, reporting from eastern Europe for Toward Freedom. He can be found on Twitter, Instagram and Substack.