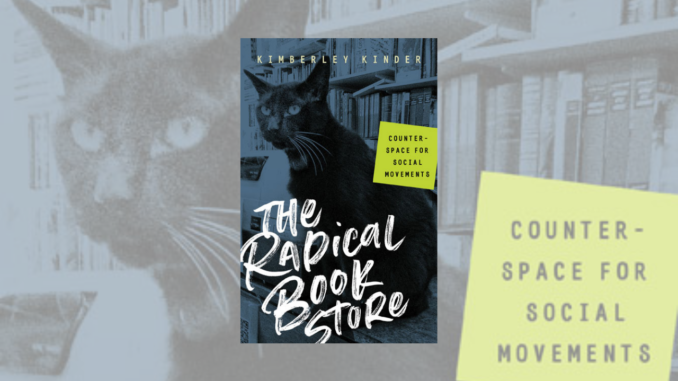

The Radical Bookstore: Counterspace for Social Movements by Kimberley Kinder. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2021.

In the final hours of 2008, I moved to Philadelphia. George W. Bush was still president, as Obama began assembling his team of neoliberal economic advisors to bail out the banks that had just crashed the economy. Before I was able to find a wage job during the height of the recession, I picked up a volunteer application at the local anarchist bookstore. By early 2009, I had finished my training shifts and was quickly given keys to the Wooden Shoe.

Founded in 1976, Wooden Shoe Books and Records is an all-volunteer collective where all decisions are made by consensus at monthly meetings open to all staffers. When I joined, the lease at its location on Fifth Street was about to expire, so I participated in the process of moving to its current location on South Street. It was an exciting time get involved and a perfect way to find instant community and camaraderie in a big city where I had never lived before. I stayed in Philly for over 12 years and was involved with the bookstore for most of that time; the only constant in my life there.

In her new book, The Radical Bookstore, University of Michigan professor Kimberley Kinder studies spaces like the Wooden Shoe and the role they continue to play in movements for social justice and transformation. She highlights the importance of brick-and-mortar “counterspaces” that help sustain organizing and movement building in between bursts of protest activity in the streets.

The criteria for the 77 bookstores, infoshops and community centers she researched was limited to “print-based movement spaces.” They are all public-facing physical venues that include a focus on print objects and their missions are oriented toward radical left activism. They all “approach their business primarily as social movement tools.” (Infoshops are autonomous, typically anarchist spaces. They tend to include do-it-yourself zines from the community and provide space for activist meetings and events. Some have less of a retail component, and might offer a free library and other mutual-aid services.) Kinder calls this “constructive activism,” a term she adapted from feminist geographers like Daphne Spain, which “highlights the material base of social organizing.” With a focus on mechanisms over particular issues, the book explores the crucial contributions of such durable spaces in the ongoing struggle for a better, more just world.

So, it made sense that Kinder reached out to the Wooden Shoe in April 2017. She had visited the store the previous summer and was interested in speaking with a member of the collective more in depth, so she could include us as a case study for the book. I volunteered and we spoke on the phone for about an hour about my experiences with the Wooden Shoe and to fill in some of the blanks beyond the information included on our website. We discussed some of the political goals of movement-oriented spaces and our aim, as anarchists, “to challenge structures of domination and oppression.” We also talked about how the Wooden Shoe is volunteer-run and how that has played a big role in sustaining the business for over 40 years. I explained, “If we were depending on paying ourselves, we probably would have [closed].” I also compared our success with other similar collectives that had recently gone out of business: “They had at least some members that were being paid and depending on that space for their livelihood.”

The two I had in mind were Food for Thought Books in Amherst, Massachusetts, which shut down in 2014, and Rainbow Bookstore Cooperative in Madison, Wisconsin, which managed to stay open only a couple years longer after a decade struggling to compete with corporate online behemoths like Amazon. I had the privilege of volunteering at Rainbow from 2004 to 2005 and, even back then, the staff collective was struggling to find creative ways to encourage students to buy textbooks from their local cooperatively managed, worker-owned shop, instead of ordering them online from a chain store. “You have nothing to lose but your chains!” exclaimed Rainbow’s posters across the University of Wisconsin campus. But by 2016, Rainbow could no longer afford to compete.

In The Radical Bookstore, Kinder briefly traces this history of “activist-entrepreneurs,” favoring the independent bookstore model in the 1960s and 1970s. This was an effective strategy not only for disseminating radical ideas, but for creating alternative spaces for movements to build and grow by tapping into the consumerist impulse permeating across the United States. The financial effectiveness of this model began to dwindle in the 1990s when two-thirds of all indie bookstores went out of business as a result of economic restructuring policies. Despite more recent examples, like Food for Thought and Rainbow, Kinder cites a slight resurgence of independent shops since the year I began staffing at the Wooden Shoe, 12 years ago. She argues this is a result of some “reformatting as events-oriented, nonprofit hybrids” and also because of “trends like ethical consumerism” that involve supporting local businesses.

Despite the grim reality of increased corporate consolidation, gentrification, and the ubiquity of digital media dismantling so much of this thriving network of radical bookstores and other “print-based movement spaces,” Kinder argues that analyzing the “constructive dynamics provides an important antidote to the usual narratives of decline.” Even though it is more difficult now to replicate the business models of the past, she explains, “Focusing only on the postmortem of victims misses an equally important opportunity to study why some places survive and thrive.” Adding that, “By looking at stories of resilience and innovation, scholars and activists can potentially find the nuggets of a blueprint for emerging business models that make independent spaces viable, even in a corporate, digital age.” (page 79)

Nearly 45 years after it was founded, the Wooden Shoe is just one of many counterspaces that have managed to survive and thrive. This has particularly been the case in recent years as increasing numbers of people have become radicalized through the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements, in addition to the election of Trump and the subsequent rise of the fascistic “alt-right.” During this period, I helped organize and host dozens of in-store events that brought all kinds of people into the space, from author talks and panel discussions to film screenings and potlucks. And more recently, the COVID pandemic has reminded us how important autonomous, physical space for organizing truly is, as we collectively struggle with the isolation and alienation of the past 16 months.

This past April, I left Philly and moved to Boston. My new apartment is walking distance from an even older anarchist bookstore: The Lucy Parsons Center. Like the customers Kimberley Kinder met there during her research, I often visit the infoshop, founded in 1969, “to find a sense of camaraderie.” And now that I no longer host events through Zoom for the Wooden Shoe, perhaps, one day, I’ll start volunteering there, too.

Matt Dineen is a writer and activist based in Boston. He has written for Toward Freedom since 2005.

The Water Defenders: How Ordinary People Saved a Country from Corporate Greed by Robin Broad and John Cavanagh. Boston: Beacon Press; 2nd edition. March 23, 2021.

The Water Defenders: How Ordinary People Saved a Country from Corporate Greed by Robin Broad and John Cavanagh. Boston: Beacon Press; 2nd edition. March 23, 2021.