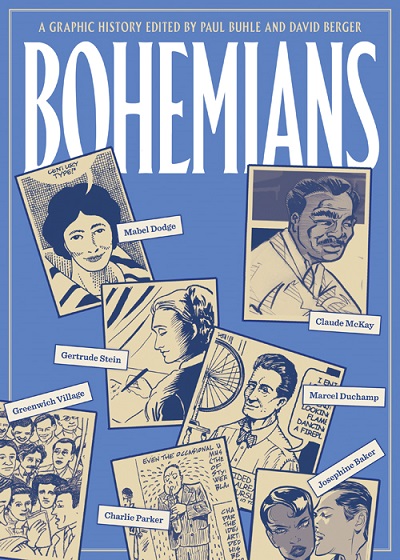

Reviewed: Bohemians: A Graphic History edited by Paul Buhle, et al. Verso, 2014 228 pages, black and white, $16.95

Reviewed: Bohemians: A Graphic History edited by Paul Buhle, et al. Verso, 2014 228 pages, black and white, $16.95

Before there was a counter-culture, there were bohemians. Never confined to a specific ideology, personal style, or mode of expression, bohemians were nevertheless characterized by their artistic temperament, sexual libertinism, and general left-wing outlook.

“Bohemia” was not Bohemia, the region of what is now the Czech Republic. It was not a place, but neither was it no-place, like utopia. It was instead both an outlook and a milieu, something more than a collection of individuals and something less than a community. If one were to write a history of bohemia, it would probably not look much like a history, just as a theory of jazz will not sound like jazz.

So it stands to reason that Bohemians: A Graphic History is only occasionally a history. It is, instead, a series of biographies, the odd moment of cultural studies, a large dose of romantic nostalgia, swatches of poetry, and a sizable collection of comic art. If there is a narrative uniting these disparate elements it is fragmentary and episodic. One catches glimpses of it in the background and feels for it, blindly, just beneath the surface.

The book comprises 28 chapters, plus an introduction, with artists as notable as Peter Kuper, Trina Robbins, and Spain Rodriguez. The art is beautiful throughout, representing a wide range of styles and approaches. Some is rough-seeming, some very polished; some realistic, some extremely cartoonish. A few incorporate photographs or other archival images. The variety reflects the subject of the collection, and may be counted as both a weakness and a strength.

Most chapters center on an individual — Walt Whitman, Victoria Woodhull, Arturo Giovannitti, Henry Miller, Woody Guthrie, Josephine Baker — though others look at a group (German and Jewish immigrants) or an artistic movement (bebop, modern dance), and one recounts the story of a magazine (The Masses). Those that stand out most are those that come closest to straight history. Dan Steffan’s chapter on modern art in New York is one. It quickly but clearly traces the evolutionary course from Stieglitz’s photography to Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism. Another is Sharon Rudahl’s fascinating history of the song “Strange Fruit,” written as a protest by a white, northern, Jewish teacher and made famous by Billie Holiday. The chapter tells of their two very different lives, and the effect that the song had on each of them.

The collection’s main preoccupation is with art, broadly considered — painting, poetry, music, dance, novels — though sex and politics receive nearly as much attention. These elements, being the defining features of a bohemian, constitute the major themes of the book.

Bohemian art, if one may generalize, is transgressive. It may be experimental in technique, politically subversive, obscene by contemporary standards, or may simply originate outside of and rebel against respectable, established canons. Sometimes the art was less controversial than the artist. Bohemian art tended, in any number of ways, to violate entrenched norms governing race, class, and gender. The sense of that artistry is well conveyed here, both by the image on the page and by the discussion in the text. Additionally, and fortunately, much of Lance Tooks’ chapter on Claude McKay is given to reprinting some of McKay’s most powerful and beautiful poetry.

After art, the second theme shaping the figure of the bohemian would be sex. While never pornographic or licentious, Bohemians is certainly not shy about the subject. The authors never pass by an opportunity to tell us who was gay, lesbian, or bisexual, who took many lovers or refused to marry on principle, who posed or performed nude, and who wrote or spoke against the mores of their era. One short chapter — too short, in my opinion — is devoted to free love in a nineteenth-century commune.

The third element of the bohemian character is political. Left puritans and aspiring apparatchiks are often quick to dismiss artists as poseurs and dilettantes. Our stodgy comrades may then be surprised by the political seriousness and personal commitment portrayed in many of these stories. It is not just a question of subject matter — Dada as a protest against the insanity of war, Woody Guthrie singing labor songs — but of real engagement with the political movements of the time. Abel Meeropol did not just happen to choose lynching as a subject for his poetry; he worked with an anti-lynching group, and the first performance of the song, sung by his wife Anne, was at an event organized by the teachers’ union. The poet Giovannitti was a leader in the IWW’s Lawrence textile strike (and imprisoned as a result). Josephine Baker smuggled documents for the Free French during World War II. Clearly there is more to the politics of bohemia than radical chic.

As a volume, Bohemians is uneven, and never quite fits together into a whole. There is no point in reading it straight through, and some chapters may be skipped altogether. But the parts that are strong are very strong — interesting, evocative, beautiful, and often surprising. Approach this book as you would a good party: talk to everyone a little, stay with the conversation for just as long as it holds your interest, and try to have some fun.

Kristian Williams is the author of Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America, and an editor of Life During Wartime: Resisting Counterinsurgency. He is presently at work on a book about Oscar Wilde and anarchism.