Editor’s Note: The following is a first-person account.

I’m a Mayan Calendar keeper without a fixed place to stay, so my Veterans for Peace (VFP) activist friend graciously allows me to stay with him when I have medical appointments in Minneapolis. This past August, he told me about the VFP Golden Rule Project, a year-and-a-half long sailing journey promoting the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. It is going around the “Great Loop”: The Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico, the Saint Lawrence seaway and the Great Lakes.

The story about the renovation and rebirth of the Golden Rule boat that “set sail in 1958 to stop nuclear weapons tests in the Marshall Islands” moved me deeply. I wanted to at least take a picture of such a piece of history and learn more about its noble cause. I was told the Golden Rule would be in Stillwater, Minnesota, which happens to be another place I live from time to time. Unfortunately, I could not find the location of the vessel and I had to travel to the Black Hills for a conference. Upon my return, I learned the boat was no longer in Stillwater. I figured it had left on its journey and I was very disappointed to have missed it.

Later that week, while in the Minneapolis home of my VFP friend, he informed me that the crew of the Golden Rule would be arriving at his house. I could not believe the turn of events! Now I would get to meet the crew and possibly see the vessel.

I got to meet Helen Jaccard, the administrator of the project. We had a long conversation and she asked if I would be part of the crew for the next year and a half. Such an offer shocked me! After some thought, I agreed to be part of the crew for about a month, and that is how my journey began.

Captain Kiko Johnston-Kitazawa, a Hawaiian native and First Mate Stephen Buck are wonderfully understanding and skilled in how to train and sail with inexperienced sailors like me. Dozens of others also have boarded the vessel over the years, as guests, crew or visitors. Currently, we are a crew of four: The captain, first mate, Mary Ann Van Cura from Minneapolis and me.

The Golden Rule is a wood-plank boat built over a sawn frame, which is when wooden pieces are cut together in a shape. It is 33 feet long with a full-length keel that needs 5 feet of water to sail in. It is steered with a tiller, which is a lever attached to the rudder that helps steer the boat. It has 580 square feet of sail with triangular fore and aft sails, while the main sail is a gaff sail. It has four sleeping berths for up to four crew members. Captain Kiko describes sailing in the Golden Rule as “bumpy, wet, cold and fun.”

The boat set sail on September 26. Everywhere we’ve stopped in Minnesota and Wisconsin—Saint Paul, Redwing, Wabasha, LaCrosse—we’ve been welcomed by many supporters.

But nothing compares to what happened in Dubuque, Iowa. The town has over 800 residents native to the Marshall Islands. As soon as we passed Lock and Dam #11 on the Mississippi River, just north of Dubuque, people waved and cheered from nearby docks.

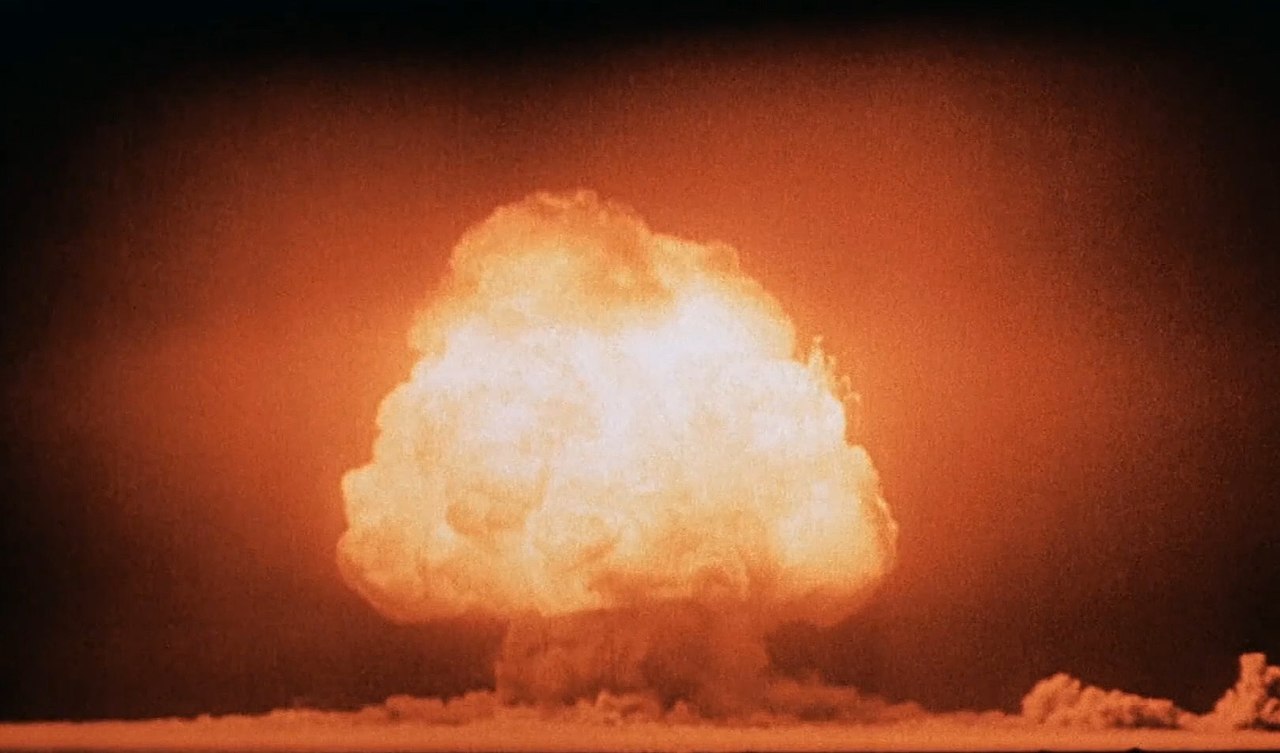

Upon arrival in the Dubuque marina at twilight, we were joined by a crowd of Marshall Islanders and their descendants, who have suffered the consequences of the inhumane deployment of 67 nuclear devices in their homeland. As if losing their home was not enough, Marshall Islanders suffer the nuclear legacy of cancers and birth defects. And now, because of global climate change, catastrophic sea rise is forcing those who remained to emigrate.

Dressed in traditional clothes, the Marshall Islanders sang and played music in honor of the little boat. They also expressed gratitude to the original four crew members who, in 1958, sailed the vessel to stop nuclear testing, risking everything for the good of the planet and the protection of human beings. Undoubtedly, they were also grateful for the new run of the vessel that reminds the whole world of the madness of keeping nuclear arsenals ready to go at any second.

Observing such sincere manifestation, I had to turn my face away. I was crying, feeling this is what a true human being should be doing for all the people and our planet. I was not alone. The crowd was elated. I wish with all my heart every human in the world emulate those four original crew members. Our planet would then be safe from the impending debacle we face. It may happen sooner rather than later, the way we are going.

At a stop in Burlington, Iowa, the mayor presented us with a proclamation welcoming the Golden Rule and calling on residents to meet and learn more about the project.

The journey continues down the Mississippi River. A major problem is the low water level. The boat has been stuck in the muck at least nine times so far. But thanks to the ingenuity of Captain Kiko and First Mate Steve, solutions have been found to continue. Because of these drought conditions, we will not follow the lower Mississippi River but instead will divert to the Ohio, Tennessee and Tombigbee River system.

You can follow the journey of the Golden Rule here. If you’d like to join as crew at any point in the journey you can fill out this application.

Gina Miranda Ajkin is a Mayan calendar keeper aboard the Golden Rule.