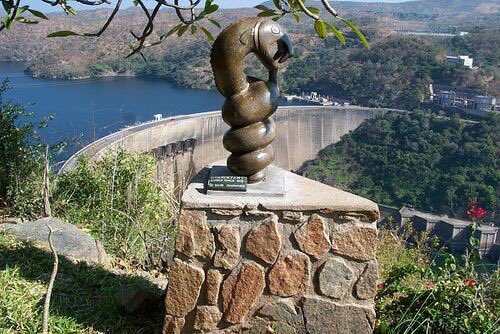

People have lived on both the Zimbabwean and Zambian sides of the Zambezi River of southern Africa for centuries. Their lives revolved around the river. They say their god, the nyami nyami, lives in its waters.

The Zambezi is Africa’s fourth-longest river, flowing from northwestern Zambia into Angola and Botswana, then forming the Zimbabwe-Zambia border, before it empties into the Indian Ocean off Mozambique to the east. For centuries, the people fished in this river, fetched drinking water from it and harvested crops twice a year on its fertile floodplains. As a result, they call themselves basilwizi, which, in their Tonga language, means the “people of the great river.”

Now, they are only basilwizi in name, with no water to drink or with which to grow crops. They need a government permit to fish on Lake Kariba or on the river further upstream.

“We are just here, thirsty,” BaTonga Chief Saba told Toward Freedom, as he stood in Binga District, Matabeleland North Province located in western Zimbabwe, some 800 km (497 miles) from the capital city of Harare. “Some of us drill boreholes, but even if they drill up to 100 meters (109 yards), they frequently hit dry holes. Where they are lucky to get [water], it will be salty due to the abundance of coal in this area. Come the dry season, the boreholes dry up. Even the hot springs we have yield salty water, as well.”

One of 17 BaTonga chiefs in the Binga District, Chief Saba’s parents were among the approximately 23,000 BaTonga villagers displaced from the southern bank of the Zambezi between 1957 and 1962. That made way for the construction of Lake Kariba, the world’s biggest dam constructed by humans. In Zambia, 34,000 people of the BaTonga tribe were removed, too. The 23,000 BaTonga people were scattered in four arid districts in Zimbabwe: Binga, Gokwe North, Hwange and Nyami Nyami. Their population has grown to about 300,000, while displaced in Zambia number 1.3 million.

‘Fish Is Our Gold’

The dam generates electricity that lights up the country. It is home to tourism facilities, as well as to the annual tiger-fishing contest that attracts tourists from southern Africa and beyond. However, the evictees are ranked among the country’s poorest, and trace their poverty to their removal from the fertile shores of the river and to their resettlement in arid places.

“We are people of the great river, so we demand access to it,” Chief Saba said. “Fish is our gold, so we want our people to have special clearance to fish on the lake as their fathers, grandfathers and ancestors used to do.”

Saba added his people want the government and its development partners to build irrigation to help alleviate poverty.

The Zimbabwe Peace Project, a local non-governmental organization (NGO), citing the 2017 Poverty Report by the Zimbabwe Statistical Agency, said Binga was the second highest impoverished district at between 38.4 percent and 51.2 percent. About 50.1 percent of households were classified as “extremely poor.” Food insecurity, as well as lack of access to health, educational and transport services, are rife.

The government is building a $48 million, 42-kilometer (26-mile) pipeline from Deka on the Zambezi River to transport water to cool a 1,500-megawatt, coal-fired power plant at Hwange.

“The pipeline is too far from us,” Chief Saba said. “If we were closer, perhaps we stood a chance of getting some water at communal water points that authorities always set up along such pieces of infrastructure to enable communities to benefit from exploitation of local resources. Because we don’t have reliable water sources, the only alternative is the Zambezi.”

Natural Resources Under Foot

Binga is situated in a coal-rich area. The southern African nation’s biggest coal mine, Hwange Colliery Company Limited, and about a dozen smaller ones, populate Hwange District, Binga’s southwestern neighbor.

The district is blessed with a number of natural resources, such as coal, diamond, gold, lithium, tantalite, timber, wildlife and the Zambezi River. However, the only resources being extracted are coal, timber, wildlife and fish.

In terms of fishing however, a Zimbabwean named Prince Mathe argued in a September 2021 paper, “Vulnerability and Contribution of Fisheries as a Livelihood Strategy in Kani ward, Binga, Zimbabwe,” that the cost of permits limits the BaTonga people’s access to the river and the lake.

“…If one is found fishing illegally, he or she pays a fine worth [sic] $1,500 … failure to do that, they face prosecution.”

The Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority has fixed the fishing permit for people using commercial motorized boats at $1,000 yearly and $300 for those using canoes.

‘Treated Like Animals’

About 57 percent of the land that now sits at the bottom of the lake was arable and owned by the BaTonga, says a Zimbabwean NGO that champions BaTonga rights, Basilwizi Trust, quoting a World Commission on Dams report on Lake Kariba. The document adds that the BaTonga were “‘treated like animals or things rounded up and packed in lorries’ to be moved to their new destination … The racist attitude of the time did not consider the resettlement of Africans as a problem.”

Basilwizi Trust adds:

“The dam’s poor record of resettlement left a huge black mark on the project, which has never been adequately addressed by the parties responsible for building the dam. The colonial and post-independence governments and the major funders and beneficiaries of the dam continue to neglect the relocated people on the Zimbabwean side of the reservoir.”

The trust has demanded reparations in the form of sustainable development programs/projects for the BaTonga and Korekore people in Nyami Nyami District. (While nyami nyami is the name of the BaTonga people’s god, a Zimbabwean district where other BaTonga were forced to move to is called Nyami Nyami. In that district, the BaTonga are called the Korekore people, while in Binga district they are called BaTonga.) The Zambian government compensated each displaced person with $270, but the BaTonga of Zimbabwe were not paid.

A recent paper, “Local knowledge and practices among Tonga people in Zambia and Zimbabwe: A review,” states that prior to the construction of Lake Kariba, the community mainly practiced flood retreat cultivation in their incelela, small plots of land along the riverbank. The mineral-rich soils combined with their system allowed the population to cover their basic needs and harvest twice a year. Now, poverty is widespread among the people.

“Although the dam was built to provide electricity in Zambia and Zimbabwe, up to today, Tonga people have scarce access to electricity,” it adds.

Bringing Water to the People

At Dopota Village in Chief Nelukoba’s area in Hwange District, the grievances are the same as those in Binga.

“We have a solar powered borehole in the village, but it is often without water,” Evans Shoko, head of Dopota Village, told Toward Freedom. “We rely on another one that was drilled in 1968 to serve Dopota Primary School, but it is also unreliable due to the general dryness in the area.”

One garden serves 22 out of 36 households in the village. The garden provides just enough vegetables to prepare relish and small parcels to sell to raise just enough money for isigayo. In the local Ndebele language, isigayo is the payment for milling maize, the country’s staple food.

“It is not transformative at all,” Shoko said, “so what the people want is water from the Zambezi for drinking and to support irrigation schemes.”

Shoko’s village is about 5 km (3.1 miles) away from the Deka-Hwange pipeline, so he hoped authorities would set up a point from which villagers could draw water.

The village is less than 6 miles from Hwange National Park. Shoko said animals, especially elephants, stray out of the park to look for food and water in the village, resulting in damaged crops.

“Sometimes they end up killing people.”

Matabeleland North Provincial Minister Richard Moyo said the government is aware of the challenges the BaTonga face.

“We are drilling boreholes in the district and pushing ahead with the Bulawayo Kraal Irrigation Scheme, which will see up to 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) being put under irrigation,” he told Toward Freedom. The Bulawayo Kraal is about 10 km (6.2 miles) south of the Zambezi River in Binga District.

Moyo said, as of October, the province had drilled about three boreholes out of 17, which are earmarked for chiefs’ homesteads. Last year, President Emmerson Mnangagwa allocated a fishing rig to each of the district’s 17 chiefs, Moyo added. Through this program, the people are able to fish, obtain relish and sell surpluses. Plus, jobs operating the rigs have been created. Moyo said some people in the district would benefit from the Gwayi-Shangani Dam project because of nutritional gardens and irrigation schemes.

“But the issue is not just about water,” Moyo said. “We are building roads, the Binga airstrip is now operational after the government rehabilitated it, so tourism is picking up. Binga Polytechnic [College] enrolled its first intake [of students] last year… So, yes, there are challenges, but we are not leaving Binga behind.”

Thulani Mpofu is a Zimbabwean freelance journalist based in Harare, the capital. He has an interest in development issues. Some of his work has appeared in Canada-headquartered Natural Gas World, Thailand-based Tobacco Asia and South Africa’s Farmers Weekly.