Correction: The definition of Haitians of Dominican descent has been clarified. The length of the constructed portion of the border fence has been corrected. The name that Dominican officials had given for a victim has been updated, based on newly obtained information.

Whenever Malena goes to work or heads out to study, she tries to leave her home very early and return after dark. The 33-year-old mother of five does so for fear of being detained by the Dominican Republic’s immigration agents, even though she is Dominican.

Born and raised in a batey, a settlement around a sugar mill in the San Pedro de Macorís province, Malena is the daughter of Haitian sugar cane workers who arrived in the Dominican Republic in the 1970s, during the U.S.-backed Dominican dictatorship of Joaquin Balaguer.

Malena now lives in La Romana, also in the eastern part of the country. She has three sisters, two of whom have an identification card, acquired through a regularization plan for foreigners. Meanwhile, she and her other sister don’t have any documents. Close encounters with immigration authorities are normal.

“On a trip to the capital, Migration [officers] stopped the bus,” Malena recounted. “They said to a young man: ‘Papers, moreno!’ And since he only had a Haitian ID card, they took him off the bus. They only look for Black people. Luckily, they didn’t look at me. Sometimes by WhatsApp, I’m warned not to pass through some place because Migration is there. It’s always a danger.”

Malena and her sisters are some of the more than 200,000 people affected in the last 10 years by Constitutional Court ruling 168-13, according to estimates of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. This ruling deprived Dominicans of Haitian descent who had been born after 1929 of their citizenship. As such, the impacts of statelessness are rampant.

“My children have no papers,” Malena said. “Without papers, you can’t have health insurance. You can’t have a good job. I had to repeat 8th grade because I couldn’t take the national test. The same thing happened to my son.”

Mass Deportations

Since 2021, the government of Luis Abinader has been promoting a campaign of mass deportations of the Haitian immigrant community. This also affects Dominicans of Haitian descent. Those are people who were born in the Dominican Republic, have Haitian parents or grandparents, and often are stateless, as in Malena’s case. The head of the General Directorate of Migration, Venancio Alcántara, declared recently that between August and April, more than 200,000 Haitians had been deported. “A record in the history of this institution.”

This statistic shows its true dimensions when contrasted with the size of the Haitian migrant community and the population of Dominicans of Haitian descent. Although no recent official figures exist, Dominican Ambassador to Spain Juan Bolívar wrote an opinion piece in June that estimated both populations, when counted together, at less than 900,000 people, or about 8 percent of the country’s population of 10.6 million. Bolívar’s estimation is based on the 2017 National Immigrant Survey, conducted by the National Statistics Office.

That means 22 percent of Haitians had been deported between August and April.

This is why Dominican and Haitian organizations have warned of the danger that the mass deportation campaign could turn into a process of open ethnic cleansing and consolidate an apartheid regime, as previously reported in Toward Freedom.

Extortions, Theft and Violence at the Border

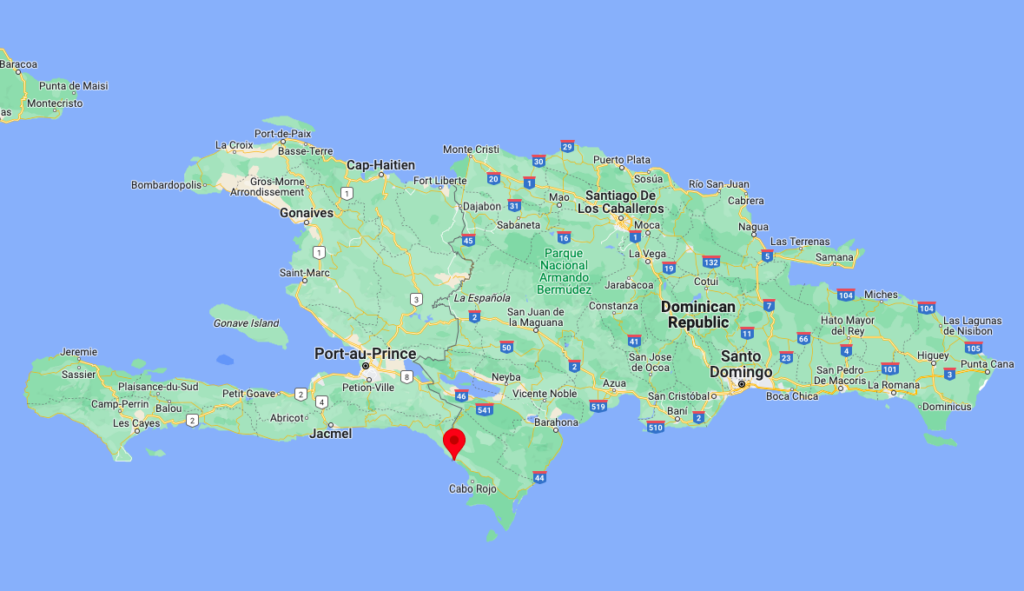

One of the flagship projects of the Dominican government is the expansion of a border fence. Previous governments built the first 23 kilometers (14 miles). Now, fence construction is continuing, so it can cover 164 kilometers (101 miles). The Abinader government insists in forums, such as the United Nations, on the need for the “international community” to militarily occupy and “pacify” Haiti, complaining about the “burden” the neighboring country represents for the Dominican Republic.

However, the violence of the Dominican state has crossed the border into Haiti.

On March 19, members of the Dominican military attacked the Haitian border village of Tilory in the north, killing two people—Guerrier Kiki and Joseph Irano—and wounding others in their attempt to suppress a protest. According to a statement signed by Dominican and Haitian organizations, the Dominican military regularly engages in extortion and theft, including the seizure of motorcycles and other property, which led to the protest.

This is not the only recent cross-border incident. On August 5, an agent of the Dominican Directorate General of Customs (DGA) shot and killed 23-year-old Haitian, Irmmcher Cherenfant, at the border crossing between Pedernales and Anse-A-Pitres, in the southern end of the north-to-south Dominican-Haitian border. Dominican officials identified Cherenfant as Georges Clairinoir. The DGA and the Dominican Ministry of Defense justified Cherenfant’s killing as an instance of self-defense. Dominican social organizations questioned this version, pointing out contradictions in the official communiqués.

A human rights defender from Anse-A-Pitres who spoke with witnesses said the conflict began when the victim refused to pay a customs guard to be allowed to transport a power generator purchased in the Dominican Republic. After Cherenfant was killed, a struggle ensued, in which the guard was disarmed by Haitians. Subsequently, the Dominican military fired weapons of war indiscriminately into Haitian territory, injuring two people. The human rights defender, who works for a local organization, asked not to be identified for security reasons.

The Dominican government paid a compensation of 400,000 pesos (approximately $7,200) to Cherenfant’s wife the following week. But when the community mobilized on August 12 against military violence and in memory of the victim, the Dominican military threatened some of the protest organizers that they would be prohibited from entering Dominican territory.

‘A Vibrant Democracy’

U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman visited Santo Domingo on April 12 and met with Abinader. According to State Department spokesperson Vedant Patel, they discussed their “deep ties” and “shared democratic values,” as well as regional security issues, including the “urgent situation in Haiti.”

During her visit, Sherman recorded a video message in the colonial zone of Santo Domingo, extolling the country as a tourist attraction and calling the political regime a “vibrant and energetic democracy… a strong and exceptional partner with the United States of America.”

In her tour of the colonial zone, Sherman can be seen escorted by the mayor of the National District, Carolina Mejia, a member of the ruling Modern Revolutionary Party (PRM), and by Kin Sánchez, a guide of the Tourism Cluster. Significantly, Sánchez was part of a mob led by the neo-fascist organization, Antigua Orden Dominicana, which attacked and shouted racist slogans against a cultural activity held on October 12 that was intended to commemorate Indigenous resistance. The complicity of the National Police caused nationwide repercussions.

After Sherman’s visit, Republican U.S. Congressmember Maria Elvira Salazar and Democratic U.S. Congressmember Adriano Espaillat, announced the U.S. State Department would withdraw a November 19 travel alert warning Black tourists of racial profiling by Dominican immigration authorities. The April 17 travel advisory only mentions risks related to criminality. Dominican Tourism Minister David Collado welcomed the move as a “very positive and appropriate” measure, describing the U.S. as a “strategic partner.”

Meanwhile, two days after Sherman’s visit, Haitian driver Louis Charleson was shot and killed by a military officer in the Dominican border town of Jimaní following a traffic altercation. A young Haitian man was wounded, too. The Haitian Support Group for Returnees and Refugees (GARR) denounced the impunity that covers the Dominican military and police in the border area. The agent who murdered Irmmcher Cherenfant last year in Pedernales continues to hold the same position at the Directorate General of Customs. He has not been dismissed or prosecuted.

“As always, Dominican officials present the simplistic argument of self-defense to comfort the offending soldiers with impunity,” GARR stated.

Vladimir Fuentes is the pen name of a freelance journalist based in the Dominican Republic.