Chile’s population rejecting a proposed constitution on September 4 will hit hard one group: Indigenous people, who are socially and economically disadvantaged, thanks to generations of land dispossession and invisibility in Chile’s political landscape.

Chileans voted against enacting a new constitution that would have replaced the one installed by U.S.-backed dictator Augusto Pinochet in 1980. The document—drafted by an elected body—was defeated with 62 percent voting against (“rechazo” in Spanish) and 38 percent in favor (“apruebo”).

Since 78 percent of Chileans had voted in favor of a new charter in 2020—shortly after a period of social unrest in 2019—the September 4 rejection shocked many. The defeat has halted the newly elected government’s progressive agenda, which would have granted greater gender parity, ecological and human rights.

“I’m sure all this effort won’t have been in vain because this is how countries advance best: Learning from experience and, when necessary, turning back on their tracks to find a new route forward,” said President Gabriel Boric, shortly after conceding defeat.

However, some have accused Boric of double talk.

The Death of Plurinationality

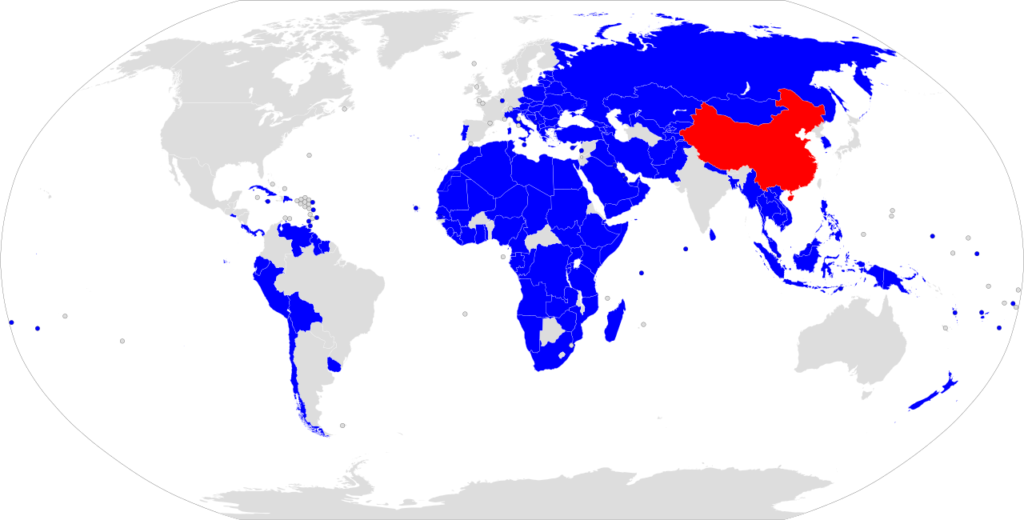

The new constitution would have recognized Indigenous people for the first time, which would have designated Chile a plurinational nation. Chile is the only country in Latin America that does not recognize the Indigenous population.

Cheers followed when the government declared Indigenous representatives would be included in drafting the constitutional document. Shortly afterward, Mapuche academic Elisa Loncon was elected to oversee the process.

The constitution would have also guaranteed ecological protections. Indigenous communities depend on natural resources to maintain their livelihoods and cultures. Their ancestral lands have been sites of conflict as multinationals plunder Chile’s natural resources for profit.

The Araucanía region, the site of conflict between autonomist Mapuche groups and forestry companies, had the largest proportion of rechazo votes at 78 percent.

The rejection serves the interests of big business in the region, and the forestry industry in particular. The Matte group (owners of CMPC), one of the wealthiest economic groups in Chile, funded the rechazo campaign along with the Angelini group that own Forestal Arauco (granted 1 million hectares by the Pinochet regime, expropriated from Mapuche and peasant landowners). The move has been profitable as shares in both companies have gone up by 20.88 percent and 5.82 percent, respectively. One of the top 10 donors to the Rechazo campaign was Italo Zunino Besier, owner of forestry company Virutas de Madera S.A. He gave 10 million pesos ($10,690).

Racist Narratives in the Reject Campaign

The othering of the Mapuche was instrumental for the Rechazo campaign, which capitalized on racist populism and encouraged anti-plurinational sentiment. Rechazo slogans such as “Chile es uno solo” (Chile is one) spread the idea that plurinationality would fragment the nation, while “We want peace” were direct references to the Mapuche struggle for autonomy and the troubles in Araucanía.

The neo-conservative think tank Instituto Res Publica warned, for example, that giving Indigenous communities a say would hurt the economy.

“An argument used by the right was that the constitution would create ‘Indigenous nations,’” Reynaldo Mariqueo, a spokesperson from Mapuche International Link, a non-governmental organization, told Toward Freedom. “According to them, the Mapuche do not constitute a nation and, therefore, should not be recognized as such. However, we maintain that the Mapuche are not just a nation, but a state.”

The Double Discourse of the State

In the run-up to the presidential election, Boric vowed to heal the rift between Mapuche people and the Chilean state.

“Militarization is the wrong path,” he told the Chilean press. “We must seek dialogue within a historical perspective. This conflict won’t be solved within the remit of ‘public order.’ We must restore confidence and talk about the territorial restoration of the Mapuche Nation.”

But, in July, he placed Araucanía under a military state of emergency. Then, on August 24, Chilean Investigations Police arrested radical Mapuche leader Hector Llaitul. He is leader and spokesperson of Coordinadora Arauco Malleco (CAM), which seeks autonomy from the Chilean state and the right to live on ancestral land in the southern territories of the region of Araucanía.

His son and other members of the CAM have also since been arrested. The detentions have outraged Mapuche leaders.

“For us in the Mapuche world and communities in resistance, the detention of Hector represents a maneuver by the Chilean right-wing supported by the government of Boric,” Richard Curinao, a Mapuche activist and Werken journalist told Toward Freedom. “This is evidently a strategy to curb the advance and control that these leaders and organizations, such as the CAM, whom Hector represents, and halt their expansion in Mapuche communities. And the success they have had in recovering territories, territories that have been usurped by the forestries.”

Juana Calfunao, chief of the Juan Pallileo community in the Aracuania region, is a founder of the Chilean non-governmental organization, Comisión Ética Contra la Tortura (Ethical Commission Against Torture). She accused the police of a “set-up.”

“For us, this is very painful,” Calfunao told the press. “We will defend [Llaitul] until the final consequences. We will defend our weichafe (warrior). We will defend anyone detained in this manner. There have been 140 years of the Chilean State and we will continue to defend ourselves and continue to survive and struggle and confront whatever lies ahead.”

‘Mapuche Convinced Only Way Out Is Emancipation’

Since the outcome of the referendum, Chile has been plagued with political uncertainty.

Gabriel Boric has shuffled his cabinet lurching towards the political center, and there has been talk of another attempt to write the constitution. But this time, Indigenous leaders have not been called to meetings.

Toward Freedom contacted press offices for Chile’s national government and for the Araucanía government, but did not receive a reply.

The majority of Chileans voted to maintain the status quo because they didn’t want to share a state with Indigenous people, Mariqueo said. Similarly, the Mapuche feel neither Chilean nor Argentinian, making plurinationality appear pointless.

“’Reject’ leaves things the way they are,” he added. “Except that, today, most Mapuche are convinced that the only way out (of the conflict) is emancipation from Chilean dominance, which includes—as a tool—the treaties agreed to by the Chilean and Spanish states and international norms, which preclude the creation of the Chilean state.”

Carole Concha Bell is an Anglo-Chilean writer and Ph.D. student at King’s College London.