While the Russian “special military operation” in Ukraine turns three weeks old today, energy-rich Azerbaijan is trying to preserve good ties with both Moscow and Kyiv.

Although the situation worries the Caucasus nation snuggled along the western shores of the Caspian Sea, the Azerbaijani government—based in the capital of Baku—tends toward preserving its neutrality and it potentially benefits from exporting additional gas to Europe.

Immediate Impact of War

Two days before the invasion, Azerbaijan signed an alliance agreement with Russia. The two countries are now de facto allies, although their parliaments still have not ratified the deal. According to the document, Moscow and Baku intend to deepen cooperation in the energy sector and strengthen military ties. It is worth noting Russia is already an ally of Azerbaijan’s arch-enemy, Armenia, and the agreement Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Azeri counterpart, Ilham Aliyev, signed in Moscow on February 22 is expected to reinforce Moscow’s positions in the South Caucasus.

Still, Russia’s isolation in the international arena could have an impact on its relations with Azerbaijan. Baku already has suspended all flights to the Russian Federation, and fears have emerged that remittances the approximately 650,000 Azeris working in Russia send home will significantly decline. Moreover, Russia is Azerbaijan’s top import partner. If Moscow eventually limits exports of various goods, including food, Baku likely will have to strengthen economic and political ties with another ally, Turkey.

Double-Edged Sword

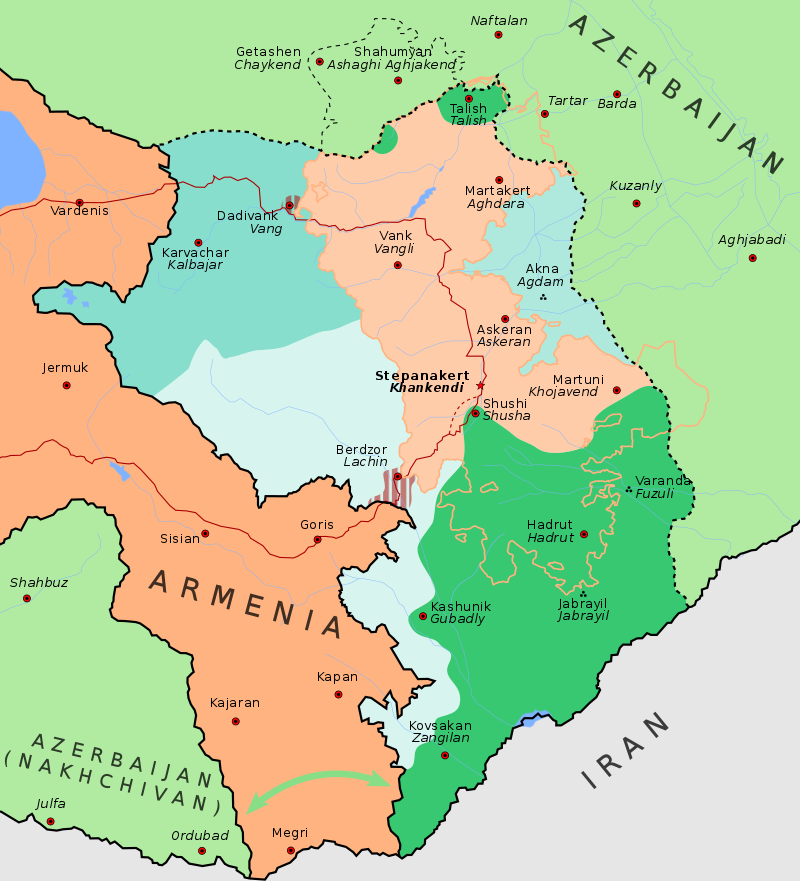

It is not a secret Ankara supplied Baku with sophisticated Bayraktar drones prior to the 44-day war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. This landlocked mountainous terrain is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, although it was under the control of Armenian forces for more than two decades. It is believed the Turkish-made weapons were a game changer in the war. As a result of the conflict, Baku restored its sovereignty over large portions of the mountainous territory, as well as surrounding areas, and some 2,000 Russian peacekeepers were deployed to the region. More importantly, Azerbaijan and Turkey became official allies, after Aliyev and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan signed in June the Shusha Declaration.

Azerbaijan is now an ally of both Russia and Turkey, which could be a double-edged sword for Baku. Although the Caucasus nation supports Ukraine’s territorial integrity, it has avoided condemning Russia’s actions or imposing sanctions on the Russian Federation.

“We have never taken decisions on imposing sanctions on any country,” Azerbaijani Deputy Foreign Minister Elnur Mammadov told Toward Freedom in an interview. He pointed out he does not expect any pressure from the West for Azerbaijan to impose sanctions on Moscow.

Fueling Demand

The European Union expects Azerbaijan to increase gas supplies to the continent, especially if Moscow eventually decides to turn off the taps. Indeed, the EU will need Azerbaijan’s energy resources to cope with possible Russian gas disruptions. But the problem is the country now does not have much more gas to export.

“In 2021, we exported 8.2 billion cubic meters of natural gas to Europe,” said Orkhan Zeynalov, the head of the International Cooperation Department of Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Energy, in an interview with Toward Freedom. “This year, we’re planning to increase the export up to 9.1 billion cubic meters.”

Such a small amount will not meet European needs for energy. In the long term, however, Azerbaijan will be able to provide more gas to Europe if it manages to increase the share of renewable energy sources for electricity production. Baku aims to turn Nagorno-Karabakh into a “green energy zone,” where foreign corporations, such as United Kingdom-based BP and United Arab Emirates-based Masdar, plan to build solar power plants. In addition, Saudi Arabian utility company Acwa Power is expected to build a 240-megawatt wind turbine farm in Azerbaijan, which should reduce the amount of gas the country currently uses.

Nakhchivan Corridor

In 2021, Azerbaijan increased its gas exports by nearly 40 percent, but the country is unlikely to ever replace Russia as Europe’s major energy supplier. Still, the growing demand for Azerbaijan’s gas will almost certainly have a positive impact on the country’s budget. Baku is expected to invest money in the construction of the Nakhchivan corridor, also known as Zangezur corridor, which seems to be a top priority for the Caucasus nation.

“We are already building 110 kilometers (68 miles) of the railway, and 124 kilometers (77 miles) of the highway in the region,” Mammadov said. “Our plan is to finish the construction by the end of 2023.”

Why is this transportation network so important for Azerbaijan? The Nakhchivan corridor will allow the energy-rich nation a land connection with its exclave, the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. At the same time, it will connect Azerbaijan with its ally, Turkey. The challenge, however, is 45 kilometers (28 miles) of the road will have to go through Armenian territory. Yerevan, unlike Baku, does not seem to be in a hurry to finish construction of the corridor, even though the railroad portion will connect Armenia with its ally, Russia, through Azerbaijan’s mainland. Yerevan, however, seems to be more interested in the construction of the North-South road corridor that will connect Armenia with Russia, through Georgia.

Georgia did not impose sanctions on Russia, even though the two nations fought a brief war in 2008. That is why the Kremlin does not see the former Soviet republic as an “enemy country,” which leaves room for normalization of relations between Moscow and Tbilisi. In the long-term, such a development would be beneficial for Armenia, given it would secure a land connection with Russia.

Although Moscow reportedly supports the project, and is actively dealing with issues on unblocking transport links in the region, it is not very probable Yerevan will complete the construction of its section of the corridor any time soon, if it all. Quite aware of that, Azerbaijan reportedly decided to bypass Armenia and connect its main territory with Nakhchivan via Iran. On March 11, Baku and Tehran signed a Memorandum of Understanding on establishing communication links in the region. Indeed, such a move could create a new geopolitical reality in the Caucasus.

But as long as the Russia-Ukraine conflict goes on, the final implementation of all the deals in the region will likely remain on hold. For the time being, both Azerbaijan and Armenia are expected to preserve good relations with Moscow, hoping the war in Ukraine will not spill over into the South Caucasus, an area the Kremlin sees at its “near abroad.”

Nikola Mikovic is a Serbia-based contributor to CGTN, Global Comment, Byline Times, Informed Comment, and World Geostrategic Insights, among other publications. He is a geopolitical analyst for KJ Reports and Enquire.