Editor’s Note: This video report was published by African Stream.

Mali bans French-supported and -funded NGOs from operating within its borders.

Editor’s Note: This video report was published by African Stream.

Mali bans French-supported and -funded NGOs from operating within its borders.

This article originally appeared in Peoples Dispatch.

Sixty years ago, on May 25, Ghana’s first prime minister and president, the anti-colonial revolutionary leader Kwame Nkrumah stood before 31 other heads of African states in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa and declared, “[T]he struggle against colonialism does not end with the attainment of national independence.”

“Independence is only the prelude to a new and more involved struggle for the right to conduct our own economic and social affairs…unhampered by crushing and humiliating neo-colonialist controls and interference.”

“We must unite or perish,” Nkrumah had emphasized, recognizing that while countries across the African continent were “throwing off the yoke of colonialism,” these successes were “equally matched by an intense effort on the part of imperialism to continue the exploitation of our resources by creating divisions among us.”

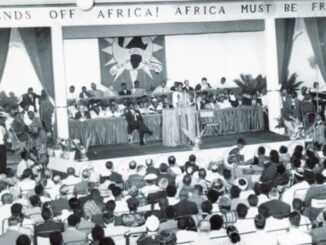

Nkrumah was speaking at the founding of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, striving, alongside other leaders, to build a Pan-Africanist vision of a continent united under a common currency, monetary zone, and central bank, and a united government and joint defense under an African High Command.

That these conditions did not materialize speaks to imperialism’s “intense effort” to suppress this vision. The coming decades would see African leaders assassinated and overthrown in coups backed by colonial powers for daring to envision a life of dignity for their people. Meanwhile, international financial institutions, dominated by these very forces, implemented brutal regimes of structural adjustment, sinking African countries further into debt and exploitation.

While the OAU eventually became the African Union (AU) and the African Liberation Day became Africa Day, May 25 still serves as a crucial day for progressive forces to connect the struggles for national liberation and Pan-Africanism of the 20th century to the present struggles against imperialism.

On this theme, Pan African Television hosted a discussion titled, “African Liberation Day: The State of the Struggle for Freedom” on May 25.

Recovering the History of Collective Liberation

The general secretary of the Socialist Movement of Ghana (SMG), Kwesi Pratt Jnr. added, “The national liberation struggle is not over…even if that struggle was over… what about the ownership and exploitation of our resources for the sole purpose of enriching the bank accounts of the multinational corporations in the colonial metropolis?”

“The radical nature of this celebration [of African Liberation Day] is saying that we as African people came together to end exploitation…end colonialism…to continue to strive for stopping neocolonialism from taking its root on the African continent. That struggle is still ongoing,” said Kambale Musavuli, a leading activist and an analyst with the Center for Research on the Congo-Kinshasa.

“In some parts of the African continent, people still do not have independence…The people of Western Sahara are still under colonialism by Morocco. We have to make sure that they are liberated.”

African Liberation Day also recognizes that people across Africa threw off the yoke of imperialism through collective struggles. Dr. Vashna Jagarnath, a labor activist and director of Pan Africa Today, commented. “We all know the struggles we face 60 years later, we have been recolonized in different ways, through the debt crisis, through foreign policy, through military bases being allowed to be built on our continent and determining to us who it is we can have relationships with, that determine our local policy…”

“Our continent is in a crisis. So we need to recall our history of us liberating ourselves.”

The Addis Ababa meeting of 1963 had been decades in the making, preceded by the Pan-African Congress held in Manchester, UK, in 1945 and the All-African People’s Conference in Ghana in 1958. However, these initiatives were also built on hundreds of years of struggle by the African people for freedom, “a part of the long march” from the days of the transatlantic slave trade, Pratt stressed.

This long history of liberation struggles and their collectivist orientation is not widely known by young people across Africa today, Musavuli said, calling this an “erasure of history.”

In reality, collectivism had closely informed the period of the struggle for independence for the DRC, and this took various forms—including the support provided by other African countries like the Central African Republic to the DRC. We must remember the fact that Pan-African activist T. Ras Makonnen had helped to get Patrice Lumumba to Ghana in 1958 and how the Mau Mau had gone from village to village in the country and screened films in 1960, Musavuli highlighted.

“The independence of Congo was not a national affair, it was a continental affair…We cannot talk about June 30 as Congolese independence, it was a Pan Africanist independence,” he said, reiterating the need for unity and a “Pan Africanism of the people.”

Internationalist Oppression, Internationalist Resistance

Speaking to the historic erasure of these links in the context of South African exceptionalism, Jagarnath said, “You are taught about the South African economy as if it is divorced from the rest of Africa, as if South Africa, which is a resource-rich country, is rich on its own, as if it was not migrant labor workers from Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi working in our mines, without getting any compensation, to enrich the elites of our country.”

Even today, “for the South African capitalists who are exploiting and benefiting from Ghana… Why must they worry about the liberation of Ghanaians? They don’t need to tell Africans the role of Ghana in the history of our liberation… That is a dangerous story that will affect their profits.”

At a time when African Liberation Day is barely celebrated on the continent, including in Nkrumah’s own country of Ghana, Jagarnath noted that the reason was because the “political project had changed”.

“We as people give up our power to those in power and we let them dictate to us, and they change, and the changes that come into place are economic and political…they do not want us to be liberatory because if we have liberatory policies…if we remember the liberatory aspects of our history we will try to liberate ourselves from them, and this is not convenient because they are now making deals with each other to continue to exploit this continent.”

“So we have two sets of exploitation: the classical imperial exploitation that still comes from the imperial nations, but we also have our internal systems.”

It is this very nature of exploitation that determines that the form of struggle must be internationalist: “The struggle for national liberation in Africa has always been an internationalist effort,” Pratt said. He elaborated that this was due to the fact that the very division of Africa had been an internationalist effort, namely the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, when colonial powers partitioned the African continent among themselves for the purposes of extraction and exploitation.

“Our enemies are united, and we have no chance of succeeding against that united force if we [ourselves] refuse to unite,” he said. There is a rich history of this internationalist unity, not just within the continent. Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara set up a camp in Ghana to train fighters who were engaged in parts of Eastern Africa and South Africa. The internationalist unity was also reflected in Cuba’s armed support in the fight against apartheid and the consolidation of the independence of Angola and Namibia, Pratt added.

We can also see this in the connected struggles for Black liberation in the United States and the liberation against imperialist oppressors on the African continent, stated panelist Makayla Marie, a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation in the United States.

Internationalism remains a necessity today, the panel discussion emphasized, “You cannot support the independence of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic without supporting the struggle of the Palestinian people for national independence against apartheid colonial occupation,” Pratt added.

“What we are fighting is the scourge of capitalism in its worst forms, at this imperialist stage, and we need to unite as African people…as socialists…as revolutionaries to achieve victory, which is inevitable.”

This was also underscored by Musavuli in the case of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where “it is not just imperialists but also other African countries, who are exploiting the country … They are only able to do it because they see the DRC as separate. They do not see us united in the struggle.”

These issues inevitably lead to a key issue that the panelists addressed—that of a general crisis of political legitimacy of current governments and of the use of divisive politics which worked to obscure the common reality “that we are all oppressed by the same oppressor,” as Marie said.

“People, be it in the U.S. or the African continent, have a difficulty right now choosing their leaders, and they must unite and challenge the forces that be,” Musavuli stated. This necessitates the need for mass-based and mass-led collective struggles for a “true independence,” the panelists reiterated.

“These Western countries after colonizing us, enslaving us, and stealing our resources, are now coming back to us and telling us that if we want to develop, we have to be like them and follow the capitalist path to development. That path started from slavery, passed through classical colonialism, and has today arrived at neocolonialism,” Pratt said.

“We have arrived at a situation in history where the only viable option available to us is the self-reliant path to development, the ownership of our resources for our own development… and that option inevitably leads us to the path of socialism.”

“Socialism is the only path to liberation from exploitation, from oppression, from poverty.”

Editor’s Note: The following was originally published in Black Agenda Report.

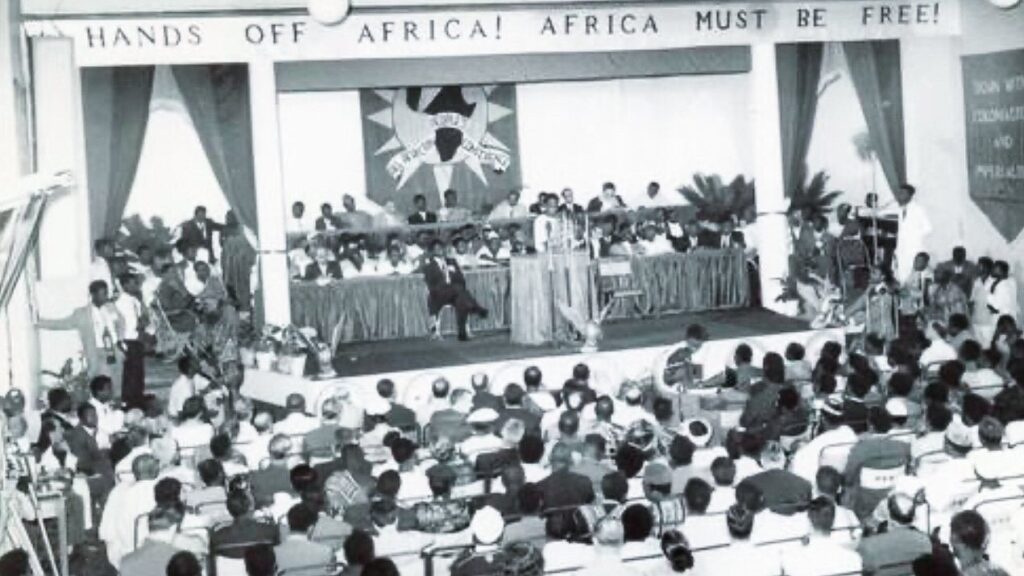

On March 24, 2023, Randall Robinson died at the age of 81. In his many obituaries, he will be remembered as a “human rights advocate, author, and law professor,” as well as “founder of TransAfrica,” and author of The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks. Robinson became a household name after the organization he founded in 1977, TransAfrica, spearheaded public protests against South African apartheid in front of the South African embassies in the early 1980s, helping to give voice to the international anti-apartheid movement.

Once one of the largest African American human rights and social justice organizations, TransAfrica was founded on a vision where Africans and people of African descent are equal participants in the global world order. It took as a point of departure the belief that the freedom of African Americans is bound up with the “emancipation of all African people.” As such, TransAfrica’s mission was to serve as a “major research, education and organizing institution for the African-American community, offering constructive analysis concerning U.S. policy as it affects Africa and the African diaspora in the Caribbean and Latin America.”

For some of us, what we remember most about Robinson is his enduring support of Haiti and Haitian people. He supported Haiti’s reassertion of sovereignty and democracy with the 1990 election of Jean Bertrand Aristide. After Aristide’s first overthrow—after only seven months in office—by a U.S.-backed coup d’etat, Robinson waged a 27-day hunger strike to both force the reinstatement of Aristide and to protest racist U.S. policies against Haitian migrants.

Perhaps the most enduring memories of Robinson’s steadfast support for Haiti and Haitian people come with the phone call to Democracy Now, in the early hours of March 1, 2004, after U.S. marines and the U.S. ambassador to Haiti, Luis Moreno, went to Aristide’s house and forced him and family members onto an unmarked plane that then flew them out of the country. Robinson said:

“[Aristide] called me on a cell phone that was slipped to him by someone… The [U.S.] soldiers came into the house… They were taken at gunpoint to the airport and put on a plane. His own security detachment was taken as well and put in a separate compartment of the plane… The president was kept with his wife with the soldiers with the shades of the plane down… The president asked me to tell the world that it is a coup, that they have been kidnapped.”

Robinson remained a friend of Haiti. He flew with U.S. Congresswoman Maxine Waters to the Central African Republic, where Aristide had been dumped by U.S. special forces, to intervene on his behalf. Readers can learn much more about this ordeal in Robinson’s 2008 book, An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President. Robinson also wrote a number of other important books, including Defending the Spirit: A Black Life in America; The Reckoning – What Blacks Owe to Each Other; Quitting America: The Departure of a Black Man from His Native Land; and two novels: The Emancipation of Wakefield Clay and Makeda.

In 2001, Robinson permanently left the United States to move to St. Kitts, the Caribbean island from which hailed wife, Hazel Ross-Robinson. He had become disillusioned with the retrograde, unjust, and incorrigible U.S. political system:

“America is a huge fraud, clad in narcissistic conceit and satisfied with itself, feeling unneeded of any self-examination nor responsibility to right past wrongs, of which it notices none.”

To mark Robinson’s passing and to remember his legacy, we reprint below a 1983 interview from Claude Lewis’s short-lived journal, The National Leader. The interview foregrounds Robinson’s deep understanding of global Black politics and the sharpness of his anti-imperialist analysis–especially concerning the role of the U.S. as the world’s hegemon. Robinson’s analysis, alongside his courage, his integrity, and his love of Black people, will be missed.

Randall Robinson: Third World Advocate

TransAfrica is a Washington-based lobby organization that often takes strong, progressive positions on African and Caribbean questions. Randall Robinson, a Harvard trained lawyer and farmer Congressional Hill staffer, is executive director of the six-year-old organization which now has 10,000 members. During an interview with Managing Editor Joe Davidson he castigated President Reagan for “the vileness of this administration’s policy toward the Black world” and the close relationship between the United States and South Africa, “the most vicious government this world has seen since Nazi Germany.”

Joe Davidson. How would you assess the level of involvement of the Black community in foreign affairs? Many people have complained over the years, or at least we have been stereotyped over the years as having interest only in domestic issues. What’s your experience?

Randall Robinson: I think it has changed fundamentally in the last 30 years. The post-civil rights movement, foreign affairs activity of the Black community has shown a dramatic increase of interest, and I think that is in large part because we’ve made some gains and we can think about some other things so that we don’t have to dwell so much on domestic concerns, but we can still monitor and express ourselves on domestic concerns and at the same time be involved in foreign policy concerns. I think it was a myth and untrue to suggest in the first place that we were not interested in foreign affairs. One looks back through the record; you can go back as far as Martin Delany, and Frederick Douglass, and Garvey, and James Weldon Johnson, and the NAACP, through the ’30s and before, to show a strong interest in foreign affairs. People like Alpheus Hunton in the ’30s and ’40s, and W.E.B. DuBois, of course, were instrumental in their foreign affairs involvement. I think there’s a more general popular involvement now on the part of the Black community and certainly on the part of Black institutions. I can’t think of a single Black national organization that at its annual convention does not take a position on a variety of issues, particularly those concerning U.S. policy toward Africa and the Caribbean.

JD: A number of people have expressed, informally, some dismay that there was not more of an outpouring of protest—on the street protest—against the Grenada invasion. Do you think that the level of protest against that was up to what you would expect or up to what you would want?

RR: I think it was up to what we would expect. There are a variety of reasons for that. It was a very complex situation and I think protest in the United States may have exceeded protest in the Caribbean itself. One has to remember that polls in Grenada – well not in Grenada but in Trinidad and In Jamaica and other places – showed that by and large Caribbean people supported the invasion. The question is “Why and why were there not more protests in the United States?” First of all, I think that one cannot diminish or underestimate the impact that the killing of Maurice Bishop had on the levels of protest that we saw expressed in the wake of the invasion. The killing of Maurice Bishop, and Jacqueline Creft, and Unison Whiteman and the others were at first met by extreme reactions of anger, including my own. Maurice, Unison and others involved were both personal friends, political colleagues, and people who were very decent, idealistic human beings who dedicated their lives to the betterment of the lot of their people in Grenada. And they were summarily executed by people who took it upon themselves to wrest power away from those in whom it was duly vested. So, the Reagan administration saw an opportunity—with the successors to Bishop stripped of support—to invade; and they took that opportunity. There were many in Trinidad and Jamaica who were interested in seeing Maurice avenged without thinking about the implications of the act of the avenger. In addition to which many were confused by the invitation on the part of the Eastern Caribbean States to have the United states join with them in the invasion. So, all of these things served to muddle public reaction in the United States. Particularly given the fact that most Americans don’t know very much about anything west of Los Angeles or east of Washington, D.C. And ignorance, coupled with affection for Maurice, the barbarity of the action of his and his cabinet ministers’ elimination all taken together made for a dampened reaction to the invasion in the United States.

JD: What should be done now with Grenada? The invasion is fait accompli, it’s history, Maurice Bishop is dead; he can’t be brought back. What do you think should be done now?

RR: Well I think first, Maurice can’t be brought back, but as (former Jamaican Prime Minister) Michael Manley told me in a long discussion we had two weeks ago, “This may have produced a hundred Maurice Bishops.” Maurice Bishop did not live in vain; he left a sterling record of accomplishment and commitment to be emulated in time to come. And one has to believe that in Grenada itself, a few years from now, that Maurice Bishop having been martyred will arise as a memory and life model to be cherished by young Grenadians. I think that the first thing to do is to get the United States out and to get a self-determination of that nation’s sovereignty restored and democratic institutions restored. I don’t mean democratic institutions certainly in the way that Reagan and his people mean them, but institutions in which Grenadians themselves broadly participate in ways they see fit, meeting their own needs. So that means getting the U.S. out. That means to have the government that follows on not bullied into this policy or that policy by the mammoth to the north. The reason the U.S. invaded is what causes us concern in the first place. We know the invasion had nothing to do with the safety of American lives, but had everything to do with the Grenadian leadership not doing what they were told to do; for developing friendships as self-determination prerogatives allow nations to develop, with Cuba and with the Soviet Union but also with Europe and with the Western Bloc. Grenada was truly non-aligned. One must fight to preserve for future Grenadian government the same prerogatives of self-determination and sovereignty. It is up to them and them alone to determine what kind of political and economic system that they want to have and what kinds of relationships they want to develop with countries in the region and outside of the region, Eastern or Western Bloc countries. And failing that, what we have is a de facto restoration of colonialism in Grenada. We in the United States who are concerned about these things must make certain that the United States is not allowed to de facto re-colonize that country.

JD: You hosted Maurice Bishop in this country in May. There was a big dinner for him, your annual dinner at which he spoke. During that visit, he also met with members of the Reagan administration. It had been suggested by some that he was attempting to move closer to the United States. Is that true?

RR: He was attempting to develop a rapprochement with the United States in the same fashion that Cuba and any number of other nations in the hemisphere have attempted to do. “Move closer,” suggests that he wanted an alliance with the United States different from their friendships with other countries. They wanted normalized relations, they wanted trade, they wanted a diminution of the hostility that existed between the two countries. His trip here was an olive branch and he was rebuffed. He came and asked for a meeting with President Reagan (and was) refused, asked for a meeting with Secretary (of State George) Shultz and was refused, and was offered a meeting with the American ambassador to the OAS, Mittendorf – of course that was a rather gratuitous and harsh slap in the face to have a head of state meet with the American ambassador to the OAS – and in the last analysis he was given a meeting with William Clark, the National Security Council advisor and was rebuffed in that meeting. So that the Maurice Bishop that the Reagan administration now describes as “the martyred of the New Jewel Movement” was put in a position of weakness by the same administration that refused to normalize relations with him. Maurice did not want a lopsided foreign policy that saw him locked into relationships with eastern countries without relationships of the same sort with western nations. Certainly the Europeans responded in a sensible fashion, because the airport there and their development program have been assisted by the British and the other European economic community countries. Only the United States, the big bully of the hemisphere, treated Grenada in this fashion.

JD: Let’s move across the ocean to southern Africa. The Commonwealth nations, including two members of the contact group—the western contact group, Canada and Britain—recently said that the United States is at fault for there being no settlement to the Namibian question. This is something that you have said for a long time. “The issue of the Cubans in Angola is a phoney issue,” you’ve said and others. But now because the Commonwealth and because members of the contact group are coming out and saying that too, do you think it will change Reagan administration policy on Namibia?

RR: No, I don’t think anything will change Reagan administration policy. The only way to change Reagan administration policy is to get a new tenant at the White House, and we’ve got to dedicate ourselves to making sure that’s done next year. First of all, one has to make clear that the Reagan administration never had the independence of Namibia at the top of its agenda. That was simply a sort of smoke screen behind which the Reagan administration was cultivating a closer relationship with the Republic of South Africa. South Africa in Reagan eyes, of course, is the guardian of Western interests in that part of the world. And so the United States is much more concerned about the containment of what it calls “the spread of communism” in southern Africa than it was about the interests and freedom of the people of Namibia. They’ve been subordinated. And if there were, two months ago, any chance of persuading the people of Angola that they could do without Cuban assistance I think the invasion of Grenada completely dashed any faith they might have in U.S. good faith. The Angolans have asked for a long time should they send the Cubans home. The Cubans, who together with their own forces, are all that stand between them and a South African toppling of their government. They’ve asked who would help them with their security concerns, who would protect them from South African troops; and the United States has now answered by demonstrating that it has no more concern for the sovereignty of a small developing nation than do the South Africans. So how is the Angolan government in Luanda to put any faith in any assurances that come out of Washington after this nation has violated the OAS charter, the United Nations charter, international law, and its own domestic law in invading Grenada in the way that it did?

JD: Chester Crocker, the assistant secretary of state for African affairs, sees constructive evolutionary change in southern Africa. At the same time, the policy of constructive engagement has brought about an increase in cross-border raids, an increase in forced relocations and a general crackdown on the opponents of apartheid including recently a number of whites who have been supportive of the aims of the African National Congress. The relationship between the Reagan administration and South Africa appears to be firming up apartheid. Is there anything that can be done other than getting the Reagan administration out to change that?

RR: Mr. Crocker is not stupid. He sees South Africa with the same eyes that you do. South Africans are very pleased with the responses of this administration to its activities and clearly the administration in Pretoria has moved to the right both in its relations with its neighbors as well as in its domestic policy since the Reagan administration has been in power.

Again, let’s restate the basic premise here that the United States has no intention under the Reagan leadership of changing the configuration of power in southern Africa. It does not want to dramatically reshape the sort of power structure of South Africa. It likes it perfectly fine, likes white supremacy perfectly all right. Because it is that white leadership that is so virulently anti-Communist and so much in tune with Reagan geopolitical visions of how the world ought to be ordered.

I think one can do some things to temper this kind of right wing zealousness on the part of the Reagan administration before a turn in government, but that requires at the same time an enormous effort on the part of Americans to demonstrate their displeasure with this kind of alliance that these people have formed with the South Africans. At the same time there are a good many things, Joe, that we are doing with the Congress that the Reagan administration would be hard put to turn back. One, there’s the bill offered by Rep. William Gray of Philadelphia to prohibit any new American investment in South Africa. That is a part of the Export Administration Act. Now, that passed in the House. There is no counterpart language in the Senate Export Administration Bill. But we go to conference in January, on the bill; and to keep the language in we have to persuade the Senate conferees, particularly a Republican or two, that this language is important to us. Now once we get this passed, it would be very difficult for the Reagan administration or President Reagan to veto the Export Administration Act.

One of the key people that we have to sway on this, on the conference committee is going to be Senator (John) Heinz of Pennsylvania. So we have to concentrate our lobbying on Senator Heinz and the others who are going to be on that conference committee to let them know how important this legislation is to the Black leadership and sensitive white leadership in this country. In addition, there’s the Solarz Bill that does one thing I’m not particularly interested in and opposed, but two things I very much support. It would codify, make mandatory the Sullivan Principles. Now, Rev. Leon Sullivan and I have worked very closely together on a number of things. We just happen to disagree on the strength and importance and usefulness of the Sullivan Principles. But he supports the Gray Bill and has been shoulder-to-shoulder with us on prohibition of new investment. In addition to which the Solarz Bill would prohibit the sale of Krugerrands, South African gold pieces, in the United States and would further prohibit American bank loans to the South African government. So those are two important elements of that legislation. This is also a part of the Export Administration Act and in conference we have to retain this.

We can’t have two of the elements chipped away with just the Sullivan Principles left standing. Again, Senator Heinz and others will be important in this context. Lastly, of course there is the IMF (International Monetary Fund) bill that we are going to see as a part of it anti-apartheid language. Not the language that we wanted which would mean no support possible for any American vote for an IMF loan to South Africa. But we do have language now that calls for a demonstration from the administration that South Africans have taken action to significantly reduce apartheid before getting such a loan and calling upon the South Africans to go into the private capital market before going to the IMF in the first place, and then requiring the Treasury—the Secretary of the Treasury—21 days in advance of any intent to vote for a loan for South Africa to come to the Congress and to demonstrate that these conditions have been met. Now, President Reagan will have to sign the IMF bill.

So what I’m suggesting, Joe, is that there are some things that we’ve been able to do through the Congress as parts of bills that the administration wants that net some real progress for us. But in terms of expecting anything more from this administration, of an anti-apartheid fashion; no, we’d be dreaming to expect that. These people very much favor what’s going on in South Africa.

“Randall Robinson: Third World Advocate,” The National Leader: The Weekly Newspaper Linking the Black Community Nationwide 2 no. 32 (December 15, 1983)

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by The Grayzone.

Ilhan Omar was greeted with vigorous booing during a July 2 Minneapolis concert featuring Somali singer Suldaan Seeraar in Minneapolis. The booing was so profound and so sustained that it was impossible to mistake it for cheering, or all the thumbs down for thumbs up. It reportedly went on for ten minutes or more, punctuated with, “Get out!” and “Get the f*ck out of here!”

Ilhan smiled, gesturing at the crowd to tamp it down, as though the adulation was just too much. Her husband, Tim Mynett, stood at her side looking awkward and confused, then someone who seemed to be a concert manager gestured at the crowd more emphatically to tamp it down. Some say the booing went on even longer while Ilhan went through the process of presenting Suldaan Seeraar with some sort of award.

The singer shifted uneasily from one leg to another, seeming startled and unsure what to do, then reached out to gesture at the crowd, also asking them to tone down their gestures of disapproval. This seemed to be more than he had bargained for when he agreed to share the stage with the congresswoman.

Congresswoman Ilhan Omar was booed last night by thousands of the Minneapolis Somali community last night at a Somalia Independence Day celebration concert.

“Go home! Go home!” pic.twitter.com/40TPX4M4NA

— Rebecca Brannon (@RebsBrannon) July 3, 2022

Seeraar is extremely popular in the Somali community and was playing to a packed house; he’s unaccustomed to boos. This was his first concert in North America and he’s likely unfamiliar with Ilhan’s record in the House and on the House Foreign Affairs Committee’s Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, and Global Human Rights, where she serves as vice chair. (Karen Bass currently chairs the subcommittee, and vice chairs the National Endowment for Democracy, the regime change wing of the U.S. government, and is all but certain to become the next mayor of Los Angeles come November.)

Ilhan, an African immigrant and the only Black person on the subcommittee besides Bass, is a shoe-in to become chair if Democrats hold onto the house, unlikely as that may seem.

Many Africans shudder at the thought, however –– not only in Somalia, her country of origin, and the rest of the Horn of Africa, but also in the African Great Lakes Region and in diasporas from both regions.

When I organized a Twitter space discussion with Somali American activists on Ilhan’s record, I heard an outpouring of anger not only over her perceived neglect of her district, where violent crime is surging, but also over her role in the removal of Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed and her support for a candidate affiliated with her personal clan. This was but one of examples of the congresswoman’s role in advancing U.S. meddling in the Horn of Africa.

Ilhan Omar Meets with Kagame and Tedros As They Plot Against Ethiopia

In October 2021, Ilhan traveled to Rwanda as a guest of its authoritarian president and war criminal Paul Kagame, a darling of global elites. She then proceeded to vote against a House resolution to call on Kagame to free political prisoner Paul Rusesabagina.

In Rwanda on a private visit, Congresswoman Mrs @IlhanMN stopped by our offices today, for a presentation of the Foundation and other programmes, initiated by Our Chairperson @FirstLadyRwanda. pic.twitter.com/HNQBffJDy1

— Imbuto Foundation (@Imbuto) October 9, 2021

David Himbara, a former economic advisor to Kagame, and Tom Zoellner, author of Rusesabagina’s biography, slammed Ilhan in a Minnesota Post op-ed, writing that her relationship with Kagame threatened “to throw her entire stance on the U.S. criminal justice system into a light of hypocrisy.”

With regard to the Ethiopian civil conflict, Ilhan has directed her criticism squarely at the government, even as it defends Ethiopia from attack by the U.S.-backed Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which ruled the country brutally for 27 years, from 1991 to 2018, and waged war against Eritrea.

On April 7 of this year, the congresswoman met with former TPLF Foreign Minister Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to “discuss global health security challenges, including the status of the global COVID response, the global hunger crisis, and ways to improve digital technology to broaden healthcare access.”

Yesterday, we met with @DrTedros to discuss global health security challenges, including the status of the global COVID response, the global hunger crisis, and ways to improve digital technology to broaden healthcare access. pic.twitter.com/VfifvVrcSL

— Rep. Ilhan Omar (@Ilhan) April 7, 2022

Tedros has relentlessly abused his global platform as Director of the World Health Organization, in violation of UN rules about political neutrality, to advocate for Tigray — home of the TPLF — as though it were the only Ethiopian region suffering the consequences of the war. He never mentions the immeasurable suffering caused by TPLF invasions of Amhara and Afar Regions, both of which I traveled through in April and May.

After Ilhan’s meeting with Dr. Tedros, members of the Ethiopian community unsuccessfully demanded that they release the minutes of the meeting.

On several occasions, Ilhan has asked the State Department for “legal determinations” as to whether the Ethiopian government is guilty of atrocities. Meaning, in fact, illegal determinations, because the assumption she has advanced is that the U.S. has the right to rule that international crimes — most of all genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity — have been committed and action must be taken, as in Libya and Syria. According to international law codified in the UN Charter, only the UN Security Council can do that.

On December 21, 2021, while questioning Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee, Ilhan requested an illegal “legal determination” regarding Ethiopian atrocities, called for an arms embargo on Ethiopia, which would make it unable to defend itself, and proposed a “carrot and stick approach” to bringing Somalia to heel.

Ilhan Omar Backs Cold War-Style Measure to Bully African Nations Into Submission

On April 27, Ilhan voted to pass H.R. 7311 – Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act, along with all the rest of the House Democrats and all but nine Republicans. H.R. 7311 directs the executive branch to bully African nations with sanctions and withdrawal of foreign aid if they get too close to Russia, and to “invest in, engage, or otherwise control strategic sectors in Africa, such as mining and other forms of natural resource exploitation.”

The House passed H.R. 7311 roughly two months after 17 African countries either voted to abstain or did not vote on a UN resolution condemning Russia for invading Ukraine, and Eritrea dared to vote no. The African states voting no comprised just over half of the 35 UN member nations that opposed the measure.

House Resolution 6600, a harshly punitive bill that would sanction Ethiopia and Eritrea, is now pending in the House Foreign Relations Committee. According to Ilhan’s constituents, she has not spoken out against it, although she did make a splash by voting against the embargo on Russian oil.

Why Was Ilhan Omar Booed at Suldaan Seeraar’s Minneapolis Concert?

This writer joined a July 6 Twitter space opened by Somali American community organizer Abdirahman Warsame; 294 Somali Americans and a few Somalis — despite the distant time zone — joined the space. Many of the Somali Americans participating were from Ilhan’s Minneapolis district, and some of the younger ones had attended the concert.

Abdirahman told me that activists with the #NoMore Global Movement for Solidarity in the Horn of Africa had planned to get a few front row seats at the Suldaan Seeraar concert to boo Ilhan and that once they started, it was like a match in a haystack.

Everyone in the Twitter space was furious because Ilhan did her best to help the U.S. displace President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, aka Farmaajo, whom they described as a decent, responsible, corruption-fighting anti-imperialist.

Farmaajo had joined Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki in signing the Joint Declaration on Comprehensive Cooperation Between Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia, which ended the long-running war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and promised a new day of regional cooperation between the three largest nations in the Horn of Africa. It said:

“Considering that the peoples of Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea share close ties of geography, history, culture and religion as well as common interests, the three countries shall build close political, economic, social, cultural and security ties. The three governments hereby establish a Joint High-Level Committee to coordinate their efforts in the framework of this Joint Declaration.”

That, however, was more peace and independence than the U.S. government could tolerate, as many on the Twitter space angrily confirmed. Now, with Farmaajo out of office, the alliance is considerably weakened. The peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea still stands, although the U.S.-backed TPLF keeps skirmishing with its troops on their common border, and Eritrea is helping Ethiopia in its civil war with the TPLF in Welkait.

Ilhan put an enormous effort into getting rid of Farmaajo in a parliamentary election, which many in this Twitter space said was actually clan-based and manipulated by bribery.

Last year, on December, she quote-tweeted a State Department threat to take action if Somalia did not hold elections immediately, stating: “Farmaajo is a year past his mandate. It’s time for him to step aside, and for long overdue elections to proceed as soon as possible.” Her comment was widely republished to make the case against Farmaajo in the U.S. press.

Farmaajo is a year past his mandate. It's time for him to step aside, and for long overdue elections to proceed as soon as possible. https://t.co/f08bSjOJrm

— Ilhan Omar (@IlhanMN) December 27, 2021

Both the president and the parliament were at that time in office past their constitutional terms. That made Farmaajo interim president, but the states of Puntland and Jubaland refused to recognize his authority. Elections had been repeatedly planned but postponed due to disagreements between parties and lack of election infrastructure. In addition, the Islamist Al-Shabaab was continuing to oppose the existence of a secular Somali state, and the U.S. was still bombing on occasion.

According to those in the Twitter space, Farmaajo had been fighting to establish a direct, one-person-one-vote electoral process to replace the corrupt system of parliamentary election. They said he would have won in a landslide had he succeeded.

As soon as Farmaajo was defeated on May 15 — even before the formal transfer of power — Biden announced a plan to reintroduce troops to Somalia. The New York Times reported the news without raising an eyebrow, but the fury expressed in the 194 reader comments was palpable.

Most commenters were Americans outraged that the U.S. would be introducing more troops anywhere after the Afghanistan debacle, but they also included this response by a Somali American (edited very slightly for punctuation and grammar):

Shakur Abdull

Columbus, OH May 17

Somalia’s federal government just re-elected former president Hassan Sheikh Mohamud less than 48 hrs ago.

The former president Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo, who was previously a U.S. citizen and resident of Buffalo, NY, has lost the election due to parliamentary bribery, corruption, and foreign nations’ interfering, spending millions of dollars to overthrow Farmaajo. Those nations included Kenya, U.A.E., & others.

It’s not surprising news to witness the Biden administration seeking to have U.S. military presence in Somalia, since Hassan Sheikh’s election because President Farmaajo would’ve opposed it. Furthermore, this move will only increase security risks and destabilize the Horn of Africa. Sending U.S. military troops now to Somalia is unnecessary, and those troops will be viewed as enemies to the nation and its serenity.

The Somalia army has been fighting Al-Shabaab and all terrorist activities within the region. The army are well trained by the U.S., Turkey, Eritrea, and so on, but the Somalia government is faced with an arms embargo which limits its abilities and its operations. If President Biden wanted to offer solutions or a hand, then the approach would’ve been totally different than resending American troops back into a hostile situation. Former U.S. President Trump’s hands-off position in foreign affairs was exceptionally appreciated.

Also as soon as Farmaajo was gone, and even before the formal transition of power, an oil and gas extraction contract with a U.S. corporation that Farmaajo had blocked was back in play.

The July 6 Twitter space on the booing of Ilhan Omar contained similarly angry commentary by Somali Americans about her imperialist foreign policy positions. After the discussion, several participants sent over the following pointed statements:

Deeqa, @Deeqa_lulu

I am a Somali woman and I think I would have obtained my rights and my future would have been better in Somalia if I had the opportunity to vote for President Farmaajo, but we didn’t have the one-person-one-vote system that he was trying to put in place. Ilhan Omar is originally from Somalia and she has a daughter my age who can vote for her own president in America. She says she believes in democratic principles and she’s a member of the Democratic Party, but she didn’t support a very important right for me, the right to vote in a one-person-one-vote election.

Is this about the Democratic Party or about U.S. foreign policy toward Somalia? Either way, I feel bad and frustrated that she hasn’t changed that. Why would I expect Joe Biden to understand my problem if Ilhan Omar doesn’t? I contacted my family in America and told them not to give their votes to the Democratic Party or to Ilhan. Our 2022 election here in Somalia was eye opener for us about the Democratic Party policy toward Somalia.

We want to vote here in Somalia. That’s one of my biggest dreams now. –Deeqa

Mohammed Caanogeel, @MCaanogeel1

Ilhan Omar is being used by the Democratic Party, whose foreign policy has been aggressive and counterproductive towards Somalia.

She got booed at the concert for two reasons:

Domestically, she promised the East African community help with gun violence and drugs in our community and she hasn’t helped us with that at all.

Internationally, she undermined our sitting Somali president, President Farmaajo, by tweeting and making speeches that he was no longer the president of Somalia even though the constitution of Somalia gave him legitimacy to continue until another president took over. She was helping the U.S. government undermine this president who had captured the hearts and minds of all Somali people.

Farmaajo enjoyed 90% popularity for good governance. This president introduced reforms into the economy to win debt relief from the IMF and World Bank, but Ilhan voted against debt relief here in the United States.

Farmaajo asked the U.S. to lift the arms embargo so that our army could fight the Al-Shabaab fundamentalists, but Ilhan refused to vote for that.

President Farmaajo was loved for his stability, transparency, and fairness. He made us proud by building the military and making our intelligence one of the top 10 in Africa. He built institutions back after 30 years of war, invited foreign embassies into Somalia, and established embassies abroad.

He became such a role model president that the Somali people bought him a home, library, and offices for future campaigns. Even poor people loved Farmaajo so much that they gave to this fund drive for him.

Ilhan joined U.S. policymakers in rejecting all his good deeds, rejecting what the Somali people wanted, rejecting one-man-one-vote, and instead threatened to cut off aid. She and the rest of the U.S. government seek only the worst for Somalia. As we write to each other, the U.S. military has overtaken Berbera Airport and brought a warship to Berbera shores. -Mohammed Caanogeel

Ilhan Ignores the Boos in a Safe Blue District

After the booing episode, Fox gleefully hosted Ilhan Omar’s Republican challenger Cecily Davis to mouth meaningless platitudes about how her opponent is “out of touch with her constituents,” claiming “they are ready for change and are seeking someone who represents their conservative values.”

Davis appeared to be completely ignorant about why an audience of Somali Americans might boo their Somali American representative. The same was true of other right-wing outlets who framed the booing as confirmation that Ilhan’s woke identity offends her own community and that their candidate was therefore a serious contender.

Shukri Abdirahman, a conservative Republican who previously ran to unseat Ilhan, also highlighted the congresswoman’s “woke” positions on social issues as a source of local resentment, but also made sure to point to Ilhan “becoming an election-meddling dictator in the foreign affairs of Somalia – a sovereign nation.”

🧵 Understanding The Booing

Ilhan Omar getting booed and being told to get the f*ck out by our Somali community is not just a revolt against Ilhan selling her soul to the devil and becoming an election-meddling dictator in the foreign affairs of Somalia – a sovereign nation. 1/3

— Shukri Abdirahman (@ShuForCongress) July 5, 2022

Abdirahman Warsame (no relation to Shukri) told me that some culturally conservative Somalis had told him they were uncomfortable with Ilhan’s defense of abortion and LGBT rights, but no one expressed that discomfort in the Twitter space.

Minnesota’s 5th District is the bluest in the state, so the incumbent merely has to win the August primary to win the election, and she is expected to, though perhaps not by the margin she’d like. However, the House is all but certainly turning red, so the next chair and vice chair of the House Foreign Relations Subcommittee will in all likelihood be someone other than Ilhan Omar.

Ann Garrison is a Black Agenda Report Contributing Editor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for promoting peace through her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes Region. She can be reached on Twitter @AnnGarrison and at ann(at)anngarrison(dot)com.

Copyright Toward Freedom 2019