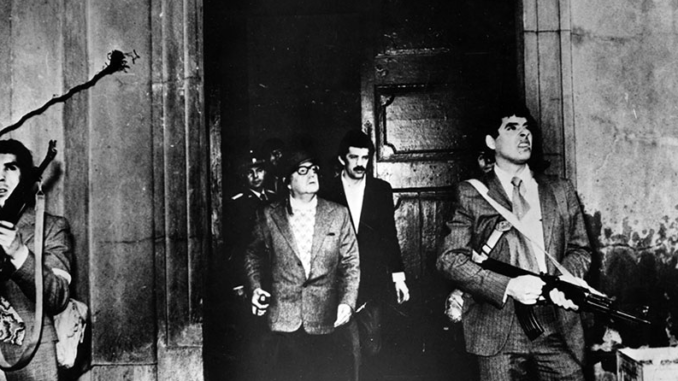

Australian embassy officials in Peru were surprised when they met Dr. Rodrigo Acuña’s revolutionary Chilean parents. They wondered how the both of them had managed to escape the 1973 U.S.-backed coup unharmed. But before approving their refugee application, embassy officials isolated Acuña’s mother, asking her to promise she wouldn’t engage in political activities in Australia. Later, on the flight to Sydney, his father ended up having what Acuña describes as a “post-traumatic stress disorder episode.”

“When he arrived at Sydney International Airport, he had to be placed on a stretcher and given medical attention,” Acuña told Toward Freedom. “That’s how my family arrived in Sydney, Australia.”

Now, Acuña, an academic, is part of a group representing Chilean exiles in Australia. The group has written an open letter to Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne, expressing its dismay at revelations Australia may have collaborated with the United States in the events that led to the removal of democratically-elected Chilean socialist President Salvador Allende.

🙏🏽 @GreenLeftOnline for sharing the letter lawyer Navarro (@Adriana22974030) & I wrote to @MarisePayne @ausgov. It was signed by 70 🇨🇱-🇦🇺 citizens who fled #Pinochet’s regime of State terror which #ASIS & the #CIA helped install. https://t.co/EZcIip9wt8

— Rodrigo Acuña (@rodrigoac7) September 20, 2021

What Documents Reveal

The letter includes several demands, the most controversial being files be fully declassified and details about Australia’s involvement with the CIA and the Pinochet regime be made available to the public.

Declassified documents already reveal the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) were complicit in undermining the government of the sovereign Latin American country in the run-up to the military coup.

Documents prove ASIS installed offices in Santiago, Chile, from 1970 to 1973, with the sole purpose of undermining Allende’s socialist project, leading up to and even after the coup. For example, Australian parliament member E. Gough Whitlam stated in 1977, “… Australian intelligence personnel were still working as proxies and nominees of the CIA in destabilizing the government of Chile.” However, ASIS could not be reached for comment.

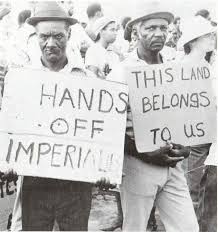

The fall-out that followed the coup was devastating for the normally politically stable country that, until then, had enjoyed a tradition of democracy. Allende was voted into presidency in 1970 with a social-justice agenda that included nationalizing its assets, including its lucrative copper mines, in which U.S. copper conglomerate Anaconda held a huge stake. Chile’s incoming radical agenda threatened the markets and international investors, so the United States began pouring huge sums of money into destabilizing Allende’s Popular Unity administration. Tactics included public relations smear campaigns via CIA-funded right-wing newspaper El Mercurio.

That’s why Acuña said it’s important to denounce Australia’s role in the violent 1973 coup.

“How dare Australia interfere in the internal affairs of a sovereign state in a region as far away as Latin America to please a request from Washington,” he said. “The Allende government was far from perfect, but it was democratically elected by the people of Chile.”

The documents released to Dr. Clinton Fernandes, former intelligence analyst and Australian academic, are just the tip of the iceberg. His repeated requests for further declassification have been denied on grounds the revelations are far too damaging and “must remain secret.” But Chilean coup victims strongly disagree.

“This denunciation of ASIS’ role in the 1973 coup in Chile must be made because we, as first-, second- or even third-generation Chileans, have the right to express it,” Acuña said.

Australia’s Double Talk

Australia is no stranger to taking in Chilean political exiles. The first one was ex-Chilean President General Ramón Freire in 1838. In the aftermath of the 1973 coup, between 100,000 to 500,000 Chileans were expelled from the country or displaced across the globe.

Many sought refuge in the United States and in Europe (Sweden, France, Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom), while around 6,000 were taken in by Australia. The newly arrived refugees experienced severe trauma, because their friends and family members had been disappeared, and the majority had been tortured.

However, alongside refugees, Australia also took in a number of former Chilean secret-service agents responsible for the torture, interrogation and possibly the disappearance of left-wing activists in Chile. For example, Bondi Nannie Adriana Rivas is fighting extradition to Chile, where she will face charges of crimes against humanity. She worked at Cuartel Simón Bolívar, the infamous interrogation center in the capital of Santiago, as secretary to Manuel Contreras, the notorious head of operations for Chile’s secret police, Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA). Rivas is accused of participating in the torture and kidnapping of seven members of the Communist Party, including Victor Diaz, who, like many of Pinochet’s victims, remains missing.

Lawyer Adriana Navarro and Acuña state in the letter that unknown agents harassed many Chilean political exiles in Australia because they supported the return of democracy to Chile. Their political activities included writing letters to local parliament ministers and staging protests in cities like Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Canberra. Acuña said he suspects that like how Australia’s intelligence organizations have a close relationship with the CIA to share intelligence, the ASIS likely also has a close relationship with U.S. allies like Chile.

“That is the only logical explanation as to how someone with such a profile like Rivas even made it into Australia in the first place,” Acuña said. “We Chilean-Australians would not have any dignity or self-respect if we did not denounce in the harshest language Australia’s role in the violent coup in Chile in 1973, demanded an apology and asked for a full declassification of ASIS activities in Chile in the 1970s.”

However, the official state position that revelations may severely harm Australia’s reputation means campaigners may face a lengthy legal battle to uncover the truth.

Carole Concha Bell is an Anglo-Chilean writer and Ph.D. student at King’s College London.