Clara Ines Yalanda, 36, is a Misak Indigenous woman and a single mother. While she was still a girl, she migrated from an Indigenous reservation to Popayan, the capital of the Cauca region in southern Colombia. With few options available, Yalanda and her family settled in an informal neighborhood.

Twenty years later, Yalanda has been unable to break the cycle of poverty associated with informal neighborhoods. A housing deficit and migration to cities has led rural migrants like Yalanda to construct homes within cities using low-quality materials. These type of homes—which make up 65 percent of housing in Colombian cities—lack basic services, such as a connection to water or a sewage system, and they are constructed outside the bounds of local laws.

Yalanda’s house puts her family’s health and safety at risk because it is near a stream and a sewer drainage system. Currently, only one of Yalanda’s five children lives with her because of her strained finances as well as the poor state of the house.

Early this year, Yalanda’s home and five others’ flooded, with the water having risen more than 1 meter (3.28 feet) high. That forced her to temporarily abandon her home, losing her possessions in the process. Yalanda said the municipality has warned several times that her house is in a risk area—but she added it has not offered a solution.

“They have told me I have to leave,” Yalanda said. “But where can I go? I do not have anywhere else.”

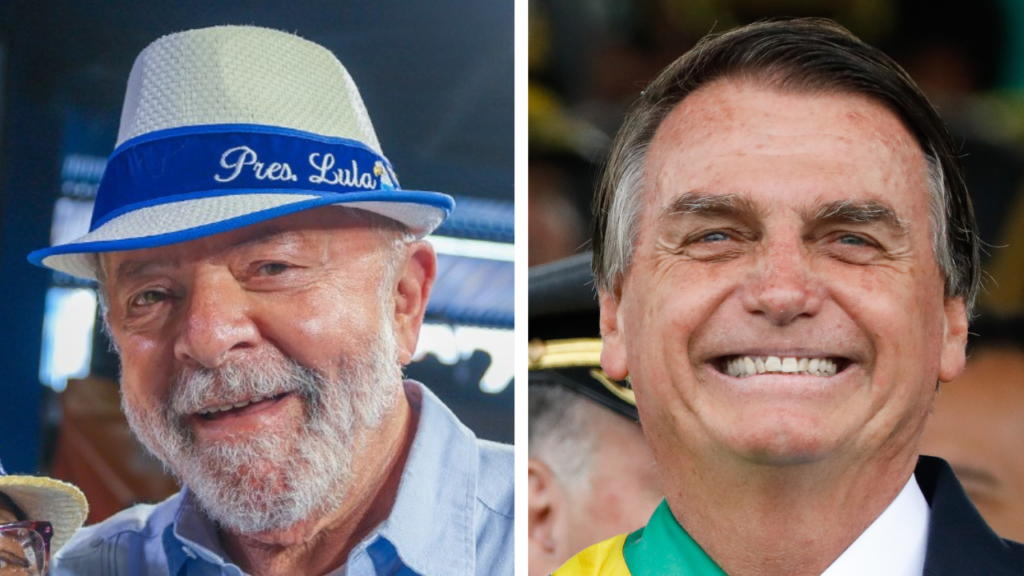

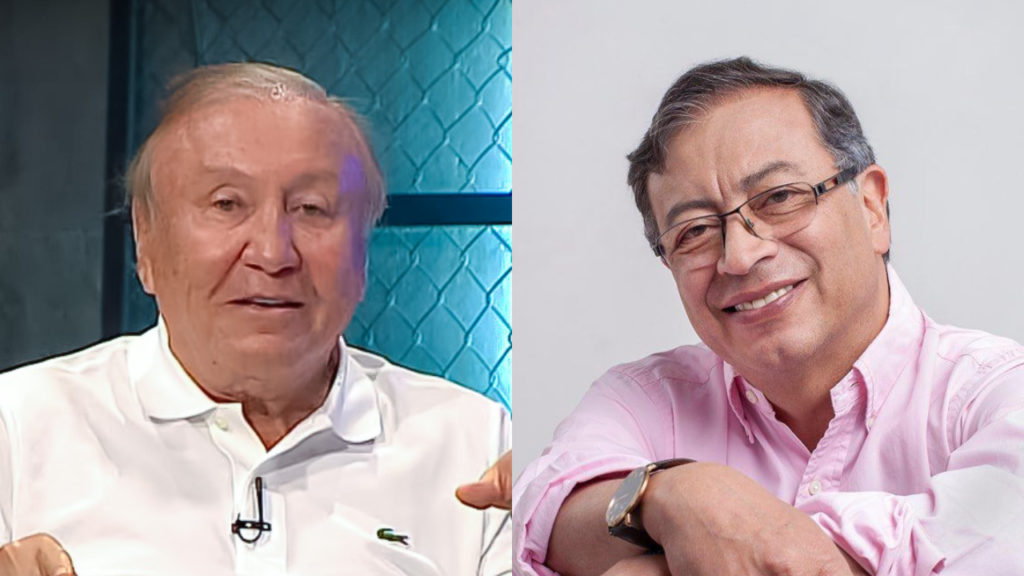

Sunday’s second-round presidential election in Colombia could transform the lives of informal settlement residents like Yalanda. Former-militant-turned-politician Gustavo Petro and millionaire businessman Rodolfo Hernández approach the country’s urban housing crisis and environmental policy in different ways. Meanwhile, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently reported governments must create housing programs that protect the most vulnerable from increasingly volatile weather events global climate change appears to be causing.

Landslides, Fires and Floods Intensify

Precarious conditions like Yalanda’s are not unusual. In Colombia, 65 percent of urban areas are informal, and 20 percent of the population lives in high-risk zones. This increases the exposure of residents to the impacts of climate change, as rainfall and wildfires intensify.

“Informal settlements have been a condition of urban development in Colombia for the last 50 years,” explained Gustavo Carrion, a consultant and on risk management, climate change and territorial planning. “Families migrate to the cities and settle in the most vulnerable areas and [are] the most exposed to landslides, fires and floods.”

According to Colombia’s National Risk Management Unit, La Niña—a weather phenomenon that causes higher-than-normal rainfall—affected between March and June 33,000 families, killed 78 people, injured 91 and caused eight people to remain missing. Although this phenomenon is not a direct consequence of climate change, scientists have warned that La Niña events are intensifying and becoming more frequent due to greenhouse gas emissions.

The Triple Cycle of Vulnerability

Most of the inhabitants of informal neighborhoods had migrated from rural areas that were hit by the decades-long armed conflict and poverty. Much of the conflict revolves around the production and flow of illicit drugs.

Yet, not only are the new homes of rural migrants informal, the way they make their living can be, too.

“I have worked my whole life selling vegetables and depend entirely on this,” Yalanda told Toward Freedom. “I do not have another source of income. The little I earn is for food and some necessities for the children. It is hard.”

Due to these conditions, residents of informal neighborhoods are caught in a triple cycle of vulnerability: First, they lack access to goods and services; second, they suffer material losses during climate-change disasters; and third, they are stigmatized by society and institutions, preventing adequate assistance.

According to Yalanda, the National Risk Management Unit offered a cooking pot and a torch, but denied further support due to their informal condition. A member of the unit reportedly suggested she should go back to her birthplace. Toward Freedom received no response after requesting an interview with the unit.

The IPCC has established “occupants of informal settlements are particularly exposed to climate events, given low-quality housing, limited capacity to adapt, and limited or no risk-reducing infrastructure.”

Early this year, a UN-convened working group of scientists presented the most recent IPCC report. At both the global and regional levels, it is the most comprehensive investigation of how climate change impacts ecosystems, biodiversity and human communities.

The report says “humanitarian responses and local emergency management are vital for disaster risk reduction, yet are compromised in urban contexts, where it is difficult to confirm property ownership.”

‘We Do Not Want Anything for Free’

Rene Delgado, president of the Local Community Action Council, explained residents of El Dorado—where Yalanda lives—have met with government officials many times since they settled in the area more than 20 years ago. A reallocation area was designated, but residents have been unable to participate because of the high loan-interest rates.

“We do not want anything for free,” Delgado said. “The only thing we are asking for is a payment option according to our economic capacities.”

The Cartagena-based Center for Regional Economics found around 70 percent of Colombian households that apply for low-income housing are headed by informal workers. The insecurity associated with this kind of work makes it difficult to apply for a bank loan, necessary for obtaining low-income housing.

“Colombian housing policy focuses on subsidizing loans that drown people financially,” Carrion explained. “Often low-income housing projects do not benefit the most vulnerable families. Instead, it results in a profitable business for a small sector that also participates in policymaking.”

Presidential Candidates on Housing

Previous local mandates set out by each presidential candidate provide a glimpse into what each may offer if elected president.

Petro, the left-wing Pacto Histórico coalition candidate, was mayor of Bogotá between 2012 and 2015. During his term in office, he oversaw the creation of more than 19,000 houses for victims of armed violence and residents of high-risk zones as part of a national housing program known as Vivienda de Interes Prioritario (VIP). Although Petro did not achieve his goal of 70,000 houses, VIPs in Bogota grew by 26 percent. Meanwhile, they shrunk by 27 percent nationwide.

Petro also has highlighted the importance of cities’ adaptability to climate change. Some of his proposals include restoring ecosystems and hydrological systems, reverting to deforestation based on communitarian and public governance of commonly used resources, as well as guaranteeing access to drinking water. The final policy was implemented in Bogotá during his term as mayor.

Hernández—also known as “the engineer”—is running on the League of Anti-Corruption Governors ticket. He became a millionaire by building low-income housing projects in the 1990s. But, by 2019, Hernández failed to deliver on constructing 20,000 low-income houses in Bucaramanga, a promise he made while running in 2015 for mayor of the city. Plus, Hernández’s construction company was involved in a scandal in 2001 for delivering poorly built homes that endangered lives. The company was later liquidated, but it did not compensate the affected residents.

Hernandez provides brief information on his website regarding how he would address climate change. During a presidential election debate on the environment, he expressed he lacks knowledge on the matter. Hernández also has suggested combining the Ministry of Environment with the Ministry of Culture. That has led some to speculate that, if Hernández is elected, the environment would be a minimal concern for his government.

“We are talking about the vulnerability of ecosystems and people,” Carrion said. “For that reason, housing policy has to be articulated environmentally and socially, while also taking into account poverty exacerbated by the pandemic.”

Natalia Torres Garzon graduated with an M.Sc. in Globalization and Development from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, United Kingdom. She is a freelance journalist who focuses on social and political issues in Latin America, especially in connection to Indigenous communities, women and the environment. With photographer Antonio Cascio, she founded the radio-photography program, Radio Rodando. Her work has been published in the section Planeta Futuro from El País, New Internationalist and Earth Island.