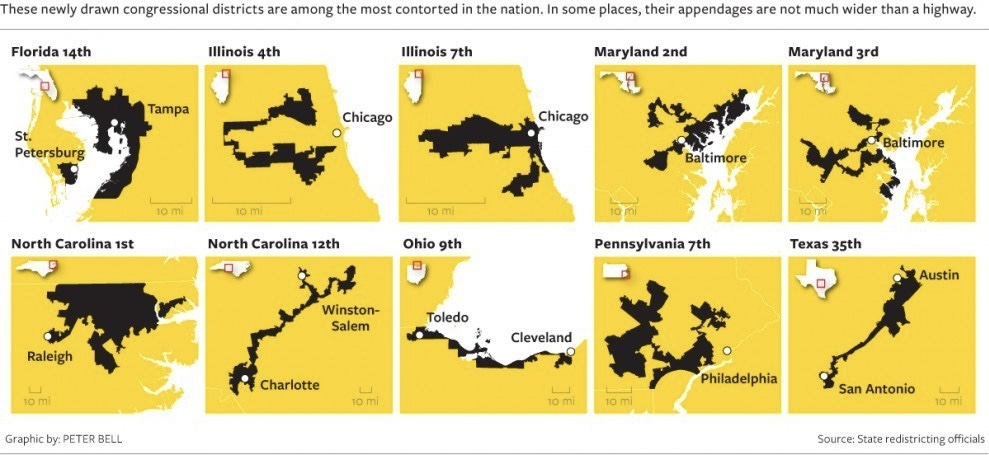

Political maps are “gerrymandered” if they increase one party’s advantage or provide “incumbent protection.” And the boundary lines look strange.

Greg Guma (https://substack.com/@mavmedia)

Most people know that more than 50 Texas Democratic lawmakers recently relocated — some say “fled” — to Illinois to prevent the Texas legislature from achieving quorum and passing laws. It was also hard to avoid hearing about Governor Greg Abbott’s response to that — threats to call “special session after special session after special session” on a redistricting bill.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, a MAGA Republican who will challenge US Sen. John Cornyn in next year’s midterm elections, filed a lawsuit to order the return of the Democrats. Not to be outdone, Cornyn asked the FBI to investigate and find them.

The interstate showdown turned into a temporary truce on August 18, however, when the Democrats returned to their home state and claimed victory after a 30-minute House meeting ended without a vote on the redistricting bill. According to Gene Wu, chair of the Texas House Democratic Caucus, “We killed the corrupt special session, withstood unprecedented surveillance and intimidation, and rallied Democrats nationwide to join this existential fight for fair representation — reshaping the entire 2026 landscape.” On the other hand, Gov. Abbott has already called another session.

Some people may even know that the GOP redistricting plan was ordered up by President Trump, who thinks he “deserves” at least five additional Congressional seats, and that the Texas Democrats, who had sheltered in the Chicago area with the support of local churches and activists, think the whole scheme is unfair.

But for most people, that’s about as far as it goes? Few people know much about redistricting. Even fewer can tell a gerrymander from a salamander, although the two are connected in the history of the obscure political tactic that could determine whether voters in America continue to pick their representatives, or the reverse — elected officials picking their voters — becomes standard practice.

Let’s begin with redistricting, the process by which the boundaries of electoral districts for Congress and state legislatures are determined in each state. Every 10 years the US Census kicks off the process of reapportioning seats in the US House of Representatives by reporting out population changes. Each state then redraws the boundaries of its congressional districts, attempting to include roughly equal numbers of constituents in each one. It’s briefly outlined in Article 1, Section 4 of the Constitution.

In the past, the Supreme Court has ruled that it is mainly the responsibility of states. Normally, the years immediately following each Census are the time to do it. But sometimes states are forced to redistrict based on court cases if their maps violate the Constitution or other laws. Less often states choose to redistrict “mid-decade,” if their laws or state constitution permit that. Texas redistricted in 2003, for instance, even after the legislature enacted a map following the 2000 census — and after that map was replaced by a different court-ordered map.

The process sparks frequent debates and often becomes a political football. Both major parties accuse their opponents of exploiting the line-drawing process to help themselves and disadvantage the other side. That’s where gerrymandering comes in, a strange word used to describe the strategic drawing of district boundaries to increase the chances of future electoral success for one party or another.

Originally hyphenated as “Gerry-mander,” the term was first used in 1812, in the Boston Gazette, in reaction to the redrawing of Massachusetts’ state senate election districts under Gov. Elbridge Gerry. Although he found the proposal “highly disagreeable,” he signed the bill, and his name became connected with the controversial process. Although his party — the Republican-Democrats — held onto control of the legislature, one of the remapped districts in the Boston area was said to resemble the shape of a mythological salamander. It was lampooned in cartoons as a strange winged dragon, clutching at the region.

These days political maps are considered “gerrymandered” if they increase one political party’s advantage or provide what’s known as “incumbent protection.” The boundary lines often look strange. There is a long, sordid history of racial gerrymandering in the US, with maps drawn to increase or decrease the electoral influence of certain racial groups.

Sometimes districts are “packed;” that’s when the lines confine voters of a particular party or identity group into a small number of districts. In other cases they are “cracked,” when the lines spread voters across many districts to prevent them from forming a majority. Gerrymandering usually creates “safe” seats for the party that controls the redistricting process. This ends up making primary elections more crucial. Winning them can depend on appealing to a passionate base, a motivated faction within the dominant party. It’s a slippery slope to minority rule.

Gerrymandering has been contested in federal courts for decades. Racial gerrymandering was restricted by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But the partisan type has been more difficult to limit. In 2019, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Robert became involved. Opposition to voting rights legislation had been a central issue for him since arriving in Washington as an aide in Reagan’s Department of Justice. As Chief Justice, he ended hopes that the federal courts would help protect voting rights and create a national redistricting standard.

In the North Carolina case called Rucho v Common Cause, he wrote the decision for a 5-4 majority, ruling that partisan gerrymandering presented political questions beyond the reach of federal courts. Going forward, that would leave it up to plaintiffs in lawsuits to prove that any harm they experienced stemmed from something beyond party affiliation. In some states, nevertheless, partisan gerrymandering has been prohibited and some maps have been struck down.

Heather Cox Richardson explains in Democracy Awakening how redistricting and gerrymandering have made elections less free and fair since 2010. That’s the year Republicans launched Operation REDMAP, “a plan to take control of statehouses across the country so that Republicans would control the redistricting maps put in place by the 2010 Census.” New technologies enabled the GOP “to shift into overdrive.” The goal was to halt Obama’s agenda “by making sure he had a hostile Congress.”

And it worked. After the 2010 elections, Republicans controlled the legislatures in key large states — Florida, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Ohio, and Michigan, as well as several smaller ones. They redrew the maps “using precise computer models, essentially hobbling representative democracy,” argues Richardson. Even though Obama won re-election in 2012, Democrats still had a US Senate majority, and received 1.4 million votes more for House candidates, Republicans won a 33-seat majority in the House of Representatives.

In 2021, Democrats used redistricting to claim seats in Illinois, Maryland, Oregon, Nevada and New Mexico. Already having an edge, Republicans took four seats in Florida and worked the margins in Texas, Tennessee, Indiana, Oklahoma, Georgia and Utah. According to the nonpartisan Brennan Center, thanks to gerrymandering the GOP had a 16-seat advantage.

Both parties now understand that increasingly partisan state courts are not likely to block partisan power plays. In New York, a Democratic court allowed Democrats to remake the map before 2024. In North Carolina, the state supreme court upended a fair map and reversed a year-old decision banning partisan gerrymandering as soon as Republicans took control. They drew themselves three extra seats and a 10-3 advantage. That number matches the current Republican House majority.

In recent years, gerrymandering has insulated hard-right lawmakers from election challenges, allowing them to enact conservative policies on reproductive rights and public education that are actually rejected by majorities of voters.

But Donald Trump wants more. In Texas, he has requested a redistricting map that will guarantee him as many as five additional seats in Congress. If that happens, California will probably retaliate with a mid-decade redistricting plan of its own.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has tweeted that California will “draw new, more ‘beautiful maps,’ they will be historic as they will end the Trump presidency (Dems take back the House!).” Common Cause, which opposed gerrymandering and partisan redistricting for years, has announced that, for now, it won’t oppose Democratic states that want to use it in response to Trump’s “calculated, asymmetric strategy.”

Other blue state governors are also talking tough. But Republicans have more targets, including Ohio, Missouri, Indiana and Florida. Trump’s goal is to stay in control of Congress — regardless of what a majority of voters want.

The “fighting fire with fire” approach makes Democratic arguments ring a bit hollow, however. It’s harder to call someone a “cheater” — and Trump certainly cheats, even on golf — if you do the same thing. No matter which side gerrymanders or where it happens, the result is that some group of politicians is manipulating the vote to guarantee themselves victory. One party wins, but democracy loses.

Meanwhile, more people lose faith that their representatives are defending their constituents’ interests rather than their own positions and privileges. Of course, gerrymandering isn’t the only problem; voter suppression, the filibuster, and the electoral college also dilute the power of voters. But gerrymandering undermines the incentive to build broad coalitions. Instead, it reinforces the idea that the outcomes of most elections can be predicted.

As Yascha Mounk concludes in The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and How They Can Endure, “this sounds dystopian to me.” A democratic election in which the outcome is known in advance leaves a sour taste, and countries or states in which one party predominates for decades tend to suffer from pervasive corruption.

“Obama once said that we shouldn’t slice and dice the electorate into blue states and red states,” Mounk recalls. In the short term, that may seem like the best we can do. But it’s not a very attractive vision for the future of democracy.