It’s 5 pm and violently raining as I write, sheltered comfortably in my South Kolkata apartment. Evening rains are not uncommon. From late June until early October, southeast monsoon winds traverse the state of West Bengal, though owing to climate change, storms can now be experienced as early as May. In fact, on May 20th, cyclone Amphan struck our homes. It was the worst tempest to hit East India since 1737.

Amphan brought widespread havoc to almost all of West Bengal and Odisha as well as parts of Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Sri Lanka. There were 86 reported casualties in West Bengal, mostly caused by electrocution or homes collapsing. Outside of Kolkata, rural areas experienced even greater wreckage – acres and acres of farmland in the Sundarbans were submerged by massive floods. Death and destruction also spread to the Paraganas and Orissa, leaving four dead and over 500 homes destroyed.

Even as the raging cyclone took away homes and lives, national media coverage was offhand and perfunctory. Even the governor of West Bengal minimized the effects. Strikingly, his apathetic statements were broadcast, while the horrific impact of the storm was hidden from the world. Mainstream Indian media were more occupied with discussing the 29th anniversary of former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s death and various celebrities’ quarantining for the COVID-19 lockdown.

The primary source of accurate coverage of Amphan was found on social media, including WhatsApp and Twitter. While the reliability of such sources is constantly questioned, what should really be questioned is India’s increasingly negligent national media.

Indian Media’s Distorted View

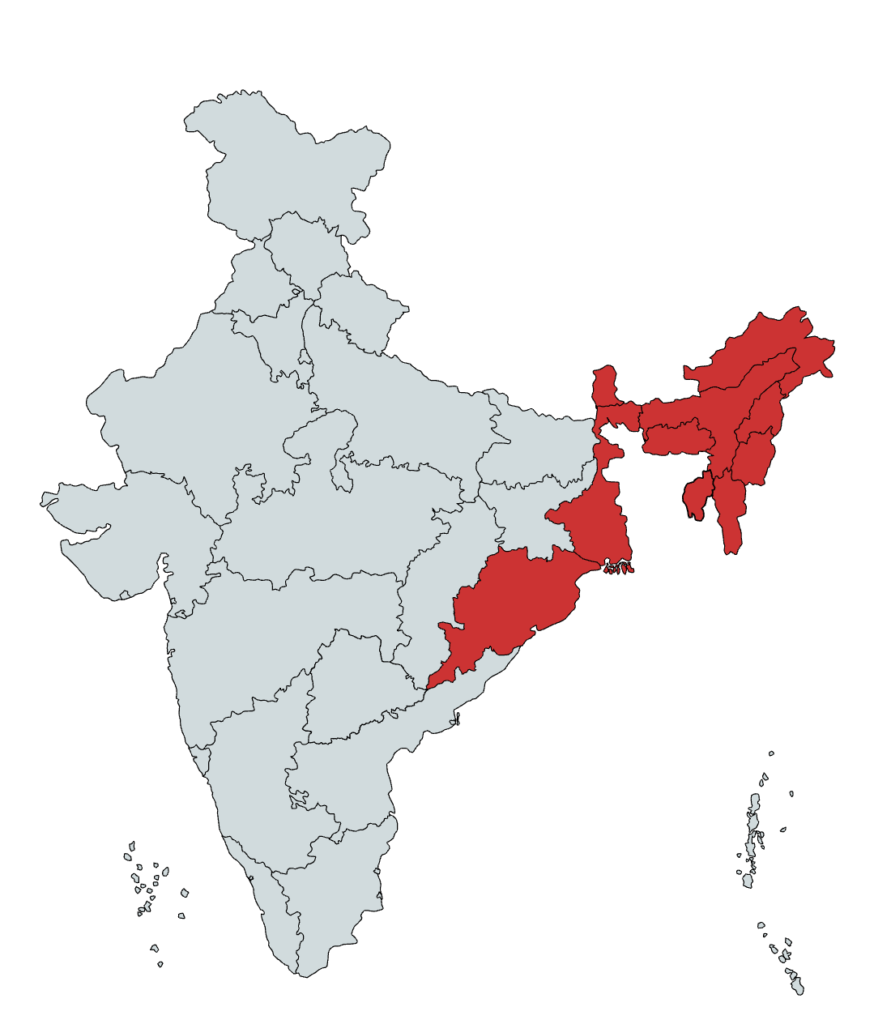

The collective indifference of the media toward eastern India in the wake of Amphan demonstrates what the North East has been facing since 1947, in the wake of the creation of the Indian nation itself. ‘North East India’ comprises eight states: Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura, with a total population of approximately 45 million.

It forms about 3.76 percent of India’s entire population. The Indian government has historically looked at the complex tribal and territorial issues of the North East as a political irritation that needed suppression instead of resolution. This has aggravated territorial disputes and led to under-development. The Indian media has pursued this lead and consistently trivialized the northeast.

While news from New Delhi or Maharashtra is breathlessly covered, India’s northeast finds itself in a black box of isolation and misrepresentation. The fact that all distinct states are clubbed together as the North East in the first place is a result of a colonial practice for the ease of identifying a geographical section. The media’s adoption of this practice takes away from the focus each state deserves. Furthermore, the North East is often viewed through a myopic lens of insurgency and divisive politics.

A striking example of this is the media’s portrayal of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). To subdue ethnic and territorial autonomy, the Indian government institutionalized paramilitary forces in the North East in 1958. However, AFSPA has been accused of orchestrating violence in the region. Human Rights Watch declared AFSPA as a “tool of state abuse” and asked the government to repeal it. The international media such as Al Jazeera and BBC World News have covered military violence in North East India, but the Indian national media has avoided documenting it.

National media tends cover only dire and sensational happenings, such as the Manorama Devi Rape Case. Thangjam Manorama was raped and killed by military personnel in her hometown in the state of Manipur on 11th July 2004. Soon after military involvement was suspected, military personnel denied the rape charges. Both the central and state governments failed to hold the accused accountable. Protests followed in Manipur and adjoining states, wherein women marched naked in the streets holding banners that read “Indian Army Rapes Us.” Mainstream media reportage probably would not have existed had it not been for such a monumental protest.

Media coverage should represent every nook and corner, especially the margins, but it does not. Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky discuss selective representation in their celebrated 1988 book Manufacturing Consent, in which they describe how traditional media acts as a model of propaganda. Widely touted as the fourth arm of governance, mainstream media actually serves its own profit, an owners’ profit, and the profit of those in a societal hierarchy. Thus, margins akin to North East India are caught in a spiral of silence and distortion.

Rising Alternate Media

However, many emerging, independent forums are causing a break in the exclusive grid created by mainstream media. These platforms are actively reporting news from the margins, aided by sufficient press freedom that mainstream media lacks.

For example, the NewsLaundry, an online news and media outlet founded in 2012, published an article on cyclone Amphan titled ‘Remains Of The Day’ that described the storm’s impact with examples of how it affected residents. Other online platforms in India, such as The Quint, founded in 2015, or The Print founded in 2017 by journalist Shekhar Gupta, publish articles on events brushed aside by the national media. Their efforts expose the contradictions of India’s media and the extent of marginalization that eastern India faces.

NewsLaundry has published stories on the North East and COVID-19, and published revealing conversations about how North Easterners face structural racism. This is a major shift from how mainstream media has focused on just a discourse of insurgency.

The Hoot, an Ashoka University initiative started in 2002, aims to be a research-based archival online media forum that largely focuses on free speech and media ethics within the subcontinent. It published ‘Coverage of the North East Declines’, which statistically examines mainstream media’s neglect of the region. The study revealed that between 2012 and 2013, national mainstream media’s coverage of the North East declined by nearly one third.

The sample for the study included four recognized Indian English dailies, namely, Times of India, The Hindu, Hindustan Times and Indian Express. Additionally, reportage was extremely selective, there was no parity in representation of all eight North Eastern states – it was found that all four dailies mostly covered news from Assam (70 percent) over two years.

Freedom of the press has long been a matter of debate within India and beyond. India’s once celebrated press was instrumental in shaping public opinion during the independence movement and the building of the nation, but it has undergone many changes, and not for the better. The government has imposed strict sedition and defamation laws on the national media; originating from Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code in 1870 – which have been misused since the 1960s onwards in modern India.

Freedom of Speech (Article 19A of the Indian Constitution) which Freedom of Press falls under, is a fundamental right. However, free speech in India has been severely limited, so much so that it is close to a mythical concept now. Any form of dissent in modern day India is considered sedition and is often punishable.

In 1988, the government banned Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses and Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History arguing blasphemy against Hinduism. In addition to banning texts, students were arrested and detained on grounds of protesting against the unconstitutional Citizenship Amendment Act (2019).

By virtue of the Telegraph Act (1885), the Cable and Television Network Regulation Act (1995), the Censor Board and the Sedition Law in place, the Indian government oversees all kinds of media. The misuse of these restrictive laws manifests in mainstream media’s representation of political issues. In much of the media, protests, movements and dissent is criticized while the government agenda is glorified. Most of the reputed media houses are now used as a propaganda apparatus by politicians and industrialists.

In general, the mainstream media in India ignore issues of minorities: farmers, Dalits, the transgender community, and women. It is safe to say that, in the current scenario, most of the media is most concerned with lucrative pay from their advertisers, funders, and the politicians in power. Thus, it is essential for the incarnation of alternate media platforms in India to focus on areas that have been historically neglected.

The issue of accurate and critical information is crucial in communicating how climate change is an inevitable and inescapable phenomenon that threatens all of mankind. In this context, accurate news of cyclone Amphan is relevant both nationally and globally. It was Indian mainstream media’s duty to dignify Amphan with adequate coverage.

The neglect that mainstream media has shown towards East India and has continually shown towards North East India are examples of the dying effectiveness of such media platforms. Today, it is alternative independent media platforms that play a significant role in bringing about a positive change in the nation.

This article is the fourth produced in collaboration between Toward Freedom and the Symbiosis School for Liberal Arts in Pune, Maharashtra, India. For more information, contact Barry Rodrigue <[email protected]> at Symbiosis International University.

Author Bio

Amarabati Bhattacharyya is a fourth-year student at Symbiosis International University in Media Studies / International Relations at the Symbiosis School for Liberal Arts in Pune, Maharashtra. She has worked with and interned for the Indian newspapers, The Hindu and The Telegraph, over the past three years.