Cancel This Book: The Progressive Case Against Cancel Culture, by Dan Kovalik (Hot Books: New York, 2021)

Academic and activist Dan Kovalik’s new book, Cancel This Book: The Progressive Case Against Cancel Culture, was written on the frontlines of the twin struggles of our time, the class struggle and the fight for Black liberation. Reading it brought me back to so many magical and contradictory movement moments that I could not resist writing a review.

‘White People Go to the Back of the March’

On the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Day in 2017, thousands of protesters took to Fifth Avenue and the frigid streets of New York City to demand criminal charges against the police who murdered Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge; Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota; and hundreds of other unarmed Black and brown men. Some Black Lives Matter march marshals had determined that Black and brown families and activists—presented as the only real victims and fighters—would march in the front. White people—presented as all equal benefactors of white supremacy and white privilege—were assigned to march in the back, separated from the youthful, militant front. It was a strange scene. Forty-nine years after the U.S. state assassinated Dr. King for risking his life to organize a multiracial movement against white supremacy—and in his final months, a Poor People’s Campaign against the capitalist system—surely he would find it curious we no longer needed outright white supremacists like Bull Connor or George Wallace; we were now capable of segregating our own marches.

So many questions leapt into my mind as my eyes traced the 10-block-long protest. Where did poor whites belong? Veterans? Whites who had been through the prison system? How about Black students who had both parents in a position to pay their tuition out of pocket at NYU or Columbia? They had all earned the front? Then there was my Ernesto Rafael, my son, half Dominican, half poor-white, harassed by the police too many times in the Bronx. Where did he “belong,” according to the marshals?

This was but one example of the new racial dynamics on display across the country in the BLM movement from Oakland to Boston, and everywhere in between. For class conscious revolutionaries throwing down in the heart of this mass movement, it represented a series of fresh, unique challenges.

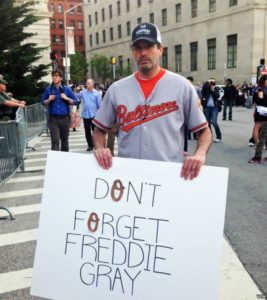

When I picked up Kovalik’s new book, I was intrigued by his biting class analysis of the similar experiences he had. In chapter 2, “Cancellation of a Peace Activist,” he writes directly about being a participant on the frontlines of the BLM movement in Pennsylvania, ducking and dodging police batons as organizers collectively figured out their next strategic moves. Kovalik, a union and human rights lawyer and professor, based out of Pittsburgh, dives deep into the contradictions he and so many others experienced. Kovalik slams both the arrogance of isolated white anarchists whose faux militancy puts all protesters at risk, as well as the bullying tactics and racial reductionism of some radical liberals. This took me back to the explosion of protests following the police murders of Eric Garner and Michael Brown in 2014, which brought millions of people into the streets to denounce the epidemic of police terror in Black and brown communities. Millions were in motion and different political tendencies vied for leadership. Kovalik examines key lessons to be drawn from the almost decade of collective experience we have as a movement in what came to be known as “Black Lives Matter.” This is but one must-read chapter in Kovalik’s exciting new book.

Woke Capitalism

Kovalik’s book is an expose of Woke Capitalism and the cancer of cancel culture.

While millions took to the streets to stop President George W. Bush from invading Iraq, the peace movement was eerily silent when Barack Obama, the country’s first Black president, became “the drone-warrior-in-chief, dropping at least 26,171 bombs in 2016 alone.” (pg. 109) He critiques the peace movement for going quiet every time a Democrat is (s)elected to the oval office.

This page-turner exposes today’s liberal establishment, which touts “racial equity” without ever questioning the underlying structure that intensifies white supremacist control of society’s institutions. David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, is but one example of a liberal who bloviates over the U.S. Capitol rioters and their violent methods. Yet, he advocated for the bombing, sacking and recolonization of Iraq. (pg. VIII) The book exposes corporate and campus departments that pay hefty salaries to “experts” to lecture on “racial justice” without ever touching the structures that buttress white supremacy and racial and class segregation. These defenders of racial capitalism—from the academy to the pressroom—give political cover to hucksters, who make a killing by bullying white liberals into forking over money, lest they be labeled racist. As one class-conscious scholar sarcastically asks in Black Agenda Report: Do we really “wonder why these rural voters didn’t just go to their local Barnes and Noble to purchase a copy of How to Be an Anti-racist before the election?” Are all of the books that have emerged from the White Privilege Industrial Complex reaching that mass of “deplorables,” whom Arlie Hochchild refers to in her monumental sociological exposé as “strangers in their own land”? (“Own land” as in stolen Indigenous land).

Kovalik takes on the Frankenstein-esque outgrowth of cancellations in academic institutions and beyond, asking what are the political forces behind them? He offers the real-life example of the canceling of Molly Rush, an octogenarian peace activist who reposted a quote that took on a life of its own. Instead of speaking with her face to face to clear the air, internet activists dragged her down and expelled her from the movement, like a group of pre-teens playing a game of Telephone. (pg. 13) Kovalik surmises that many keyboard warriors who have never stared down police lines or even handed out a flyer don’t want dialogue and growth. They want to score woke points and “likes” to the detriment of other comrades.

Liberal bully politics short-changes us all. Kovalik takes a big leap to the international realm to examine the West’s arrogant dismissal of Cuban medical internationalism, the Russian Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine and China’s success controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. China had two deaths in 2021. Kovalik concludes:

“It simply boggles the mind how the mainstream media and the Democratic Party elite are willing to compromise world peace and public health all in the interest of political gain. In so doing, they have taken ‘cancel culture’ to the very extreme, and they may get us all canceled, permanently, in the process…” (pg. 139)

We Never Give Up on Our People

It’s a new era. One tweet-turned-Twitter-game-of-telephone can ruin a comrade’s life.

How does the state operate online? How do anarchists operate online? When do they intermingle? Any anonymous account can start a smear campaign against any public figure.

This book invites us to ask: If we cancel every last screw-up, addict and lumpenized scroundrel, who will absorb the body blows needed to bob and weave forward in the class struggle?

When in history has another social class organized, led and defended a revolution? The petite-bourgeoisie blows with the wind. Who will be left? Who is willing to put in that work? Who knows hell well enough not to fear it? Nicaraguan national hero Augusto Sandino said, “Only the workers and peasants will make it all the way.” Kovalik is not turning his back and giving up on the potential cadre of the future. Will you?

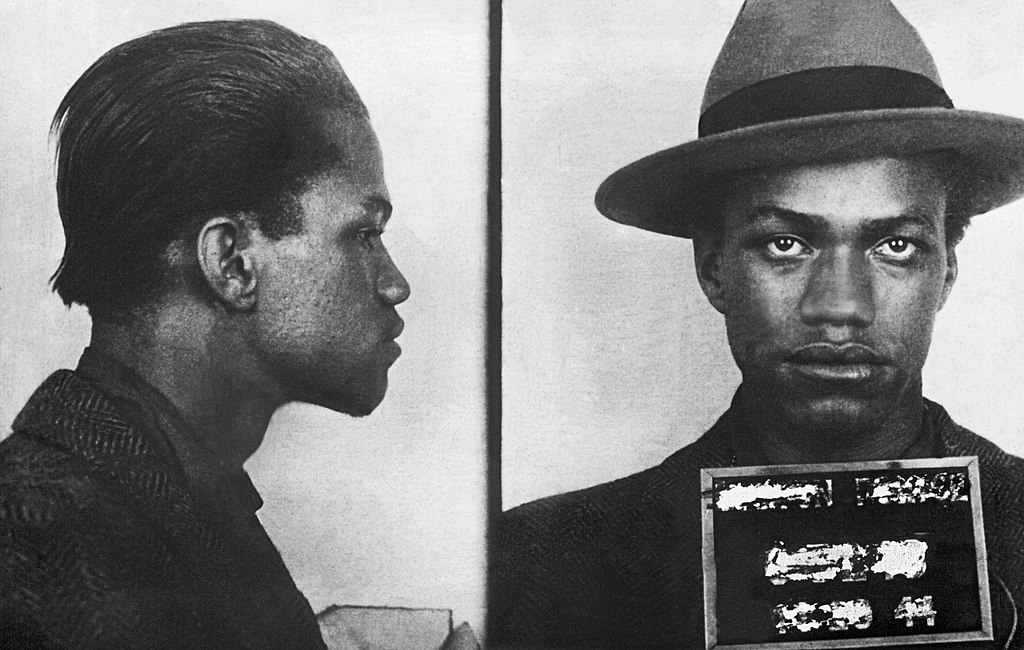

As Marxists, revolutionaries and anti-imperialists, we believe nothing is permanent; everything is in a state of flux. The watchwords are growing through contradictions among the people, healing and restorative justice. We don’t have the luxury of discarding comrades. There has to be a path back or we risk cannibalizing and condemning our own ranks. Who would Malcolm X have been if everyone had given up on him in his 20s, when he was imprisoned? How many young Bobbies, Hueys and Assatas are sidelined right now? How can we be less judgemental and give people opportunities to learn from their mistakes?

The Other White America

Black and Brown people in the United States, and those in solidarity with the Black Liberation Movement, have every right to be angry. But angry at whom?

Most white people are not CEOs or members of the ruling class; many more are National Guard soldiers, correction officers and other reactionary rent-a-cops, the overseers of a society divided between the haves and the have-nots. But the racial portrait of state repression is more complicated. Fifty-eight percent of the Atlanta police force is Black. Over half of Washington, D.C.’s police force is Black.

A liberal portrait of white privilege fails to tell the full class story in the United States. Seventy million people received Medicaid in 2016—43 percent were white. Of 43 million food stamp recipients that year, 36.2 percent were white. Over 100,000 overdoses took place in the past year. The overwhelming majority of opioid overdoses occur among poor whites, roughly 72 percent. Are these cast-off layers of our class our enemies?

Kovalik points out that similar to white people, “the top 10 percent of Black households hold 75 percent of Black wealth.” (pg. 96) Is every brother your brother?

Given the complex class and racial terrain, do we cast poor and working-class whites away as “a basket of deplorables” or do win them over to defend their class interests? Wouldn’t sticking all white protesters in the back of marches with more yuppified layers only alienate them more? Is the movement a “safe space” for them, or more importantly a revolutionizing space?

Cancel This Book refuses to give up on the other white America—the poor, forgotten and de-industrialized “oxy-electorate” (writer Kathleen Frydl’s term for white people who live in the U.S. Rust Belt, where OxyContin addictions are on the rise). Those white people are full of disappointment and hatred for this system—between the tens of millions who refused to vote for another neoliberal Dixiecrat like Hillary Clinton, and the tens of millions of others who were duped into believing a spoiled, trash-talking, billionaire, real-estate mogul hoax and punk with infinite air time was their white knight.

As Malcolm X taught: “The truth is on the side of the oppressed today, it is against the oppressor.” We can win over workers who have only ever known the american-dreaming chauvinism they have been fed. Bursting with ideological perspicacity and revolutionary hope, this book pushes us not to get caught up in the liberal webs of identity politics and call-out culture.

Kovalik also challenges the white liberals who unknowingly acted as “masochists at the protests.” This constructive critique is not meant to take away from anyone’s hard work and real contributions. Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ) was one outgrowth of these liberal politics, which relegated many well-intentioned, liberal, student and petite-bourgeoisie (“middle-class”) whites to cheerleader positions. Is this the militant mass-movement that is going to stand up to the State Department, the Pentagon, the police and the intelligence agencies? When Malcolm held up white abolitionist John Brown’s life as an example of real struggle to follow, he was challenging these liberal politics.

Amidst the ever-evolving dialectics of our movement, Kovalik’s book comes as a breath of fresh air. It is a clarion call about the damage we are collectively doing to our movement if we do not center class politics next to the need for Black liberation and the liberation of all oppressed people.

Danny Shaw is a professor of Caribbean and Latin American Studies at the City University of New York. He frequently travels within the Americas region. A Senior Research Fellow at the Center on Hemispheric Affairs, Danny is fluent in Haitian Kreyol, Spanish, Portuguese and Cape Verdean Kriolu.