Source: Foreign Policy in Focus

As the U.S. drone war flares up again in Yemen, a distressingly familiar pattern is playing out.

fter a lull of some two months — a break punctuated by the toppling of Yemen’s government — the U.S. drone campaign in Yemen has resumed.

The pattern that has emerged is distressingly familiar.

While the U.S. government can claim the death of radical preacher Harith al-Nadari, the victims also include Mohammed Tuaiman, a 13-year old boy whose father and brother were killed in a drone strike in 2011.

The new offensive, then, roughly fits the findings of a recent study by the civil rights organization Reprieve, which provided new evidence regarding the civilian death toll of the U.S. drone campaign against suspected militants in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen.

According to Reprieve, a stunning 28 innocent people have been killed for every known terrorist or militant felled by a drone strike. The report echoes recent data of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ), which managed to identify 704 of the 2,904 drone victims who were killed before October 2014 and found that just 10 percent were members of an armed group.

Given this terrible record, it should come as no surprise that the U.S. government frequently describes its drone war in what George Orwell called “political language” — or the jargon that politicians and government officials use to conceal the true nature of their actions. “In our time,” Orwell wrote in his famous 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language,” “political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible.” He observed that “such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.”

The clearest example of political language in the drone campaign is the misleading use of the word “targeted” — for instance in “targeted action” and “targeted strikes,” phrases that President Obama and CIA chief John Brennan have used in reference to drone strikes.

Used in this context, “targeted” wrongfully suggests calculation and precision, and gives the impression that the CIA is going out of its way to make sure that only militants and terrorists are killed. Other examples of distasteful euphemisms include phrases like “engage the enemy” (which means to kill suspected terrorists, whether they have been proven “enemies” or not) and “collateral damage” (which means killing and wounding innocent people and destroying their property).

One particularly offensive term, reserved for internal use in the U.S. armed forces, is “bugsplat.” It refers to the body of a victim after a drone strike, which apparently resembles an insect that has just been squashed.

The use of this kind of terminology constitutes nothing less than a sanitization of military violence. By describing the drone campaign in clinical and — especially in the case of terms like “bugsplat” — dehumanizing terms, the CIA and the Obama administration gloss over the death and destruction that the drone strikes are bringing to Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen. In essence, their “political language” helps them pretend the drone campaign is relatively restrained and painless.

This leads to outright lies like those of Brennan, who claimed in 2011 that there has not been “a single collateral death” from the program, and Senate Intelligence Committee member Dianne Feinstein, who asserted in 2013 that the annual number of civilian casualties has “typically been in the single digits.”

Language, however, is not the only way in which the drone campaign is being sanitized. On the drone operative’s screen, the victim is reduced to a one-dimensional enemy, which undoubtedly makes it easier to pull the trigger. (It is true that some drone pilots develop post-traumatic stress disorders, but the percentages are much lower than those among regular combat units.)

Drone operatives are trained to see the battlefield in black (enemies) and white (non-enemies), and any nuance regarding an individual’s position (is he a dedicated fighter or merely someone who works with the Taliban because he has no other options?) is lost. This reduction of a complex reality to a simple binary scheme is exemplified most tellingly in the so-called signature strikes, drone attacks against unknown individuals who display characteristics and behavioral patterns that mark them out as militants or terrorists in the eyes of the CIA.

Little is known about the criteria that are used to decide whether someone is a target, but the former U.S. ambassador to Pakistan said that all men between 20 and 40 who “associate” with members of armed groups are considered militants.

If true, this means that the drone campaign blatantly ignores the intricacies of having to live in areas controlled by insurgent groups. There are many men between 20 and 40 who interact with the Taliban not because they ardently support the group’s agenda, but because they want to work out a modus vivendi that will allow their communities to live in relative peace. Unfortunately, such subtleties are overlooked in the signature strikes, which fail to take into account the grey area between militancy and peacefulness.

Moreover, viewing the world as entirely made up of targets and non-targets blinds drone pilots to the consequences of their disturbingly cavalier use of military force. When a “target” is “neutralized” or “eliminated,” the mission is accomplished, which means that there is little need to worry about, for instance, the disruption that drones cause in the societies where they are deployed. People in areas where drones attacks are carried out live in constant fear and are sometimes even afraid to leave their houses, one result of which is that it’s become difficult for local leaders to organize meetings regarding the administration of their towns and villages. This undermining of local governance structures, however, is not a consideration in the deeply militarized War on Terror, where achieving the operational goal (in this case, killing suspected militants) is all that matters.

Of course, through investigative journalism and data analysis we have ways of knowing how the drone campaign is being waged and what kind of damage it does, but this does not change the fact that the U.S. government is obscuring reality in ways that make it easier to resort to military violence.

Given the devastating effects of drone strikes — to say nothing of the fact that they fuel resentment against the United States and thus strengthen the support base of armed Islamist groups — this sanitization of military force cannot be left unchallenged. Therefore, opposition to drone strikes should not only address the strikes themselves, but also the ways in which the strikes and their targets are being presented.

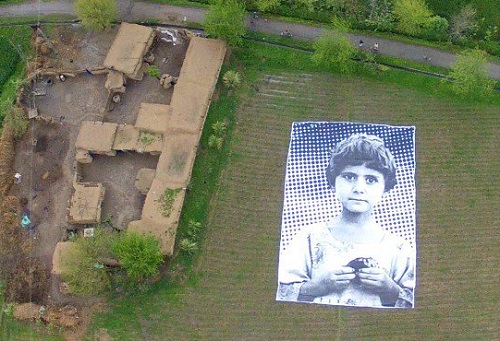

The drone discourse of the U.S. government is the “defense of the indefensible” and should be exposed as such. In doing so, it is crucial to call up the mental images Orwell was writing about, possibly by giving a face to those who got killed. It’s the only way to wage the debate on the drone campaign on the right terms.

Teun van Dongen is an independent national and international security analyst. He holds a PhD degree from Leiden University and wrote a doctoral dissertation about counterterrorism effectiveness. His Twitter account is @teunvandongen.