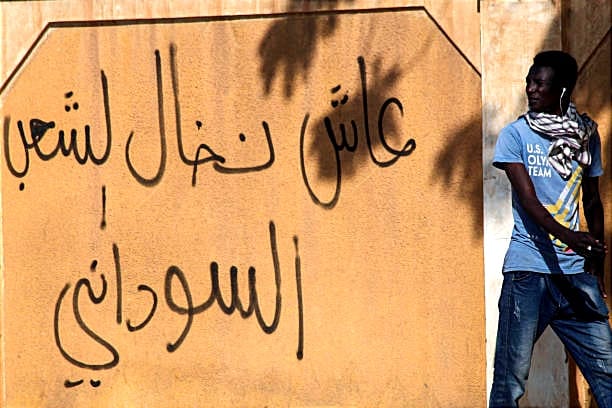

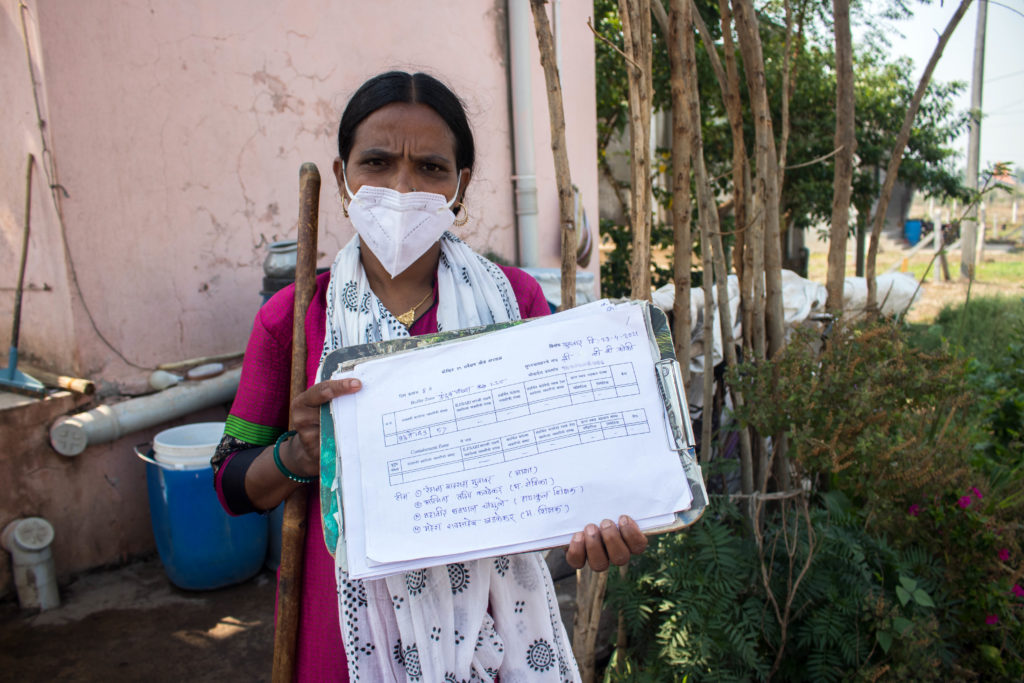

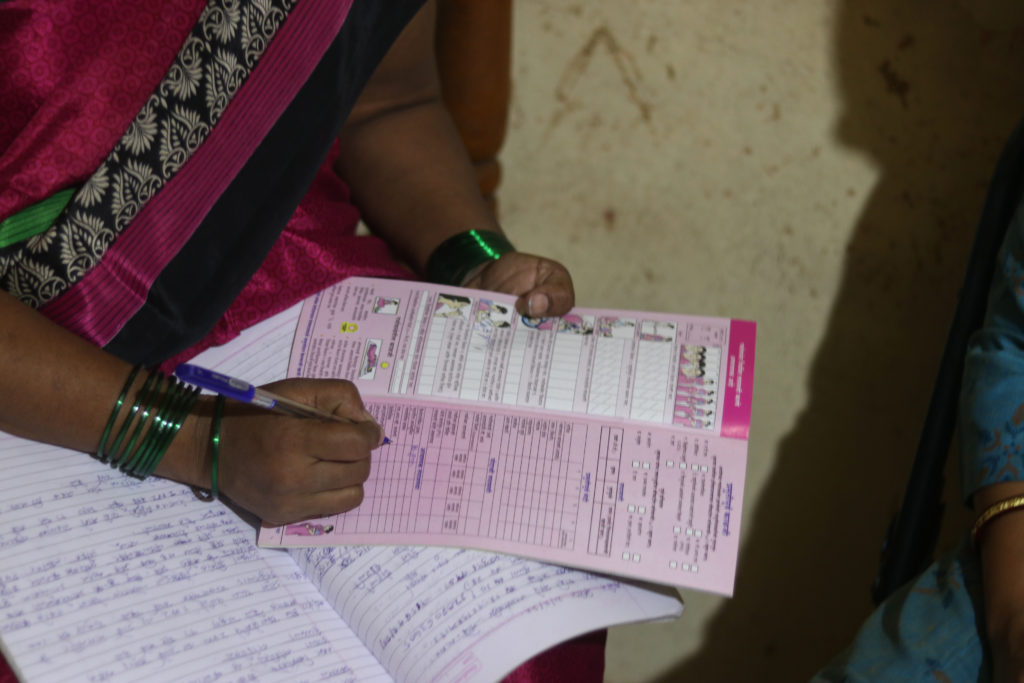

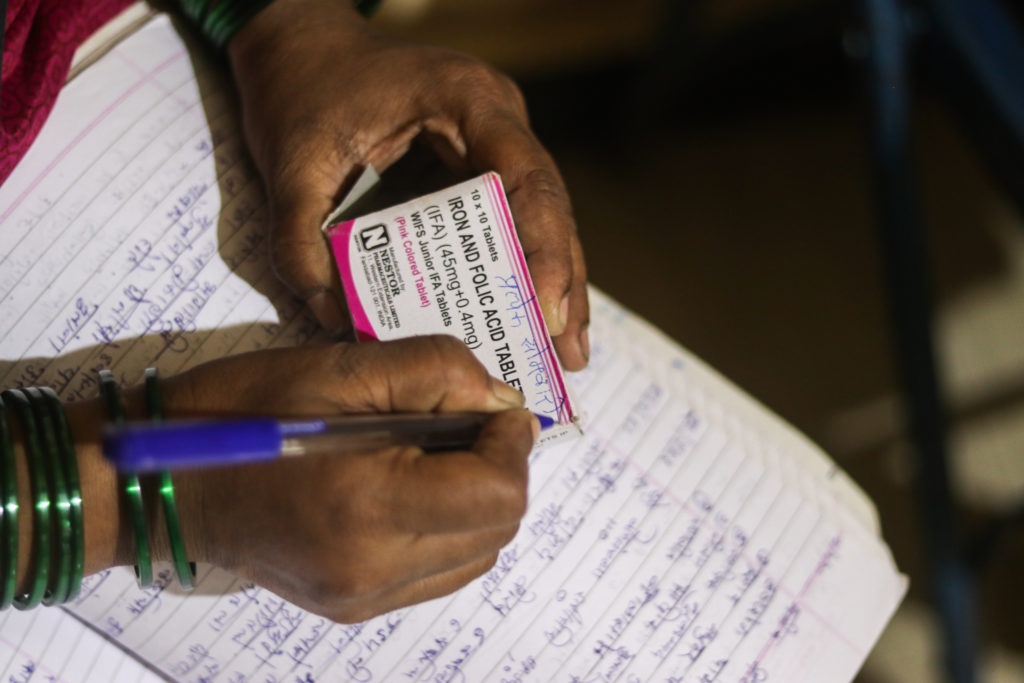

Prajakta Khade walked into a public health center daily for three months in early 2021, without ever receiving medical care. The healthcare worker’s 26 notebooks—containing more than 3,000 pages of community health records—point to why she couldn’t seek treatment for her ailments. She was simply too busy.

In March 2020, India’s health ministry tasked 1 million Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) like Khade with COVID-19 duty in rural areas. This, in a country where 65 percent of its 1.38 billion people live outside cities. Suddenly, ASHAs’ workload increased exponentially. Yet, they remain underpaid and now suffer stress-related chronic ailments.

“If a positive case was found in the area, we had to visit the patient, contact trace, arrange medical facilities, measure their oxygen and temperature levels daily, and ensure they complete quarantine,” Khade explained about the added duties to treat the infectious respiratory disease. But all Khade was given to do her job in the assigned area in India’s Maharashtra state was a single N95 mask and 200 milliliters of sanitizer.

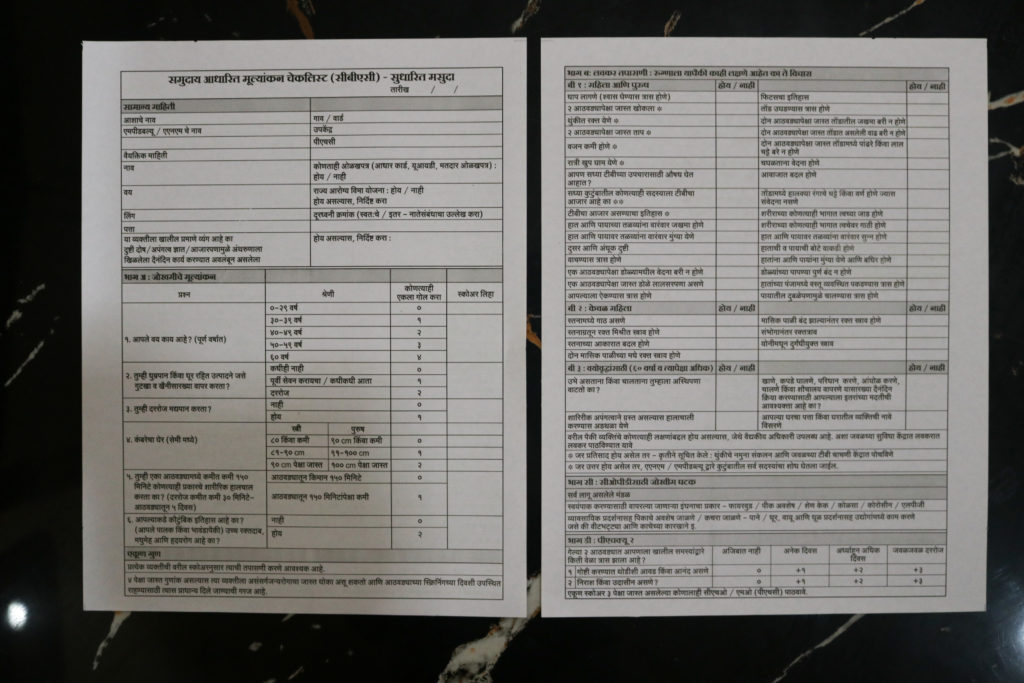

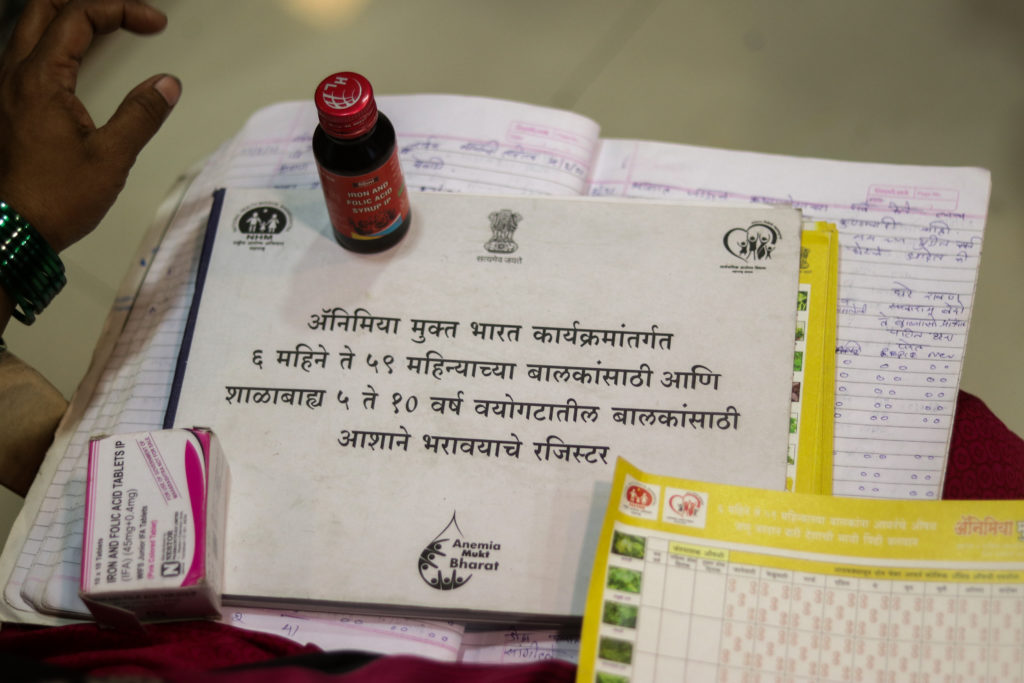

ASHAs, an all-women healthcare cadre, remain the foot soldiers of India’s rural healthcare. One worker is appointed for every 1,000 citizens under India’s 2005 National Rural Health Mission. ASHAs are responsible for more than 70 tasks, including providing first-contact healthcare, counsel regarding birth preparedness, and pre- and post-natal care. Plus, they help the population access public healthcare and ensure universal immunization, among other things.

The World Health Organization announced a pandemic in March 2020. But in many countries, lack of adequate healthcare and no social safety nets amid lockdowns wrecked the lives of ordinary people. In India, for example, an additional 150 million to 199 million people are expected to enter poverty in 2021 and 2022.

Chronic Illnesses Spike

One day about a year ago, while surveying people in her village of Vhannur in India’s Maharashtra state, 40-year-old Khade felt dizzy. But she couldn’t take a break. “At one point, my face was swollen, and I could barely see anything.” It turned out her blood pressure level had surged to 252/180 mmHg (millimeter of Mercury), much higher than the standard limit of 120/80. That is how she got diagnosed with hypertension.

However, a month’s worth of medications didn’t help because she continued to experience stress as her workload increased. Senior officials at the health center had early on issued an order to submit patient records daily by noon.

ASHAs, who aren’t considered full-time workers, receive performance-based incentives paid on the number of tasks completed. “For COVID duty, the government decided our worth as merely 33 Indian Rupees per day (43 U.S. cents),” she said. “We received this amount only for three months in the past two years.”

Moreover, during the peak of COVID-19 cases in 2021, salaries for Maharashtra’s ASHAs were delayed by five months, according to Khade. Netradipa Patil, an ASHA from Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district and leader of a union that represents more than 3,000 ASHAs, confirmed this.

One day last year, Khade’s supervisor asked for a list of hypertension and diabetes patients from her village of about 1,200 people—at 10 o’clock at night.

“How could I survey the entire community in the night?” she asked.

Often, such orders meant skipping lunch and staying hungry for 11 hours at a stretch. ASHAs worked four hours prior to the pandemic. Now, 12-hour days are normal.

When medications didn’t help, Khade consulted two private doctors. “After six months of hassle, the doctor doubled my dose to 50 milligrams.” Khade lost over 10 kilograms (22 pounds) of weight and was placed on medications to address anxiety. Even today, she suffers from fatigue.

“I was never this weak,” she asserted.

Chronic diseases among ASHAs are rising rapidly because of the workload, says Patil. “We protect the entire community, but there’s no one to look after our health.” ASHAs in Maharashtra, she says, average a monthly income of Rs 3,500 to 5,000 ($45 to $66 USD).

This reporter spoke to ASHAs’ senior officials from Maharashtra’s Kagal block. (In India, a cluster of villages form a block and several blocks form a district. Vhannur village is in the Kagal block of Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district.) Senior officials said they are not responsible for ASHAs’ deteriorating mental and physical health, and pointed to the Indian government’s order to submit data. The officials didn’t want to be named. Instead, they relayed that they also are overworked.

“ASHAs do the majority of the health department’s work, and they are massively underpaid for their duty,” said Dr. Jessica Andrews, a medical officer at Kolhapur’s Shiroli Primary Health Center. She has been handling mental health cases. “Without them, the health system will collapse.”

‘Not Treated As Humans’

Several ASHAs across India have worked for over a year without a break. One of them is Pushpavati Sutar, 46, diagnosed with hypotension (low blood pressure) and diabetes within seven months of COVID-19 duty in November 2020. Like Khade, she experienced constant spells of dizziness.

“Often, there was fake news of community COVID transmission in my area,” she said.

Every day, senior officials at the health center hounded her to find more details about such instances.

An ASHA for 13 years, she’s never made an error in her surveys and was sure of no community transmission. “After investigating, I found that the accused was COVID negative. Instead, two of his relatives were positive.”

She had to clear such misconceptions almost every day, answer senior officials’ questions, collect records and perform her regular duty. “For several days, I couldn’t sleep,” she remembered.

Further, fearing COVID-19 guidelines and quarantine rules, community members began demanding ASHAs hide COVID-19 cases. “People even accused us of spreading COVID as we would survey the entire village,” Sutar recounted. Moreover, she said senior officials asked ASHAs to visit the families of COVID-19 patients—instead of allowing data collection over the phone—putting them at risk of infection.

“At several places, there have been instances of community violence, where ASHAs were beaten up,” said Patil, who has filed legal complaints on behalf of the assaulted workers and is helping them mentally recover.

Kolhapur’s ASHA union has written to several government authorities, including Maharashtra’s chief minister and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, highlighting the mental toll of COVID-19 duty. Still, none of their letters have garnered a helpful response.

“Forget adequate pay,” said Khade, as she continued surveying, juggling between completing her task and trying to keep her mind at ease. “We are not even treated as humans.”

Sanket Jain is an independent journalist based in the Kolhapur district of the western Indian state of Maharashtra. He was a 2019 People’s Archive of Rural India fellow, for which he documented vanishing art forms in the Indian countryside. He has written for Baffler, Progressive Magazine, Counterpunch, Byline Times, The National, Popula, Media Co-op, Indian Express and several other publications.