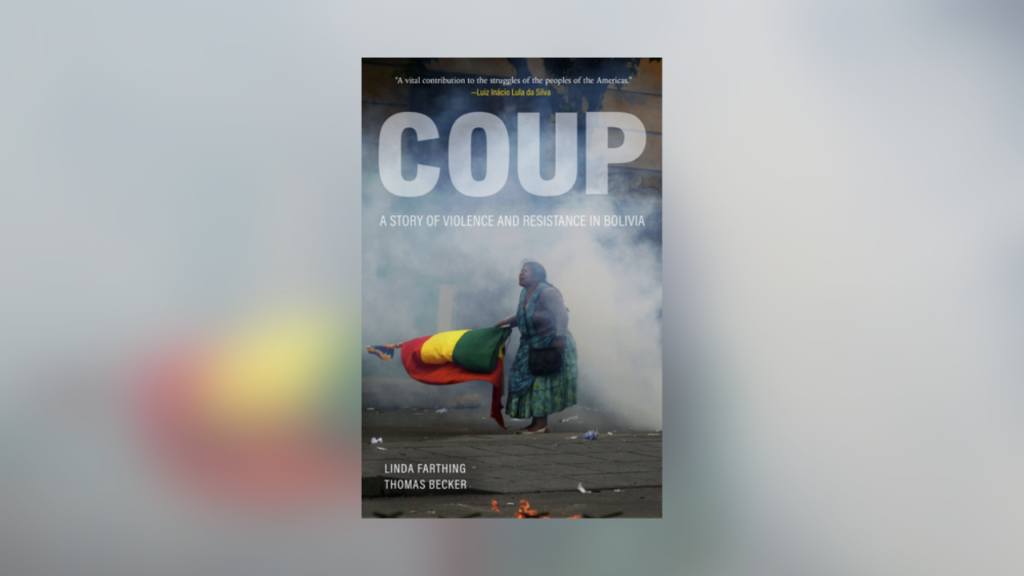

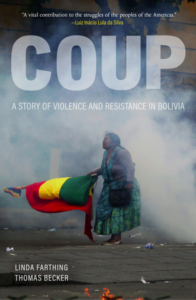

Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia, by Linda Farthing and Thomas Becker (Haymarket Books: Chicago, 2021)

A new book, Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia, provides an in-depth, balanced view of the 2019 coup and the ongoing Bolivian revolutionary process. Journalist Linda Farthing and attorney Thomas Becker’s 306-page book evaluates the balance of class forces that led to the coup, as well as the anti-imperialist forces who were ultimately able to repel it and seize political power again in the plurinational state of 11.4 million.

The Plurinational State of Bolivia Emerges

In 2006, Bolivia embarked upon a new path, with an emphasis on social benefits reminiscent of revolutions past, from the Soviet Union to Nicaragua to Grenada.

The plurinational leadership, representing 36 different Indigenous languages, fought against a legacy of white supremacy, which many experienced as “apartheid without pass laws” (30). (Pass laws were used in South Africa to police Africans, forcing them to carry identification at all times.) In Bolivia, they established the Ministry of Institutional Transparency and Fight Against Corruption to uproot corrupt interests and clientelism sabotaging government attempts at reform (33). Social movements were now part of the people’s government. Part II of the book, titled “Fourteen Years of the MAS,” charts these enormous social gains that made it clear to the world that the decolonization of every facet of society, from the educational system to the media, was possible (71). MAS stands for Movimiento al Socialismo, or Movement Toward Socialism.

At the helm of this long overdue social transformation was coca farmer, trade unionist and veteran of the Cochabamba Water War and Gas Conflict, Juan Evo Morales Ayma. Morales emerged as the inspiring local and international representative of the Aymara, Quechua, Uru, and other Indigenous nationalities and working-class mestizos long marginalized in Bolivian politics and the economy. Every September at the United Nations General Assembly, Morales—as Bolivia’s president—articulated a defense of Pachamama, the Andean Earth Mother, spearheading a trailblazing, international environmental movement from the bottom. At the same time, MAS leadership, particularly Morales, was present in Managua, Havana and Caracas, forging an internationalist, Bolivarian unity project.

It was clear to all anti-imperialist observers that Bolivia and the global hegemon to the north—the United States—were on a collision course. In 2008, MAS leadership ordered U.S. ambassador Philip Goldberg to leave the country after they found out USAID had used its Office of Transition Initiatives to give $4.5 million to the pro-secessionist Santa Cruz departmental government. The Bolivians then expelled the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency from their country.

Supporters of profound social change inside and outside of Bolivia wondered: How long before imperialism and their local agents seek to decapitate this vital leadership and halt the progressive social changes under way?

‘Black November’

Like all U.S.-backed coups in South America and the world over, this one was based on violence and intimidation.

Farthing and Becker document the mobilization of fascist groupings based out of the European enclave of Santa Cruz, as well as police raids targeting MAS leaders and the destruction of the wiphala and other Indigenous symbols. Lighter-skinned European descendants and mestizos screamed “F*ck Pachamama,” blamed the MAS for the corruption that existed in the country, and forced Morales and other leaders to go into hiding and exile (141).

Once in office, Añez and her cabinet picks worked to undo 13 years of social gains. They retired their embassies from progressive countries, kicked out 725 Cuban doctors, and re-established relations with the United States and Israel (166).

In November 2019, 35 people were murdered for standing up to the coup (155).

The class-conscious researchers dedicate chapter 5 to documenting the extreme, racist repression to which millions of Bolivians were subjected. Through interviews with massacre survivors, the authors reconstruct how soldiers shot into crowds that had marched outside of the city of Cochabamba, turning another city called Sacaba into a “war zone” (147). “At the end of the day, Añez’s fourth in office, state forces had killed at least 10 and injured over 120 protesters and bystanders. All casualties were Indigenous, not a single police officer or soldier was harmed” (149).

When Lucho Arce took power as president in 2021, he recognized the blood that was shed to restore MAS to power, “asking for a moment of silence for those killed in Senkata, El Alto; Sacaba, Cochabamba; Montero, Santo Cruz, Betanzo, Potosi, Zona Sur La Paz; Pedregal, La Paz” (194).

Resuming the Path of Revolution

On November 9, Morales returned to his homeland. Millions came out into the streets, converging on Chapare, a MAS base, to see their humble leader, who never stopped standing up to the U.S. empire and their local agents. Admiring families brought him his favorite meal, chuño (freeze-dried potatoes) and charque (dehydrated meat), expressing how Morales “has made us proud to be Indigenous” and “we wouldn’t be here without Evo” (203).

Arce was the economic minister under Morales. He represents the ongoing defense and promotion of the class interests of the poor. Arce’s government presented this month an economic reconstruction program dedicated to building additional housing projects for the underprivileged, infusing $2.6 billion into the economy to satisfy mass consumer demands, opening up lines of credit, placing taxes on personal fortunes above $4.3 million, and increasing subsidies and pension plans (200).

Farthing and Becker present a balanced view of the Bolivian experience anti-imperialists everywhere can learn from. They don’t hesitate to dive into MAS’s challenges, excesses and mistakes. They contextualize the errors within centuries of Spanish colonial bureaucracy and underdevelopment. Potosi historian Camilo Katari also examines this wicked inheritance and how it continues to plague the Bolivian state today. Revolutions, now in the driver’s seat of history, don’t just attract the best of us. Careerists, opportunists, and other neocolonial bitter-enders jostle within local and national bureaucracies to secure their own sinecures and petty interests.

The Bolivarian Camp Pushes Forward

Bolivia occupies a unique space in the U.S. left’s imagination. Sometimes it may seem like they are spared some of the harshest neoliberal critiques. The truth is CNN en español and other corporate outlets continue to function as mouthpieces for the Añez camp and vilify Bolivia’s process. The full slate of corporate media outlets and leftist-liberal outlets go after MAS arguably as hard as they go after Nicaragua, Venezuela and Cuba.

Bolivia, Nicaragua, Cuba and Venezuela—the anchors of the Bolivarian camp—have been spearheading the multi-centered global process. Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro recently finished high-level meetings with Nicaraguan and South African leadership to continue building unity against the United States’ hegemony. These maroon states—those in which a large percentage of the population is of African descent—represent a permanent threat to the unipolarity U.S. transnationals are hellbent on imposing around the globe.

Coup is an important contribution, lest we forget where we need to stand and fight at this historical moment as neoliberalism and unipolarity are on the wane and a multipolar world surges forward from below.

Danny Shaw is a professor of Caribbean and Latin American Studies at the City University of New York. He frequently travels within the Americas region. A Senior Research Fellow at the Center on Hemispheric Affairs, Danny is fluent in Haitian Kreyol, Spanish, Portuguese and Cape Verdean Kriolu.