Editor’s Note: The following opinion was first published in Black Agenda Report.

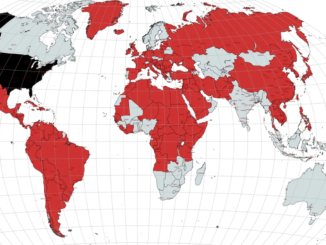

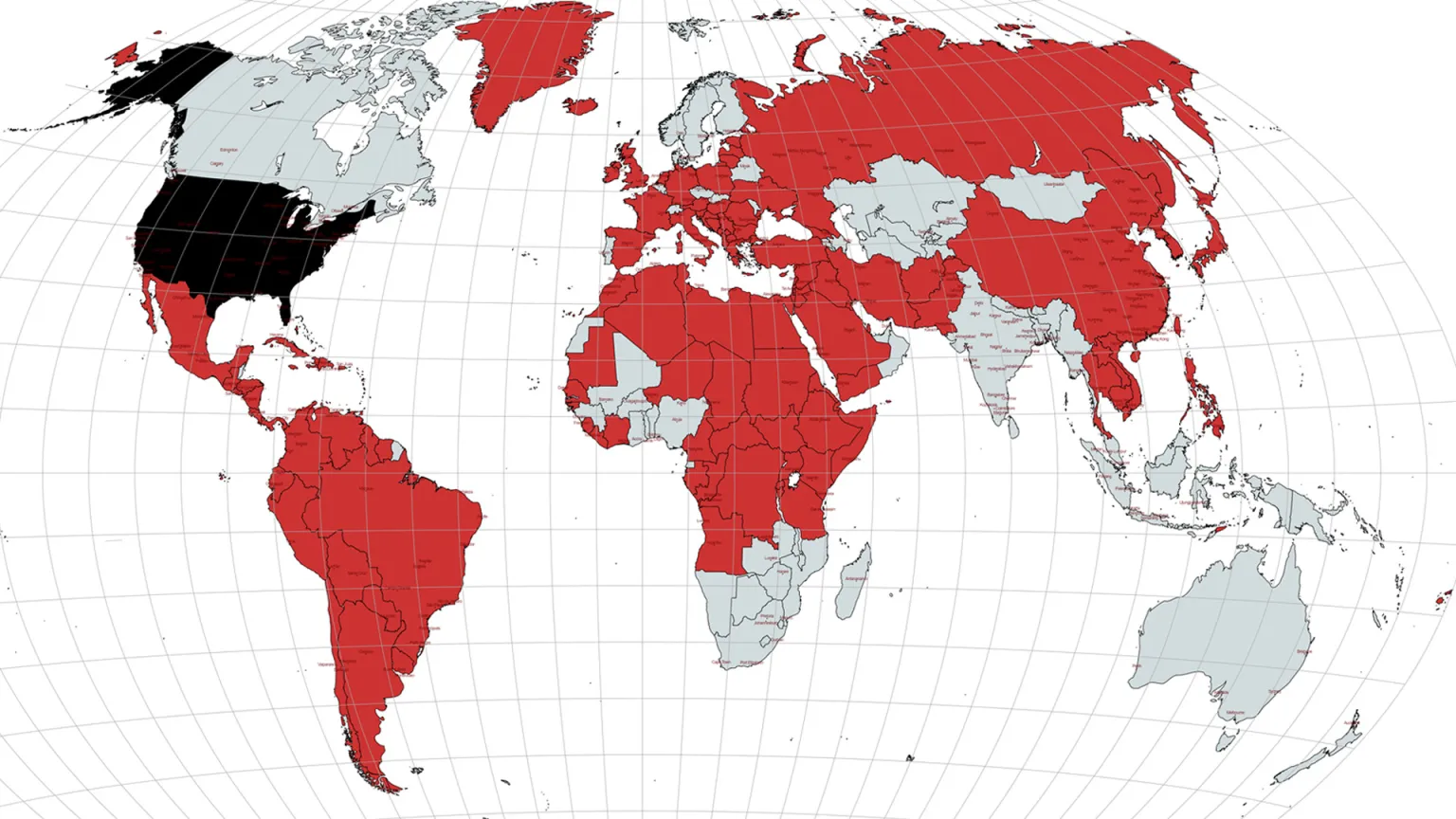

If U.S. imperialism could only be said to be one thing, it is audacious. Recently U.S. rulers have been making a fuss over Russian troops on their own border with Ukraine, while 1,000 U.S. National Guard soldiers were deployed to the Horn of Africa, in countries where the U.S. shares no borders and is actually more than 7,396 miles away.

Ever since its government was destroyed in 2011 in the first operation of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), Libya has been the quintessential victim of U.S. audacity in Africa. Now, led by the United States, Western officials have been talking up a UN-led peace process in Libya that insists on “inclusive” and “credible” elections starting on December 24, despite serious disputes over how they should be held.

Of course the Libyan people should have the right to decide their leaders, forms of government, and politics. In fact, however, it is extremely difficult to see through the murk created by the inhumanity of the U.S.-EU-NATO axis of domination.

But what sort of process for nominating candidates are the Libyan people able to exercise? How credible and inclusive can an election be that is cast in the midst of a civil war and with the United States presiding over the country’s affairs like a Godfather?

The imperialist structure responsible for leading the overthrow of the Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya , AFRICOM, just backed the election efforts of U.S. Ambassador to Libya Richard Norland. This was after Norland took to Twitter to scold those discrediting the elections saying, “We call on all parties to de-escalate tensions and to respect the Libyan-led, legal, and administrative electoral processes underway.”

For these emissaries of empire, such statements are mere words of formality, empty rhetoric meant to minimize the glare of the contradiction: they created a failed state.

Reports have surfaced about the likely re-emergence of violence which has been on pause during a very fragile ceasefire. There have been stolen voter cards , an allegedly politically motivated disqualification of 25 of the 98 presidential hopefuls by the election commission, a chaotic appeals process, and, of course, a delay in the final list of candidates.

Then there were also the road blocks by gunmen backing eastern military chief and former CIA operative Khalifa Haftar to prevent travel to a court in the southern city of Sebha set to examine the appeal by Saif al-Islam Gaddafi to run for president. It is no surprise that Haftar himself is also a presidential candidate.

Initially Saif al-Islam, son of the murdered Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, was being excluded from a bid for presidency by the High Elections Commission. Before a Libyan court ruled on December 2 that Gaddafi can run for president, the case had endured an armed attack on the Sebha Court of Appeals followed by a protest in front of the Sebha Court at the end of November, organized by the people of the city of Ghat against the closure of the court by force.

The protesters, in support of Saif Gaddafi, demanding free and fair elections, and an impartial judiciary said, “…there are those who want to occupy the country and restore colonialism again, and who threaten to divide the country according to the interests of the international powers.”

Black and Brown people of the Global South know full well about what the protesters from Ghat are protesting. The capitalist, white surpremacist order has to disparage people-centered projects and legitimize anything in the interest of racist neoliberalism.

Some of the most transparent and participatory elections in the world, in Nicaragua and Venezuela, are denounced and demonized by the same international powers, its institutional extensions like the OAS, and its corporate media mouthpieces. Beneath that newswire is the irony of a Libya literally destroyed by the same forces. Now, ten years later, it is being forced into a largely illegitimate process.

The title “dictator” is bandied around for all leaders not compliant to Western interests, as was commonly done to the late Muammar Gaddafi. A common sense question one might ask is: Why go through such lengths to prevent the candidacy of the son of a dictator supposedly intent on reestablishing his father’s dynasty?

Once the non-white working class inside the belly of the beast realize that the United States is an undemocratic oligarchy that cannot pretend to offer, to the rest of the world, a nonexistent “democracy,” then it will begin to see that the internationalist fight to support the people of Libya is the same as the domestic fight to liberate those struggling for justice.

Netfa Freeman is an organizer in Pan-African Community Action (PACA) and on the Coordinating Committee of the Black Alliance for Peace. Netfa also is co-host/producer of the WPFW radio show and podcast “Voices With Vision.”