Somewhere in an unmarked alley of Calcutta, culture brews alongside a pot of tea at a vendor’s stall, as thick wisps of discursive politics, poetry, and para’r adda (a form of eclectic conversation intertwined with local culture, that ranges from gossip to erudite discussion) waft upwards. Close by, the last strains of the evening azaan dissipate into the dusk, in a surreal juxtaposition of symphonies, as a shaankh (conch shell) rings out to signal the birth of twilight.

Calcutta is a chaos of contradictions, where every melody, much like the azaan and the shaankh, can coexist. The soft tunes of a frail grandmother’s lullaby against a backdrop of jarring taxi horns, the passionate cries of a student-led protest against a complacent rickshaw-walla’s snore on a sultry August afternoon. Calcutta, for its residents, is a bumbling, bustling Indian metropolis known for having a diverse soul.

Yet, for all that Calcutta stands for, for all the eulogies sung by expats and locals alike, the love that the city fosters in each being is shadowed by an undercurrent of contradictions. Communal harmony is one of the blessings that the city supposedly bestows; yet those who suffer from mental illness are begrudgingly acknowledged at best, if at all.

Of all the socioeconomic cohorts that Calcutta is home to, the privilege of receiving mental health treatment belongs only to a select few. Even among those who can afford it, many remain unaware of their needs or the possibilities for help.

Mental illness has long been shrouded by stigma, across cultures, only finding more mainstream recognition recently, owing to the rising global tally of neuropsychological disorders. In India, mental health awareness continues to stagnate in a haze of confusion and ignorance. Casual conversations among urban, educated circles reflect an alarming lack of awareness.

Calcutta’s culture entails a veiled conservatism that clashes with the progressive ideals of the people. Idiosyncrasy typifies the larger population: our sensibilities are a stark departure from the parochiality of previous generations, yet retain relics of the latter.

This is especially palpable in the narrative exemplified by a mental health professional I interviewed last year, who said “…I understand to an extent that [mental health concerns] need to be addressed professionally –and people around you think that it is not real because it cannot be seen– it is very difficult to say that you want actual treatment for something that has no x-ray plate or blood report saying that you’re depressed.”

The interplay of age-established traditional ideals with relatively radical thought can lead to a kind of dissonance, where many social issues remain in a confused ideological limbo.

While Calcutta’s budding population of progressive mental health advocates ensure some discussion of pressing concerns, dominant socio-political ideals that have long since become obsolete elsewhere still colour the collective mindset of many in the city. It is not unusual to overhear comments such as “You’re not depressed, you’re just sad,” or “Go out for a walk, you’ll feel better,” or “I don’t know why you are creating a mountain out of a molehill.”

Statements like these, so flagrantly simplistic that they trespass into the ludicrous, shape the mental health options of countless individuals in a country where pervasive stigma and stereotypes continue reducing mental health to a taboo.

India and Mental Health

According to a study by the World Health Organization, one in seven Indians face challenges to their mental well-being. Approximately 13 million people in West Bengal (of which Calcutta is the capital) suffer from mental-health problems that require immediate attention, with the prevalence of disorders such as depression and anxiety being 13.5 percent in urban centres and 6.9 percent in rural districts.

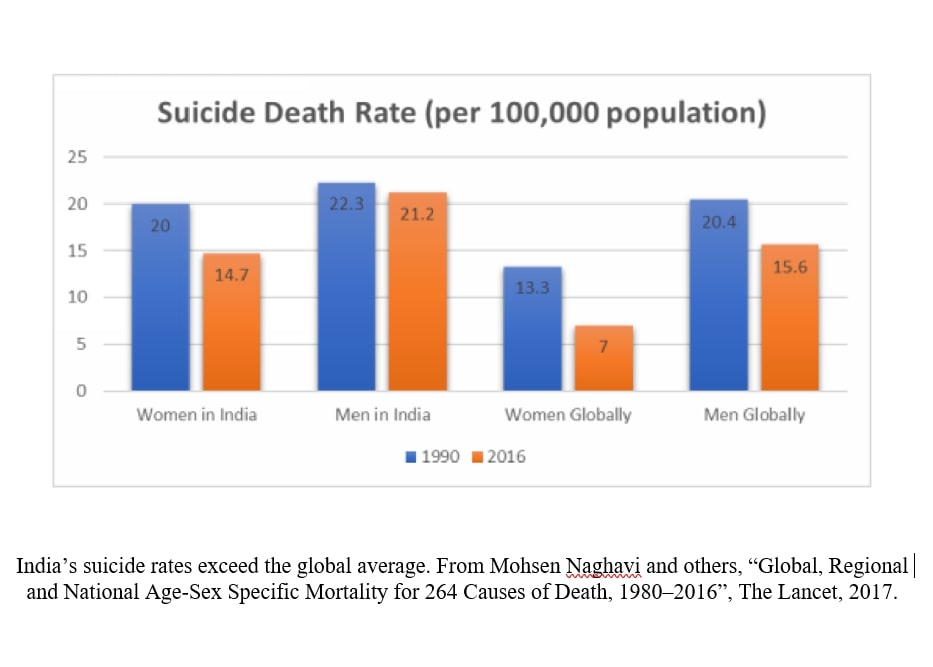

On a global scale, India accounts for 28 percent of suicides worldwide, with West Bengal being among the top three states contributing to suicides in the country. As a socio-medical issue, suicide receives little attention and remains under-reported, owing in part to the stigmatization of mental health. Religious, political and economic issues contribute to India’s avoidance of the root causes of suicide.

Glaring gaps compound the issue of mental health in India, ranging from lack of awareness and accessibility of care to a dire shortage of trained mental health professionals, inadequate funding, and low prioritization within the healthcare budget. With fewer than two psychiatrists per 100,000 people, it is imperative that mental health awareness, accessibility, and affordability is addressed. However, obstructions run deeper than just logistics or finance.

A survey of 3,556 respondents from eight cities across India, conducted by non-profit The Live Love Laugh Foundation (TLLLF) evinced a staggering 47 percent who could be categorized as being highly judgmental of people perceived as having a mental illness. These respondents were more likely to claim that a safe distance should be maintained from those who are depressed, or that interacting with people with mental health concerns could affect the mental health of others. The cohorts mired by such stigma generally belonged to a higher socio-economic and more educated populace.

Despite the challenges, there has been progress. The most significant breakthrough was achieved with the 2017 Indian Mental Healthcare Act, which mandates the right to adequate treatment for citizens and decriminalizes suicide. But change at the national level does not always translate into change at regional and local levels. A 2016 study showed that the urban population in Calcutta continues to bear a high level of discrimination towards people with mental illnesses, in comparison to those from other cities.

Rising awareness can allow for early recognition, access to treatment, and adoption of preventive measures, as well as enabling advocacy, leveraging of political will and funding, especially within the not-for-profit sector.

In Calcutta today, mental health literacy in every strata of society is urgently needed for social change. Community engagement, especially that facilitated by non-governmental organizations, could help create a pathway to a society more tolerant towards those dealing with mental illness.

This article is the fifth produced in collaboration between Toward Freedom and the Symbiosis School for Liberal Arts in Pune, Maharashtra, India. For more information, contact Barry Rodrigue <[email protected]> at Symbiosis International University.

Author Bio:

Roshni Mukherjee is from Calcutta. She is a graduate of Symbiosis International University (Pune, India), with a degree in Psychology from Symbiosis School for Liberal Arts.