Correction: The majority of homes to be razed were built after 1967. A previous version of this article stated otherwise.

EAST JERUSALEM—For the fifth week in a row, residents of Jabal al-Mukaber, a Palestinian neighborhood in Occupied East Jerusalem, demonstrated outside city hall against a municipal plan to demolish their homes.

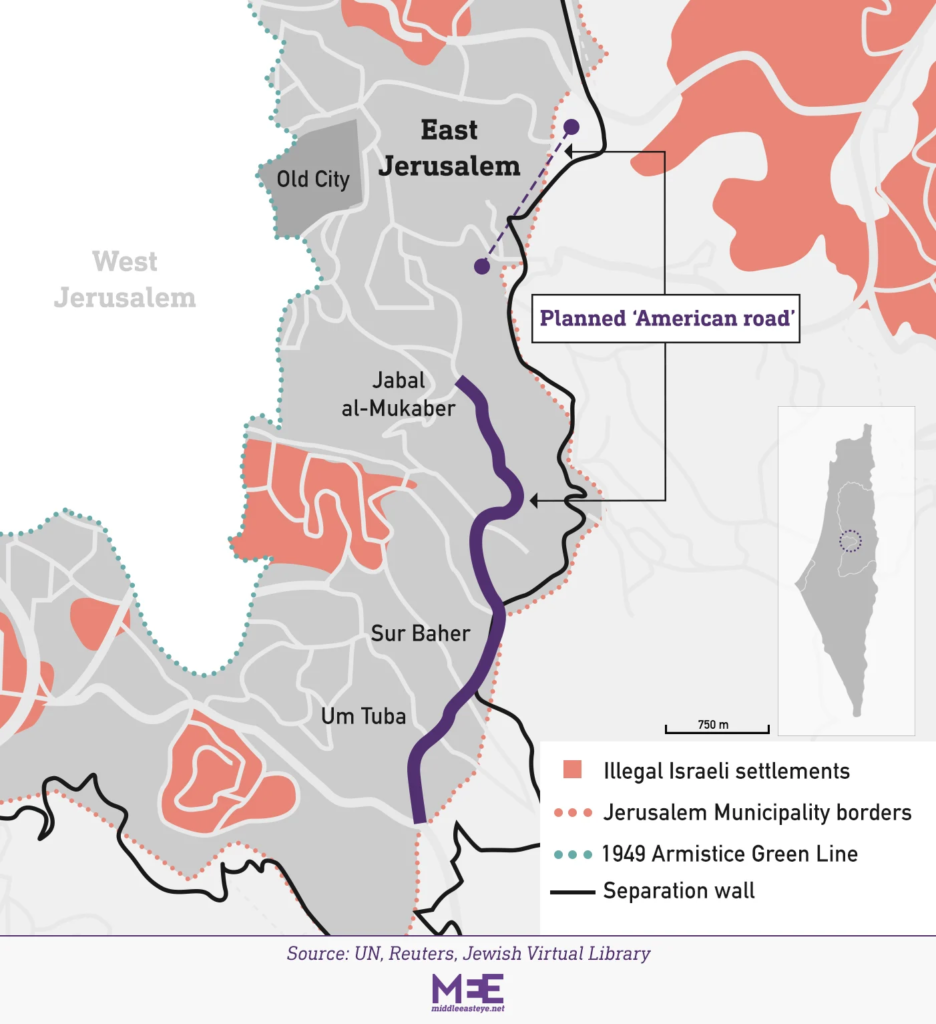

Banging drums, blaring fog horns and blowing whistles, protesters demanded on March 20 that the municipality freeze 62 home demolition orders. Residents received these notices in January as part of a plan to expand the American Road, a highway cutting through Jabal al-Mukaber and largely viewed as a bypass serving illegal Israeli settlements throughout Jerusalem.

“This is a political target by the municipality to push the residents of Jabal al-Mukaber to take their stuff and live outside of Jerusalem,” said Mohamed Nas, who received a demolition order.

East Jerusalem’s ‘Urban Renewal’ Plan

The American Road was first proposed in 1996. It is named after a much narrower road U.S. contractors had abandoned midway through construction because the Six-Day War had begun in 1967. By the 2019, plans were underway to turn the rural road into an urban highway. The latest $250 million construction began in 2020.

The American Road recently was widened by 52 feet. But now plans are underway to expand the highway by another 105 feet, where the 62 houses slated for demolition are located.

An estimated 800 housing units also are being threatened with demolition to develop both sides of the highway, mostly for commercial and office use.

Sari Kronish, an architect with Israeli planning rights organization Bimkom, explained the municipality is hoping to turn the area around the American Road into an urban center. But without an adequate proportion reserved for residential use, the municipality’s urban renewal scheme fails in addressing the neighborhood’s main issue—a lack of housing.

“Equitable housing solutions are what drive the market,” Kronish said. “If we compare it to other places in the country, you have a minimum of 50 percent housing here.”

According to Kronish, residential building rights are included in this development plan, but do not allow for legalizing existing homes. Therefore, the houses in Jabal al-Mukaber will need to be razed and rebuilt into 8-floor units to meet the municipality’s new standards.

While only 62 homes in Jabal al-Mukaber have received official demolition orders, residents say municipal building plans suggest a total of 862 homes on about 94 acres are at risk of demolition because of the highway’s outlined development and proposed commercial center.

“Projects of urban renewal and evacuation and construction are being led, in cooperation and in dialogue with the residents,” said a municipality spokesperson, referencing reaching a joint compromise with the Bashir family in Jabal al-Mukaber.

However, the municipality did not respond when asked to elaborate on this agreement. Nas said any proposed settlements in Jabal al-Mukaber are false.

Denying the Right to Build

In a statement to Toward Freedom, the municipality said they will not permit illegal construction in the city. The majority of homes in Jabal al-Mukaber, and throughout East Jerusalem, lack building permits.

According to Jerusalem municipality data obtained by settlement watchdog group, Peace Now, only 16 percent of Jerusalem’s Palestinian neighborhoods received building permits from 1991 to 2018, compared to 38 percent of construction permits approved for Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem. The extreme difficulty Palestinians experience in getting construction permits forces many to build without the necessary approvals or live in homes deemed illegal.

Not only do Palestinians face a labyrinth of bureaucratic procedures when building, but a lack of available land as well. Palestinians in East Jerusalem can only build on 17 percent of the land, while 35 percent is labeled as green spaces or conservation areas. In Jabal al-Mukaber, nearly 70 percent of the land is designated as “open space.”

Mohammad Mashal, 71, received his first demolition notice in 1994. He’s paid 200,000 shekels, or $62,000, in fines over nearly three decades. Mashal consistently applied for a permit, but was always rejected. Just last month, he received another demolition order as part of the 62 cases slated for demolition.

Ahmad Akmasri, 25, explained his father built their home before 1967 and decided to extend it in 2006. In 2010, the family started applying for a permit. But, until now, no building rights have been issued.

“We’re talking about 12 years in which we paid up to 100,000 shekels [$31,000] in fees, applications for the engineers, lawyers, all of what you can imagine, and it’s still not yet done,” Akmasri said.

Akmasri’s family is also embroiled in a separate building obstacle due to the Kaminitz Law. Passed by the Israeli parliament in 2017, it allows officials unlimited power in cracking down on unauthorized building, specifically in granting extensions on demolition orders. In addition to the 62 demolition cases in Jabal al-Mukaber, 70 other cases are related to the Kaminitz Law, including Akmasri’s family. With this new legislation, the family faces yet another fine after being unable to secure an extension in 2020 over administrative issues spurred by the coronavirus pandemic.

Raed Bashir, the lawyer representing the neighborhood, submitted repeated objections to the municipal court against the demolition orders—all of which were rejected. But the movement remains steadfast as Bashir plans to submit next month an objection to Israel’s Supreme Court.

Mousa Jumah, 61, received a demolition notice about a decade ago.

“We have no rest in our life,” he said, describing a tense environment not unlike the atmosphere of the March 20 protest. “We are under pressure, and pressure leads to explosion.”

Amid the beating of drums and marching demonstrators inching closer and closer to barricaded city hall doors, Jumah captured the sentiment under the loud chanting: A sense of perpetual uncertainty.

“We have no future,” Jumah said. “We are wasted in this world.”

Jessica Buxbaum is a Jerusalem-based freelance journalist reporting on Palestine and the Israeli occupation. You can follow her on Twitter at @jess_buxbaum.