Traditional mortuary rites are no longer enough in Mexico, where a new trade has come to exist over the past few years: that of the bone searchers. In Veracruz, one of the deadliest states in Mexico, six men have the job of digging through clandestine graves for the human remains hidden there. For the most part, they are not parents on the trail of their disappeared children, nor are they volunteers. They are day laborers, who dig the land in exchange for a salary paid by relatives of the disappeared, in a country with more than 40,000 disappeared and more than 240,000 murders over the last 12 years.

He speaks to the dead even if he’s never met them.

“My friend, if you are there, give me a sign.”

Whatever’s left of a person is stuffed into a garbage bag, buried under the ground.

“My friend, if you are there, give me a sign. Or when I go to bed, let me know in a dream where I have to look for you tomorrow. Talk to me.”

He names them with kindness as he walks over layers of sand blown in by the wind. He stares at plants and weeds. He tries to find a discrepancy on the surface of the land, a tree that might have been useful as shelter. Where many can only see green or brown, he reads stories.

“I’ve known the fields and the fields tell me many things,” he says.

Gonzalo Gómez García is a man of stern gestures, bushy eyelashes and thick eyebrows. He is 37, but looks like he is in his late forties. It could be his sun-leathered skin: he has worked in the fields since he was eight.

“My childhood was very bitter. I didn’t go to school, I’ve never learned to read. I also took drop-in classes but I couldn’t read. I go, I learn and, at night, I forget it all,” says Gómez García, his mouth turning up into a smile, his sadness forgotten like a piece of paper thrown into the trash.

In Colinas de Santa Fe, on the outskirts of the city of Veracruz, this good-natured, strong armed man began again to listen carefully to the field before him. He identified a tree, detected that the natural harmony of the surface of the land had been interrupted, and pointed at a place to dig. There, many of the largest graves were found. There were 155 graves, to be exact, from which 302 bodies and almost 70,000 bones and bone fragments were recovered.

Gómez García, a farmer who does not read or write, has become part anthropologist, part forensic expert; part archeologist, and part laborer. He became a bone searcher, a new trade that shows the cracks in a country with more than 40,000 disappeared people and over 240,000 murders over the last 12 years.

The first time he found a body, Gómez García felt a chill.

“My friend,” he said to the bones, “I am not here to harm you. Forgive me if I hurt you, I have to dig because I have to find you.”

Almost three years after that first find, his workday is finished. He sits on a plastic chair underneath the shadow of a mango tree. Fresh air blows, birds chirp, at the back of his yard his youngest child splashes in an inflatable pool.

Gómez García and his family live at the end of a dirt road in a town of less than 250 inhabitants, in the municipality of Medellín. Nearby, the grey blocks of unfinished houses lay bare, with palm trees and trees pushing through their courtyards. Every day when he comes back from work, Gómez García has an afternoon snack with his teenage daughters, plays for a while with his seven-year-old son, and talks to his wife Rosalba by the kitchen stove.

His dog Osa follows him wherever he goes, her tail wagging. His hens immediately surround him when he calls. The owner of the land allows Gonzalo’s family to live there, in exchange for looking after the property.

“When I found the first person I was so happy, happy in a good way,” Gómez García explains in a charismatic coastal accent. He is visibly touched by the memory. “Happy because it would give peace to a mother, a sister, a wife.”

His most recent finding was on December 12, 2018 at 11:30 in the morning. He found a femur —the longest bone in the human body— as well as a fibula and part of a person’s foot. From the first to the last, Gómez García spoke to them all.

México’s insides are filled with bodies. Some belong to the thousands who have been murdered and disappeared over the last 12 years. Others belong to the slaughtered and disappeared during repression in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

“We walk on a carpet of old and new bones,” writer Elena Poniatowska has said. Far from ending criminality, mass violence increased with the so-called war on drugs, the security strategy that started with President Felipe Calderón in December of 2006, and continued until the end of 2018 with Enrique Peña Nieto. The new administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) has shown few signs of wanting to reduce militarization.

There is a connection between the past and the present. Anthropologist Alejandro Vélez Salas talks about how a “pedagogy of terror” has been installed in Mexico, as different types of violence have been passed along and spread around.

“Mexico is a huge grave,” said Alejandro Encinas, who is AMLO’s new undersecretary of Human Rights. And though a new law forces the government to keep a National Registry of Clandestine Graves and Common Graves, there is still no official database. The information is scattered across the regional offices of prosecutors in 32 states, the office of the Attorney General, the Navy, the Army and the Federal Police.

It is perhaps no surprise that the government appears to be under recording mass graves: Encinas mentioned 1,100 clandestine burials. But according to the information we received through access to information requests, newspaper counts and lists created by family groups of the disappeared, between 2000 and 2017, more than 2,700 such graves were found in Mexico. If we add those found in 2018, the number of graves would rise to over 3,000.

Veracruz is the state with the most clandestine graves in Mexico: as of December 2018, there were 505. And Colinas de Santa Fe area is the place where the most bodies have been found. In the parched ejido (communally owned land) of Patrocinio, in the northern state of Coahuila, families of the disappeared sift through the desert to recover tiny bones. There, the largest fragment could measure three centimetres across, so they move the human remains in buckets and count them by weight. In Tijuana, families seek to recover litres of organic matter after a man named Santiago Meza confessed to dissolving 300 people in caustic acid.

This Mexico shakes and silences even the most hardened of experts, like the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (the EAAF, by its Spanish acronym). The EAAF has more than 30 years of experience recovering bodies, they have dug in more than 50 countries and are considered a global authority on exhuming clandestine graves.

But they have never before seen a reality like this.

Their work traditionally takes place following a war, a dictatorship, or an internal conflict. “What’s happening here is that the problem continues,” said Mercedes Doretti, the EAAF director for Central and North America. She always looks serious, like she’s measuring her words. “I don’t like to say that one case is worse than another because all the cases are very serious, massive,” said Doretti, going a little silent, and before her words rumble louder. “But one of the characteristics in Mexico, which makes it different from other places where we have worked, is that the problem continues. It continues and exists under a democracy.”

“Is the real dimension of the situation known?” we ask. “No,” she says. “But its large volume, severity and complexity is.”

There isn’t an official national registry of how many human remains have been recovered in México. As of December 2017, according to information acquired through access to information requests, at least 6,400 bodies and 183,000 long and short bones, fragments, and bits of teeth have been recovered.

Identifying these bones is a difficult task for forensic science. Government institutions confirm that as of December 2017, they had identified the bodies of 2,000 people, but only 800 of them, or what was left of them, were returned to their families. There’s no certainty about the fate of human remains in the custody of the Mexican government. Many families have refused to accept bone fragments, as they do not trust the government’s identification.

Following the trail those who are identified is like trying to put together an impossible puzzle, a puzzle that also has pieces missing.

About fifty groups organize search brigades from the north to the south of Mexico. Most of them are relatives, friends, and volunteers, but in Veracruz, Colectivo Solecito (Little Sun Collective) decided to go one step further: they began hiring day laborers as exhumers, as bone searchers.

A group of six men, including Gómez García, works Monday through Friday searching for bones in Colinas de Santa Fe, the largest clandestine mass grave in contemporary Mexican history. Only one of the men has a missing relative. All of them search for bones in exchange for a paycheque.

“They are workers,” says the director of Solecito, Lucia de los Ángeles Díaz Genao. “We are generating employment.”

Díaz is an elegant woman who can usually be found in earrings and sunglasses. She has a sharp face, short hair and glossed lips. Díaz is a linguist whose son was disappeared on June 28, 2013. His name is Luis Guillermo Lagunes. Armed men took him from his home.

Díaz and other members of Solecito, who are mostly women, decided to hire men to help dig when they realized that the graves were two meters deep.

“We saw that it was very deep and we couldn’t do it because some of us have high blood pressure, others are diabetic, and as soon as we get to the grave site it causes such an intense feeling that some of us get sick,” explained Rosalía Castro Toss. Castro Toss is the second in command at Solecito, and mother of Roberto Carlos Casso Castro, who disappeared on December 24, 2011.

Now, they have a list of workers, and manage contracts and payrolls with differentiated salaries. The anthropologist earns about 10,000 Mexican pesos per month, (around $506). The rest are paid far less, some half as much.

The group’s costs run about $500 dollars per week, an impossible sum for families that live on the edge of poverty. A national institution, the Executive Commission of Attention to Victims (CEAV, by its Spanish acronym), provides the families with some resources and lends them a van for travel, but it is far from enough.

And so, the mothers of the disappeared raise money in every way they can think of: they receive cash donations and used clothing, which they then sell in bazaars, they organize bingos and raffles. A pair of shoes were sold at eight times their original value in an auction on a social network. Peso by peso, they have financed almost three years of work in the graves at Colinas de Santa Fe. To date, it has cost them $1,300,000 Mexican pesos: almost 70,000 dollars.

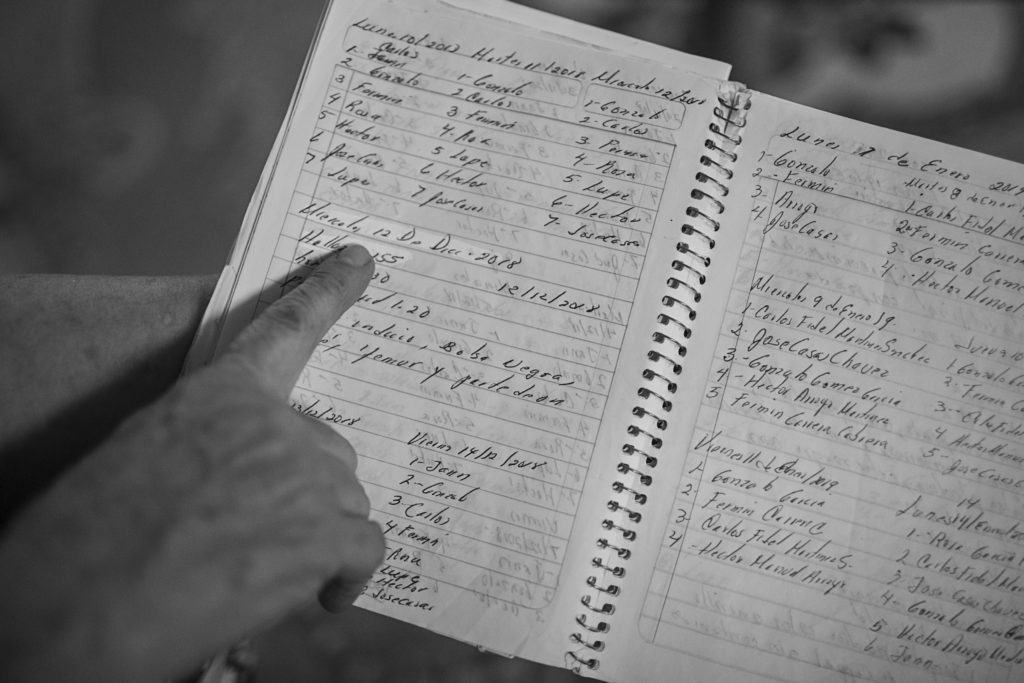

Shovels, hammers, rods and machetes are the tools of the trade, as are notebooks, pencils and cell phones to take pictures. The searchers mark the land they have already worked on with a code written on paper that they put inside a plastic bottle. There are few resources and a lot of risks: a possum once entered a grave, chewed the bottle and took the paper with him.

We met at the entrance of a Walmart in the port city of Veracruz. Fermín Cabrera called us to the parking lot, which was empty. All white, all grey, a blue logo. Cars pass by, using the parking lot as a shortcut to get around a busy avenue. Cabrera doesn’t want to take a seat outside or inside the car. He stands, focused, looking around. He doesn’t want us to visit him at his house or take pictures of his neighbourhood. He doesn’t want to tell anyone because he feels he is at risk. He tries not to say where he’s working or what he’s looking for.

“Someone can immediately point me out: he is the seeker of the dead.”

A comadre asked him to join the brigade to find his son, a boy named Pablo Darío Miguel. Cabrera accepted. Since then he always goes to the graves with the same clothes, it’s like his uniform. He speaks of adrenaline, of a sense of achievement, of finding bones and feeling that his efforts under the heavy sun were not fruitless.

He is sullen but he likes talking, watching the news on television and practicing boxing. He learned to box at school to defend himself because he was a slight boy. “Everyone wanted to hit the dwarf,” he said.

“The dwarf,” he repeats to himself. He repeats the word with an echo of resentment, but then he smiles again, kindly. He explains that he also works in a factory and that he is a physician, trained at the University of Veracruz. He says that he participates and works easily, that he has learned a lot.

Carlos Fidel Martínez was a boy who played with dinosaurs. In his teens he was passionate about World War II, its crimes and its graves. He studied archeology, but in recent years he began to understand that his profession is not a glamourous one. Archaeologists in Veracruz have a less exciting life than people may imagine: they supervise pipelines of belonging to Pemex, México’s state-owned oil company, and do studies for private companies, such as the reports a supermarket chain would require before building a new franchise.

Martínez met Lucy Díaz during a course on forensic science held by the state university. Initially, the relatives wanted to use machinery to dig up Colinas de Santa Fe, authorities demanded the presence of an archaeologist. When they invited him, Carlos accepted without hesitation. He quit his previous job, even though he was earning double.

“I do this because I like it a lot. I always take jobs that I like, I never ask about the payment,” he said. “I want to live the experience.”

Martínez is tall and young and looks like a big boy. He’s the expert, but he doesn’t act any differently from those around him, who he respects and values. He is dark-skinned, wears glasses and ties his curly hair in a ponytail. His father is a retired public employee, his mother, a massage therapist.

“A bone is a bone. Inside the grave I work on autopilot, I put on my archeologist suit,” said Martínez. “But once outside, I think about the people buried there. I think about it a lot.

Martínez enjoys Discovery Channel documentaries, listening to music and spending hours in front of his Nintendo. His favorite game is The Legend of Zelda, a video game from the 1980s that’s all about rescuing a princess.

Guadalupe Contreras is the only one of the six bone searchers with a missing relative: his son Iván Contreras. Iván was disappeared on October 13, 2012, when he was 38 years old. He is the father of three children, who now are 13, 10, and eight years old.

Don Lupe, as he’s known, was born in the state of Guerrero. He is slight, with sun-tanned skin. He left his village due to a drought that put his farmer father and family of nine children in trouble. Don Lupe’s mother worked washing other people’s dishes, he began working at the age of nine in the fields, planting corn, bean and sesame.

“When I turned 13 I went north, between Houston and Dallas. I knew that my grandmother had money saved and I took it from her,” he said, laughing openly, showing his missing teeth. “But later I returned it. I crossed the border with a friend, there was no surveillance. We worked on a ranch, feeding a crappy herd of buffalo. I came back because I wanted to see my brothers, my mother. In three years I had never sent a letter to them, they thought I was dead.”

He never went back to the United States.

Don Lupe has been a farmer, a migrant worker, a soldier, a bricklayer, a mason, and now he’s a bone searcher.

“I’ve been many things. My boss used to say that ‘boredom is the mother of science.’ But if someone had told me ten years ago ‘you’re going to be a searcher,’ I would have told them to fuck off,” he said.

When Don Lupe realized the unwillingness of authorities to search for the disappeared, he decided to go out on his own to look for his son in the hills of Iguala, the same city where the 43 students of Ayotzinapa were disappeared. He was one of the first searchers, and later became a member of the search group Los Otros Desaparecidos (The Other Disappeared) in Iguala. The mothers who are part of Solecito learned of Don Lupe went to look for him and offered him a job, which would also become like an education. Don Lupe is strong, charismatic, and easy-going.

“When a body is decomposing, the grass doesn’t grow, it turns yellowish because it emits gases. When the body has already decomposed, it serves as fertilizer and the grass turns green,” said Don Lupe, sharing one of his lessons. “At the beginning, when you spotted a bone you wanted to cry because you didn’t know if it was your relative. But finding so many corpses makes you stronger.”

Don Lupe smokes one cigarette after the other. He thought he would stay three months in Colinas de Santa Fe, it’s been almost three years. He has the most experience with exhumations in the group, and has shared what he has learned with groups from Sonora and Sinaloa. He keeps in touch with many family members on a daily basis via chat.

The boardwalk in the Port of Veracruz is perfect. There are small stone benches with curved and avant-garde designs, still wrapped in plastic, waiting to be used. There are new sculptures, minimalist gardens and concrete squares, kind of like postcard frames to take pictures or to see the sea as if though a large peephole.

The sun is rising. Boys and girls run in matching steps, coordinated, chanting snappy slogans of success, effort, and strength. They pass by in several groups. They all wear the same uniform: polyester sports pants and a white t-shirt with the word “Navy” on the back. They are the future marines who will later join the most powerful branch of Mexico’s armed forces.

A mother prepares her daughter’s costume for the carnival. Everyday life is like a bright street, the rough figures are kept in the shadows. A new grave was found in Sayula de Alemán, closer to the sea, and five new graves in Río Blanco, up into the mountains. But nobody talks about that.

The marines cruise, patrol, move through the city. They are everywhere, except in the poorest and most violent neighbourhoods. There is not one of them where the six bone searchers are looking for human remains.

Colinas de Santa Fe is like a hole in the middle of a large green carpet. It is 12 kilometres from the hustle and bustle of Veracruz, the most important port in the country. It is an island of sand that can barely be seen from the air in a strip between the Gulf of Mexico and Highway 180, a fearsome road that leads to several more clandestine graves (Rancho Renacimiento San Julián, Arbolillo, and La Gallera).

Colinas de Santa Fe is a clearing that looks like emptied, like nothing at all.

The road to the graves is private property. It starts in a small, working class neighbourhood built up with Mexico’s version of cookie cutter public housing. The area is rife with abandoned houses, there’s a 24-hour shop near the entrance from where clerks could easily have been witnesses to traffic passing on the way to bury people. The shop has been robbed many times. We are told the last time was just this morning.

At the start of the road into Colinas de Santa Fe, a rusty, beat up van is always parked in the same place. The faded “Ministerial Police” sticker on the vehicle is barely readable. Under the only tree that gives shade, there is a white car without official identification. A big man wearing tight pants and a cowboy belt sits in the car, he’s the police officer in charge of overseeing us today. A sleepy policeman, sent to protect lands studded with human bones, a scene that is repeated in other killing fields, such as Patrocinio in Coahuila.

There is no public access to the grave site, the authorities have it blocked off. They don’t allow access to media, or to people invited by the family members who belong to the Solecito collective. Veracruz’s state prosecutor, Jorge Winckler, seems determined to hide the place. We requested an interview with him for this story, he never replied.

The sand is hardened into a crust, but it crumbles when pierced with a metal rod. Carlos compares the work in the heat and humidity to being inside a boiling pot of tamales. Sweat runs down his face.

The brigade members pose for a group portrait: Gómez García, Don Lupe and Cabrera; Carlos and another archaeologist, José Casas Chávez. There are also two women who accompany the brigade on behalf of Solecito, bringing the workers payment: Rosa García Ramón, mother Óscar Omar Gómez García, and Jannette Helen O’ Relling Carranza, who is looking for her brother Rommel and five other relatives. The team is also includes a former local prosecutor, a man who flees from the photos, doesn’t want to be interviewed, and asks us not to mention his name.

Over the past few years, it has been practically the same group of people. Only one of the laborers left the group, his name was Daniel, a 30-year-old who was friends with Beto, Rosalía Castro Toss’ missing son. He didn’t know whether to continue to help or change jobs because his salary of $50 a week was not enough.

“It’s not enough. I play basketball and I can’t afford a pair of sneakers. The ones I’m wearing were a gift from the team leader and it’s been years since someone gave me a pair of sneakers,” said Daniel, who preferred not to give his last name for safety reasons. “I can’t even afford my boxers”

The risks are high: the bone searchers are not exempt from violence, and there are many poisonous snakes around. So far, they have found 11 vipers, they pack around a snake bite antidote with their tools.

Nightmares are also frequent.

“Being here is not healthy for anyone. You see the magnitude of the evil that this entails,” said Daniel. “What impacts you the most is finding skulls. Once I found a skull gagged with duct tape, kidnapper tape, as we call it.”

Gómez García remembers finding a light-skinned woman inside a sleeping bag. He remembers mutilated bodies, their arms cut to pieces, some partially burnt. When he started as a searcher, he would bathe before arriving at his house. He couldn’t sleep with his family and he would wash his clothes separately.

“Cloudy days are a relief,” Lupe smiles. We relax in order not to feel the time passing by, not to feel the pressure. We try not to get infected by what we’re seeing.

The searchers have a speaker and listen to music while they dig. The music gets the men arguing: some want to listen to a corrido, others prefer salsa and rock; the official bids for rap. His teammates clearly annoy him.

“At the beginning, I was surprised that they would listen to music,” says Martínez, the archaeologist. Narcocorridos make me feel a little uncomfortable but if they like it, it’s fine. I understand music now, it is a way of generating normalcy.

Not only does it happen here, most search groups listen to music while they walk and dig.

- Rea brand tank top/

- A pair of black Settia shoes, size 9.

- A pair of gray socks. Remains of garbage and towel and bandages. Toilet paper.

- A black size 6 Ferrys Active brand boxer.

- Optima size 40 tank top.

- Pressed black pants, size 40 or 44.

- Four skulls.

- 22 short bones.

- Black bag with fabric.

- Short bones.

- Short bones removed manually.

These are the findings from the grave on October 31, 2016. The details are written in a faded notebooks, with yellowed edges from constant handling. These notebooks contain the details of who attended the exhumation, if they found signs of a grave, if they removed bones or any objects, what the experts took, and anything else that might have happened.

This is data that authorities ignore and which could be crucial for a family member: the clothes a loved one wore at the time of their death, their belt, their favourite shirt.

Rosalía Castro Toss has written every word in the log. She is a woman with pale skin and gray hair with carefully dyed blonde highlights. She wears gold earrings, a smart watch and matching clothes. She has the soft and languid arms of an elder, the attentive gaze of one who listens with attention, and a strong, relentless character. Everyone calls her doctor because she is a well known odontologist in Huatusco, a small town with its park, colorful church and old ladies selling avocados and potatoes on the sidewalks. The moist lands, blue sky and fresh air among the coffee plantations feels endless.

The notebooks have some blank sheets.

“Because there was a time, two months, that I got sick of reading all this,” said Castro Toss. “I realized that it was killing me. Then I said to myself, ‘if I don’t do this, who will?’”

Castro Toss manages the logbook, and controls the brigade, she’s also in charge of one of Solecito’s three thrift shops. Hers is a small rectangular shop with a door and a window on the main street of Huatusco. There are two makeshift tables with easels, and the wooden remains of what was once a bed frame. There are also hooks hanging from the walls.

It mostly smells like soap and freshly ironed clothes, but the smell of mothballs also wafts in. Blouses and shirts cost ten Mexican pesos (50 cents), bags cost 30 pesos ($1.50) and party dresses cost 50 pesos ($2.50).

“Tomorrow I’ll come to get this shirt and this princess costume,” says an old lady from the sidewalk who walks slowly with the help of a walker.

The thrift shop is set up in what used to be the waiting room of Castro Toss’s odontology practice. She has weeks during which sales are good, when she sells over $250 worth of clothes, and others where she sells just $25. She is there not only to raise money: part of the purpose is to inform her neighbours about the work of Solecito. Castro Toss has been threatened several times. She has confronted prosecutors and has looked into the eyes of a leader of Los Zetas, a man called Popeye.

“I’m not afraid of anything anymore. Pain turns into bravery and courage,” she said, pausing briefly as if puzzled. “I never thought I would be the way I am now.”

Her clinic has a brown armchair, a desk, display cases and walls covered with diplomas: an odontologist’s degree and certificates from many courses. The air smells confined and stagnant, but it’s very tidy.

“It is cleaned every week,” Castro Toss explains proudly.

It is cleaned but not used.

Rosalia stopped seeing patients in her office on December 26, 2011, 48 hours after the disappearance of her son Roberto Carlos Casso Castro.

“I no longer have the physical or mental conditions to work. This is a job of precision. I had a perfectly steady hand, but my mind is already somewhere else. It’s been seven years and two months of searching and I have lost my steady hand, my nervous system is damaged,” said Castro Toss. “It is dangerous because a wrongly performed injection can leave a patient with a droopy eyelid, bad hearing or facial paralysis. Besides, I’ve lost my patience.”

She doesn’t want to work again as an odontologist but refuses to take apart her office.

“I know one day I have to get rid of all this stuff, but it still hurts. I am not prepared to give it up,” she said.

There are no bathrooms. The pay isn’t enough. The prosecutor’s office no longer provides them food. The bone searchers have the same complaints any laborer might, but they don’t say it out loud, instead they keep digging. Money is not their only motivation. The women of Solecito gather as many resources as they can and make lists for accounts payable: tools, salaries, bonuses in December.

Alejandro Vélez Salas, an anthropologist, was one of the first academics who began to investigate the violence of these years. Together with Catalan writer Lolita Bosch, he started the website Nuestra Aparente Rendición (Our Apparent Surrender), and began to publish details of the horrors. But he didn’t know about the searchers. For him, learning of them generates a contradiction: he doesn’t want any more people put in danger for trying to fill the gaps left by the absence of the state, but he is drawn to the commitment of those who aren’t direct victims.

“Bone searchers are the opposite of mercenaries. They could earn more working for the other side, participating in crime, or be part of the millions that remain indifferent, but instead they choose to do this. I find it fascinating,” he said.

“We’ve never had this kind of an experience,” said Mercedes Doretti, from the Argentine forensic team. In 50 countries, after digging graves around the world, EAAF anthropologists, archaeologists and experts had never seen bone searchers hired and paid for by the victims.

“Of course I’m worried about how the evidence is collected,” says Mercedes, relentless in methodology and protocols, her specialty. “It worries me, but I believe that family members do this because of the unwillingness or insufficiency of the state. I understand clearly why they go out, they do it because of the conditions they are in. It is a loud plea to pay attention to the State’s response, which has been insufficient so far. So far because there is an opportunity for this to change,” she said. “I hope.”

Vicente Octavio Colorado, Gerson Quevedo, Pedro Huesca, Gerardo Montiel, Arturo Figueroa and Giovanni Palmeros.

These are the people who have regained their identity thanks to the work of the bone searchers and Colectivo Solecito. Over the last three years, 12 more people have also been identified, but their names have not been released.

Eighteen bodies have been exhumed from the graves of Colinas de Santa Fe. Eighteen people who were returned to their loved ones thanks to the bone searcher.

“When we open a grave and see the bones, we say ‘Welcome to the light’,” says Lucy Díaz. “Because it is a clandestine grave, they should have never been there, nor should they have lived through the worst terror that a human being can experience. It was the last thing they saw. It sounds like fantasy perhaps, but I believe they do feel it when we say ‘Welcome. We love you here, you don’t have to suffer anymore. You are with people who love you and receive you with all the love in the world.’”

This is the only moment during a long interview when Díaz pauses to be silent.

The bone searchers and the brigade members are mediators between the living and the dead: “There is no way to be paid enough for this work, and you enter a morbid spiral as they’ve described,” said psychoanalyst Andrés Ize. And although the searchers and the brigade are the ones who remove the bodies from the land, the remains go to offices in Xalapa, the capital of Veracruz. They were allowed to enter those offices only once.

“Everything was scattered. Skulls over skulls, bones on the floor, all scattered. How can they make such a mess? It’s chaos,” Rosalia tells us, tired.

As of May of this year, the brigade has found more than 70,000 bones and 302 bodies. There are many small bone fragments. Tiny bits that, perhaps, would be the only thing a family waiting for news might ever recover.

“The Scientific Police told us that they only carry out DNA tests on skulls and long bones,” said Castro Toss.

Thousands of bones. Mountains of bones. Bones that once were people, which are still people. In the darkness.

A small spider walks across his face. Gonzalo Gómez García lifts it delicately and leaves it on the floor without getting scared or stopping the conversation.

He has no missing relatives, but in these years, his childhood friend, Edilberto Malpica Mora, was disappeared. He was also his boss.

“Has your life changed since you became part of the brigade?” we asked Gómez García.

“Too much. I have become more consistent,” he said. “I have learned to handle things and to understand what it is to lose a loved one, to not know anything about where they are.”

“How do you imagine your future?” we asked.

“If there is the option to keep on searching, I’d like to keep on doing so. Because it feels very good when a mother arrives and says ‘Thank you for finding my son.’” said Gómez García. “And because if they took me or my children, I would like people to come from their villages to look for us.”

Gómez García has a red bicycle, the only means of transport for the family. Smiling, he says that his eldest daughter is going to start college. He takes great pride in his work.

“Now I believe God gave me life for a reason.”

•

Translated by Toward Freedom. The original text was published in the Mexican monthly Gatopardo.

Paula Mónaco Felipe is a freelance journalist who works between texts and images: writes, researches and creates audiovisual production. She is a member of H.I.J.O.S., and mother of Camilo.

Wendy Selene Pérez is a Mexican freelance journalist who has worked as a reporter, digital editor, and news coordinator. She is currently working on an investigation about exhumations and mass graves in Mexico.

Miguel Tovar is a freelance journalist and photographer who has worked in national and international media. He made the photography for the documentary series Los días de Ayotzinapa (Ayotzinapa Days) (Netflix, 2019).