The conflict between Palestine and Israel has been raging officially for more than seven decades, making it the world’s longest-running dispute.

Jordan’s domestic and foreign policies have been affected because it shares its border with occupied Palestine and the state of Israel. However, it is clear based on recent occurrences that the landlocked country is playing an increasingly insignificant role in the dispute, even though the peace process would be incomplete without the kingdom’s input. In fact, until the 1970s, Jordan was an indispensable player, having hosted thousands of Palestinian refugees. Jordan seems to be trapped by its own security restrictions and has largely ceded the peace process to its rivals, including Egypt.

Earlier this year, during the 11-day war in Gaza, U.S. President Joe Biden spoke twice with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Meanwhile, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris once telephoned Jordan’s King Abdullah.

Jordan also reacted late to the crisis in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in Jerusalem. For example, Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Al-Safadi took two weeks to respond to the escalating conflict between the Palestinians and the Israelis. The response came in a tweet. Later, when he met with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, he only repeated his warnings that “Jerusalem was a red line” and that “Israel was playing with fire.”

Jordan and Egypt play a zero-sum game in the Arab-Israeli peace process. But in recent years, Amman has lost its historic role to Cairo. Cairo mediated between Israel and Hamas in the last Gaza war in 2014. Then in 2017, Cairo mediated a ceasefire between the two Palestinian groups, Hamas and Fatah. Egypt also was active in the prisoner exchange between Palestine and Israel in 2006. Then Egypt sought an immediate ceasefire in the last Gaza war in May. Al-Sisi ordered the opening of the Rafah crossing between Egypt and occupied Palestine, so injured Palestinians could be treated at Egyptian hospitals. The Egyptian government sent mediation teams to Hamas and Israel, intending to send fuel to Hamas’ only power plant. Al-Sisi also allocated $500 million for the reconstruction of Gaza.

Cold Peace

Jordan’s declining role in the Palestinian peace process boils down to a number of reasons. For instance, Jordan’s relationship with Israel has reached its lowest point in recent years. During Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s time in office, King Abdullah did not speak or meet with him.

But it was Israel’s plan to annex parts of the Jordan Valley and the West Bank that became the greatest factor in reducing relations between the two countries. Netanyahu’s aim with the annexation plan was to reduce the economic impact of Covid-19 inside the country and the instability in the unity government. The plan was introduced as part of the so-called “Deal of the Century” U.S. President Donald Trump had touted. Israel’s annexation plan probably was aimed at putting to rest Israel’s dream over the past few decades of occupying from the Nile River to the Euphrates River. Occupying parts of the West Bank would increase Israeli territory and would help snuff out the Palestinian liberation struggle in the West Bank.

It seems Palestinians in the West Bank are likely to change their demand from a “two-state” solution to obtaining equal rights with Israeli citizens, thereby strengthening the “one-state” solution. In the latter case, Palestinians would live side by side with Israelis, instead of under military rule. However, Jordan worries Israel will probably try to force Jordan to accept responsibility for Palestinian refugees in Jordan, as well as the Palestinians displaced by the annexation plan.

Bitter incidents have occurred in recent decades between Israel and Jordan, such as the 1997 assassination of Hamas leader Khaled Mashaal on Jordanian soil that King Abdullah was unaware of, and the shooting of the Israeli embassy guard in Amman in 2017, which Jordan considers a murder. King Abdullah has expressed hopes relations with Israel’s new government under Prime Minister Naftali Bennett will improve, so the turmoil can end. Bennett’s secret visit to Jordan, followed by the sale of water and a trade agreement between the two countries, raised hopes of improved relations. But it should not be forgotten Bennett opposes the two-state solution. In addition, the opposition in Israel—including Netanyahu—have criticized the new Israeli government. Bennett’s government and his cabinet appear afraid Netanyahu will return to power, and that is why they have been struggling to show this government is more efficient and assertive than Netanyahu’s governance of 12 years. Therefore, it is unlikely the new Israeli government will recognize Jordan’s concerns and open a place in its foreign policy to resolve its differences with the Palestinians, as Jordan has indicated it would like.

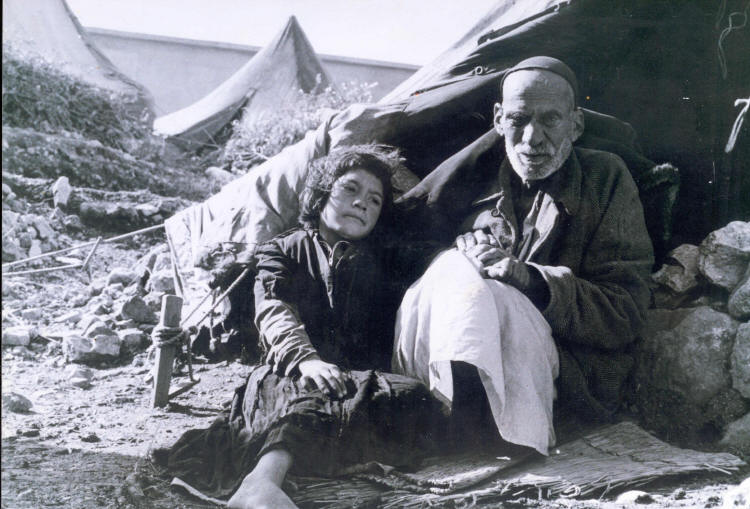

Forgotten Palestinian refugees

The relationship with the United States and its particular attitude toward the peace process are another reason why Jordan has lost weight in the dispute. Jordan opposed Trump’s “Deal of the Century” because it did not address the issue of Palestinian refugees.

Trump may have left the White House and his “Deal of the Century” may have been forgotten, but the deal has made a long-term impact on Jordan’s security. The plan is in Israel’s interest, as Tel Aviv rejects the right of Palestinians to form a state in the West Bank and gives Jordan weight as an alternative to Palestinian refugees. Trump’s plan allowed the 2.5 million Palestinian refugees living in Jordan to settle permanently in the kingdom, and that is Jordan’s red line.

A close race is underway to increase the role of nations in the peace process. Jordan must re-double its efforts so that it does not lag behind other Arab countries. While Egypt considers the Gaza Strip as it plans its security, Jordan must emphasize the role of the West Bank in its national security. Jordan currently has no ties to Hamas after expelling the group in 1999 for fear of the Muslim Brotherhood infiltrating the country. Meanwhile, Egypt, despite ideological differences, contacted Hamas and was able to use its influence in the 11-day Gaza ceasefire.

Jordan needs to better understand the geopolitical realities of the region and improve its relations with other countries, such as Iran, Turkey, Iraq and Syria, so it can renew its capabilities in the long-standing conflict.

Dr. Mohammad Salami holds a Ph.D. in international relations. He is a specialist in Middle Eastern policy, particularly that of Syria, Iran, Yemen and the Persian Gulf region. His areas of expertise include politics and governance, security and counterterrorism. Dr. Salami is an analyst and columnist for various media outlets. He can be followed on Twitter at @moh_salami and he can be reached via email at [email protected].