DELHI, India—Rohit Sharma stood on the spot where, more than a fortnight ago, he had a bed in a night shelter. After having traveled more than 650 miles from his home city of Patna, Sharma lived for the past four years in a shelter the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) had provided.

“I used to get picked up from here for work. I would then come back and sleep here. This was my home,” said Sharma, who works in the tent-fitting industry. “Most of us fix tents or work for caterers for different occasions, like marriage or religious programs.”

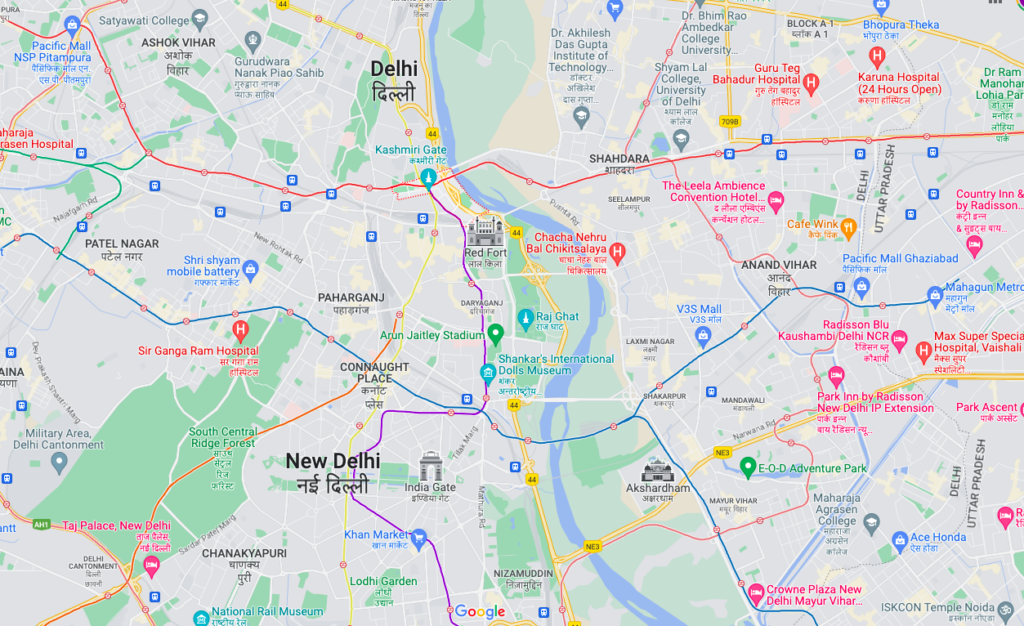

Yet, everything changed on the night of March 9. That’s when bulldozers, in the presence of police, demolished temporary shelters, according to homeless people like Sharma. Now, he, along with about 1,200 people who used to live in four night shelters, sit under the sky. The site of the former shelter is close to the interstate bus terminus (ISBT) at Kashmere Gate, the northern entrance to the historic walled city of Old Delhi.

Displacing the Poor Ahead of G20 Summit

Activists and the affected said current demolitions are part of preparations for the Group of Twenty (G20) Summit that the capital city of New Delhi is preparing to host in September. G20 is an intergovernmental group made up of 19 countries plus the European Union. Altogether, the G20 represents two-thirds of the world’s population. Its stated aim is to address global economic issues. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi became its chairman last year.

Past G20 summits had been met with protests from both anti-globalization movements and groups opposing the displacement of society’s poorest to make way for a summit venue. Such was the case in 2010 in Toronto, Canada, and in 2017 in Hamburg, Germany, for example.

Similarly, before Donald Trump visited India in 2020 as the president of the United States, the huts of poor families were demolished around the venue to host him in Gujarat state in western India.

Estimates of 100,000 to more than 300,000 people live in Yamuna Pushta, where India’s largest reported slum developed in flood-prone conditions along the banks of the Yamuna River flowing through Delhi, India’s National Capital Territory (NCT).

Destroying Livelihoods

Since the demolition drive in Delhi began, poor and working-class people said police have been trying to ensure they do not linger in the area where they normally wait to secure gigs for the day.

“They take us in a bus forcefully and drop us at a distance from here and ask us not to come back,” Sharma said, adding, “We find work at this place. Contractors come here and pick us up from here. Where else would we find work?”

The location to which homeless people must be moved is supposed to be “close to where they are concentrated and close to the work site as far as practicable,” as per Indian Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs’ Revised Operational Guidelines for Scheme of Shelter for Urban Homeless under Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Urban Livelihood Mission (DAY-NULM).

However, the affected said they will struggle to find work after being forced to move.

“I have been working for the cause of the homeless for more than 20 years now. Governments never rehabilitate any homeless, like they claim to do,” alleged social activist Sunil Kumar Aledia, who is National Convenor for Homeless Housing Rights (NFHHR).

Bulldozing Homes

Aledia filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court of India on March 3.

“We approached the Supreme Court as the demolition drive was going on in other places, and we did not want other temporary shelters to be demolished,” Aledia said.

But, before the court could take up the matter, Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) razed the shelters.

“We were sleeping when the authorities came with bulldozers. They did not tell us the reason for demolishing our home,” Sharma told Toward Freedom. “Some of the inhabitants were manhandled by the police.”

Little information is available about the source of the demolition drive. NCT Urban Development Minister Saurabh Bharadwaj wrote to DUSIB on March 16, inquiring under whose direction the action was taken. The letter that the Times of India obtained stated:

“Director DUSIB has given a statement in the social media that the demolition has been carried out on the orders of Govt. of NCT, Delhi. DUSIB may kindly specify who in Delhi Govt. has given these directions? And whether these orders were recorded or merely oral?”

DUSIB remains mum.

“The matter is sub judice in the Supreme Court, and it wouldn’t be appropriate to comment at this stage,” P.K. Jha, an official of DUSIB, told Toward Freedom. Sub judice describes a matter under a court’s consideration and, therefore, official commentary is prohibited.

‘We Only Need Food and a Make-Do Shelter’

“Some big event is going to take place here. That’s why they broke this shelter,” said Arun Kumar Jha, another occupant of the night shelter, sitting on the footpath across the road. He frequents different night shelters in the area.

Dozens of homeless still sit in the place where their shelter was until a few weeks ago. They have always relied on voluntary organizations, temples and individuals for food. Across the road, approximately 300 meters (328 yards) away from the shelter is a revered Hanuman Temple. Hanuman is a Hindu god with the face of a monkey known for his devotion via service. The homeless crowd outside the temple has increased after the demolition. They find it easier to find food and money from worshippers visiting the temple.

“Food is not a problem here, many people come and serve us, that’s why we (homeless) do not want to leave this place. We only need food and a make-do shelter,” Jha told Toward Freedom. “Government takes us in a bus from here, but never provides food.”

Parva Dubey is a freelance writer based in New Delhi. Parva can be followed on Twitter at @ParvaDubey.

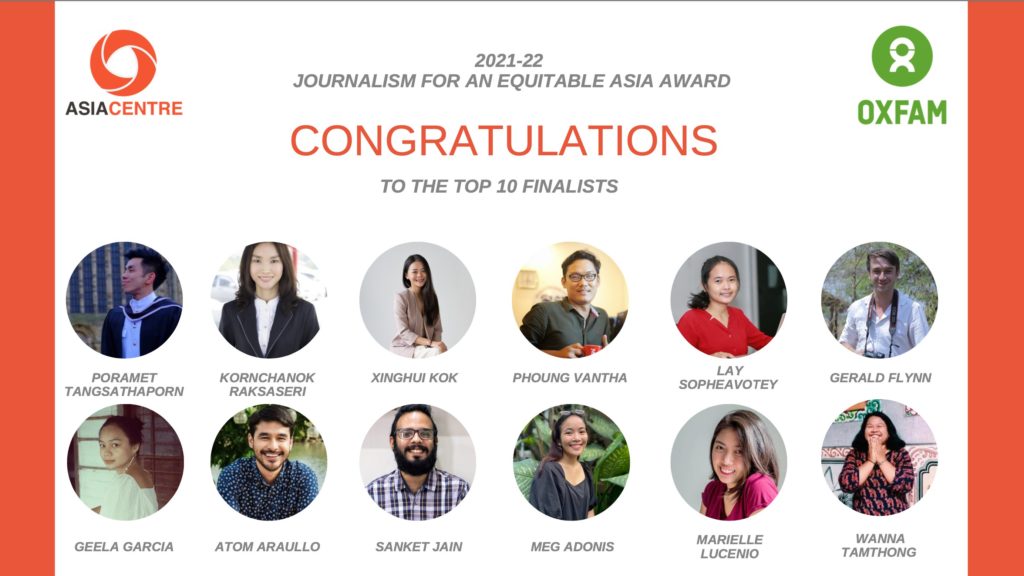

The award winner will be announced at 2 p.m. Bangkok time on March 15. The event can be attended in person and watched online by registering

The award winner will be announced at 2 p.m. Bangkok time on March 15. The event can be attended in person and watched online by registering