It was the last leg of First World War when demobilized Indian troops, anxious to return home from the trenches of Europe, reached the port of colonial Bombay on May 29, 1918. The city was known for facilitating a glut of movement across its waters, making it easy for the H1N1 influenza virus that arrived with the war veterans to remain discreet for more than 48 hours. On June 10th, the police sepoys posted at the docks were diagnosed with India’s first cases of the highly infectious flu, which we now know as the Spanish Flu.

A pawn in the colonial regime at the time, India was swept with a wave of casualties. The approximate average mortality rate of the flu across the world was 2.5 per cent, whereas in India it climbed to almost 6.9 per cent, causing an estimated 18 million casualties. The British had little interest in developing the healthcare infrastructure in the country, which played a key role in creating the disparity. Indian-grown food was continuously exported, and doctors were sent from India to Britain to supply war efforts. This caused a nation-wide spell of hunger, which weakened the peoples’ immune systems, making Indians even more susceptible to the virus. As a British colony, India could neither provide nor offer access to basic legal rights to its people to stay alive.

Today, India is the largest democracy in the world, and much has changed since the days of the Spanish flu. As the coronavirus pandemic spreads around the world, it is interesting to consider in which ways India is moving to prevent history from repeating itself.

On the evening of March 25th, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared a twenty-one-day lockdown starting at midnight. Surprised at such short notice, people responded with panic and ended up crowding markets around cities to stock up before midnight.

On April 14th, Modi extended the initial three-week lockdown by 19 more days, continuing a near complete restriction of movement and shutting all non-essential commercial, private and government establishments, all industries, transport by air, rail and road, hospitality services, educational institutions, places of worship, and political gatherings.

From a legal perspective, India is a parliamentary democracy that functions within the framework of a written Constitution, and its judicial courts have the authority to review legislative and executive actions. At the central level, the legislation India has opted for is the National Disaster Management Act, 2005.

But a natural disaster act isn’t equipped to deal with a wide-spread pandemic: for instance one of its provisions states that for the act to apply, specific areas of the country need to be declared as disaster-hit. Further, the 2005 Act fosters a top down approach that gives the federal government overriding powers of execution over state governments, despite the fact that under the Indian Constitution public health is managed at the state level.

There is no denying that directing a population of 1.3 billion is more daunting a task than meets the eye. An attempt was made by states to deal with the situation by invoking the 1897 Epidemic Diseases Act (EDA) before the declaration of a nationwide lockdown. This resulted in a confrontation between the states and an archaic British rule in the face of an independently written constitution.

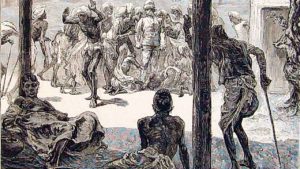

EDA was enacted to prevent the spread of the plague, a bacteria-led pandemic (1896-1939), from Asia to Europe. It promoted direct and forceful intervention in the lives of people, such as home invasions by troops, physical inspections, and burning of private property as part of mass sanitary measures. At the time, Indians intensely criticized the measures taken behind the mask of legislation. However, despite such history of disapproval, EDA still continues to be enacted at the state level.

Regarding the movement of people, Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 currently prohibits more than five people from assembling in public places. A collector, a district level chief executive responsible for revenue collection, has been declared as the “incident commander” in each district. The collectors have been equipped with exclusive power to issue exception passes to certain journalists, doctors, healthcare workers etc. Movement of individuals is completely constrained without the grant of a special government-issued pass.

The dovetailing of all these decrees has laid bare the ambiguous, open-ended character of the statutes, which are backed by unchecked sweeping powers of the federal and state governments. The measures undertaken so far, and the imprecise guidelines issued, have unabashedly infringed on legal and fundamental rights. Police in some states have started physically “stamping” people on prominent parts of their bodies to shame them into staying at home during lockdown.

The government recently rolled out a COVID-19 “tracking” application called Aarogya Setu for Android and iphone users. The app uses geographical data and Bluetooth to analyze the proximity of users to COVID-19 positive patients. The app intends to “notify, trace, and suitably support” registered users regarding the coronavirus. However, without a statutory standard governing data collection and processing, the use of mobile applications to track quarantined individuals or to issue passes for individual movement, is concerning.

My aim is not to condemn the necessity of lockdown, but rather to understand it in the light of proportionality, rationality, legality, and most importantly equality. The government of the state of Karnataka released a requirement of hourly “selfies,” which can act as proof of quarantine; but the same state failed to hold its former Chief Minister accountable for occasioning a gathering of more than one hundred people for the wedding of his son on the twenty-fourth day of lockdown.

The revival of these old statutes has led to confusion and chaos, which the wealthy can escape by taking advantage of the loopholes. During the outbreak of the Spanish Flu in 1918, 61 lower caste Hindus died per thousand, 18.9 upper caste Hindus died per thousand, compared to merely 8.3 per thousand Europeans living in India. Perhaps the aim of the colonial, hierarchical legislation at the time was to achieve these very numbers.

In the words of Prime Minister Modi, “a government today is one that thinks and hears the voice of the poor.” To this end, a comprehensive $22 billion relief package has been announced by the government through direct cash transfers and food security measures aimed at salvaging the situation of millions of poor hit by lockdown.

Although the move is commendable, the contrast between century old needs and modern needs must be highlighted. If access to food, shelter, and health facilities all are essential requirements, then protection of freedom, life, and equality are fundamental in 21st Century. The legal system claims to protect the rights of the poor, to uphold the dignity of marginalized, and to maintain parity in society. Hence, there is an ardent need to secure legislation that meets the needs of independent Indian citizens, who value their lives and freedoms.

The lockdown has imposed direct restrictions on the rights to free movement and peaceful assembly, and indirectly on the rights to livelihood, life, and personal liberty guaranteed under the Constitution. The fundamental validation of such restrictions lies under Article 19(5) of the Constitution, which permits such measures in the interest of the general public. In India, a law preceding the Republic Day of 1950 may survive only if it passes the constitutionality test.

The 133-year-old EDA has not yet been subjected to this test; hence, its guidelines suggest a straight jacket, one size fits all formula which has led to imposition of restrictions without any regard to proportionality, which is the idea that an individual must not be subjected to greater hardship than is absolutely necessary.

Migrant workers stripped of their daily wages during lockdown have been economically hit the hardest. Despite sealed borders and absence of public transportation, many decided to undertake weeks-long journeys on foot to reach their rural hometowns. Officials and some residents unreasonably declared them violators, forgetting that being on the right side of the law is a luxury not many can afford. Restrictions resulting in such major economic collapse ought not be imposed without taking into consideration the socio-economic status of the most vulnerable in society.

Every pandemic is unique. Hence, one of the most essential elements to fight COVID-19 lies in framing new legislation that not only meet current public health needs, but also that secures a just and competent legal framework to handle the pandemic.

On April 22nd, the government amended the EDA for the first-time, with a one-page act that imposes a seven-year jail penalty for inflicting violence upon health workers. The move came in response to public pressure. However, the statutes still fall short in providing a legal framework to regulate the availability and dissemination of vaccines and drugs, and to implement response measures. The statutes are also silent on observance of principles of human rights during implementation of severe measures undertaken. As discussed in instances above, these statutes have failed to uphold the right to equality, to dignity, and to life.

The pandemic of 1918 proved to be a major turning point in the history of the freedom movement in India. Instead of posing as a threat that might travel from east to west, the virus had come from the frontiers of west itself. The colonial regime quickly lost interest in containing the spread, hence, people-run voluntary organizations like the Social Service League and Ramakrishna Mission stepped in to supply medicine and food.

This resulted in a community building exercise, wherein people turned to one another for comfort in the face of discriminatory laws, fuelling the independence movement. A product of the Colonial British Regime, the Epidemic Diseases Act has sanctioned the modern democratic government today to shift its burden of securing a social order based on equality as stated under Article 38 of the constitution, on citizens.

If the government today continues to enact blanket guidelines and restrictions without regards to proportionality or equality, it is inviting history to repeat itself. Arbitrary guidelines, discriminating laws, prejudiced implementation favouring the rich, together form the perfect storm for massive backlash, which can have great societal repercussions.

The Indian government must draft a statute that creates specific functions for primary, secondary and tertiary responders, and which contains the procedure and structure to deal with national health emergencies. Conforming with the system of checks and balances, this statue must establish clearly defined responsibilities, leaving no scope for violations of standards of proportionality.

This article is the first produced in collaboration between Toward Freedom and the Symbiosis School for Liberal Arts in Pune, Maharashtra, India. For more information, contact Barry Rodrigue <[email protected]> at Symbiosis International University.

Author Bio

Tanushree Ajmera is currently studying law at Symbiosis Law School, in Pune, India.