This article originally appeared in People’s Dispatch.

A panel of environmental and human rights activists acted as judges in a People’s Health Tribunal organized by African communities impacted by the operations of extractive corporations Shell and Total Energy. Supported by organizations like Medact, We the People, the People’s Health Movement, #STOPEACOP, and others, they found the corporations guilty of harming the health of people across Africa. Nnimmo Bassey, Jacqueline Patterson, Kanahaus Manuel, and Dimah Mahmoud condemned Shell and Total’s activities, stating that they were “extremely harmful to the livelihoods, health, right to shelter, quality of life, right to live in dignity, quality of environment, right to live free of discrimination and oppression, right to clean water, and right to self-determination.”

This edition of the People’s Health Tribunal was built as activists witnessed extensive greenwashing by the oil and gas industry at COP 27 in Egypt last year. In response, they became even more determined to support the struggles of communities in Africa who are affected by the corporations who attempted to gaslight the public at COP 27.

However, governments in the Global North, where most extractive corporations have their headquarters, still choose to ignore the destruction caused by these industries. In 2022, Shell made a profit of $40 billion, while Total Energy ended the year with US$36 billion in profits. These profits came at the expense of the health and lives of people living in regions where these corporations operate.

Uprooting Set the Ground for Total’s LNG Operations in Mozambique

Decades of exploitation of African land have resulted in devastating consequences, including air pollution, water contamination, deforestation, violence, land grabbing, and forced migration. People in the Niger Delta and Mozambique experience these things daily. Omar Elmawi, who provided an overview of Total’s impact on Mozambique communities, emphasized that in the current situation, “everyone loses, except Total.” Elmawi said he believed that African countries must take control of their own resources and development to make sure that justice is restored.

In Mozambique, Total Energy’s plan to construct an onshore liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility led to the displacement of hundreds of families dependent on farming. Total’s plans also decimated traditional fishing activities, leaving people destitute. Instead of providing the uprooted communities with adequate living conditions and compensation, the company’s plan resulted in people being left without shelter, living in refugee camps, and exposed to violence.

At the same time, pointed out Elmawi, the company was not shying away from tax evasion, bleeding even more resources out of the country and leaving Mozambique without necessary means to build essential infrastructure.

Similar experiences were echoed by activists from Uganda and South Africa, who bore witness to the baleful behavior of Total Energy and Shell in the face of the communities which they so violently entered. The testimonies also highlighted the environmental impacts being shouldered by the same communities, as floods and storms regularly devastate local food production.

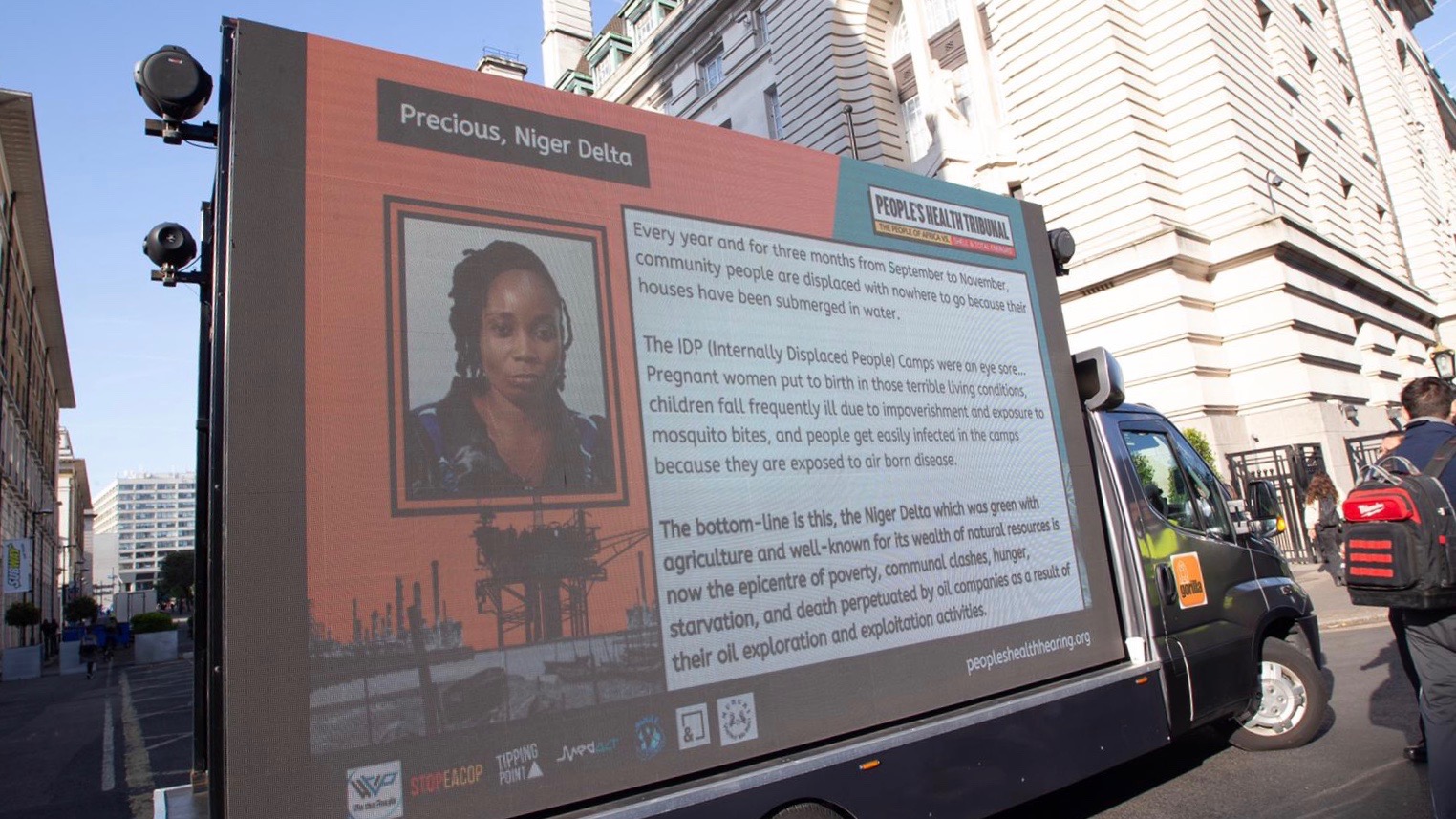

Shell Operations in the Niger Delta

Shell has been furiously extracting resources in the Niger Delta for over 60 years, attracting more companies to exploit the region due to its rich reserves. Videos from villages in the Niger Delta clearly show oil contamination of water sources, while Shell ignores the grievances raised by the communities. With Shell’s arrival, people’s health deteriorated, in addition to the environmental devastation caused by oil and gas extraction. People began suffering from previously uncommon diseases, including blindness, respiratory problems, and kidney disease, according to one of the testimony-givers.

However, the people of the Niger Delta aren’t asking for charity or pity; they are determined to fight for justice and see Shell restore the land it has devastated. In the light of that, Shell’s announcement of divesting from operations in the Niger Delta is seen as inadequate by community members. They view it as an attempt to evade responsibility for the damage caused over the years. After all, they pointed out, Shell would not be giving up on their business—they would be simply selling their assets to someone else.

The judges stressed the need to establish infrastructure for a reparative justice process to achieve true reparation for affected communities. They also called for Shell and Total Energy to halt all plans for expanding existing fossil fuel extraction sites, implement a permanent moratorium on exploring new sites, and cease supporting violence against communities through military, paramilitary groups, or private security forces.

In order to achieve that, it is necessary to constantly bear witness about the destruction caused by extractive corporations. By doing that, the people who spoke about their experiences during the People’s Health Tribunal showed extreme courage and deserved respect, said Nnimmo Bassey. “Staying alive and speaking out is the best we can do,” he said.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch. For more articles and to subscribe to People’s Health Dispatch, click here.