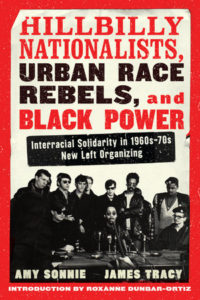

Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times by Amy Sonnie and James Tracy (Melville House Publishing, 2021)

“America’s radicals are a problem we can’t ignore,” goes the title of lawyer and activist Daniel Miller’s recent CNN.com op-ed. In it, he describes the dismay he felt on a trip to Civil War battlefields in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where he overheard visitors deride “woke people” wanting to tear Confederate statues down. Miller infers these people came for purposes other than championing the “American experiment” he holds to be true and dear. Reflecting on the uptick in white-supremacist and fascist violence in the United States, Miller concludes the solution to the “complex nature of the problem of radicalization” in the United States rests solely on institutional reform.

Like other liberal commentators, Miller mislabels racists and fascists as “radicals” in his op-ed, misplacing the white settler-colonial tenets the United States was founded upon. Those capitalist, colonial, racist and patriarchal principles are manifested in the white supremacy and fascism seen today. Thus, the culmination of this violence in the January 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol is not an aberration in or an affront to “American democracy,” but a reflection of the true history and nature of the United States.

This history often is hidden, but revealed in classic works like W.E.B DuBois’s John Brown, Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and Robin D.G. Kelley’s Hammer and Hoe. But generations of white radicals and true revolutionaries—most prominently working-class or poor—have stood and fought in solidarity with anti-racist, anti-patriarchal, anti-capitalist and anti-war movements against the U.S. state and its actors.

This true history of white radicalism contradicts liberal narratives like Miller’s, which look for solutions to racism and fascism in U.S. elections and institutions. All that said, the new 10th anniversary publication of Amy Sonnie and James Tracy’s pathbreaking book, Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power—which expands upon the history of radical poor white people’s interracial solidarity organizing—could not have come soon enough. By the book’s end, Sonnie and Tracy prove beyond a doubt poor whites have been and can continue to be a part of progressive multiracial social movements—or “rainbow coalitions.” Their book reveals a history that contradicts long-held beliefs that poor white people in the United States are hopelessly racist and unable to organize beyond their immediate needs.

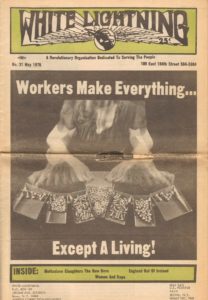

Divided chronologically into four chapters, the book profiles five groups: JOIN Community Union of Chicago; the Young Patriots and Rising Up Angry, also of Chicago; the October 4th Organization of Philadelphia; and White Lightning of the Bronx, New York. Sonnie and Tracy detail how these radical organizations of the 1960s and ‘70s built off each other to develop unique forms of multiracial collaboration and interracial solidarity “in step with the revolutionary internationalism and socialism of the original Rainbow Coalition” (p. xxxi).

In the first chapter, the JOIN Community Union, or JOIN, initiated by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1963, is upheld as an embodiment of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Chairman Kwame Ture’s call for white activists to “organize their own” in commitment to the radical race and class politics of the Black Power Movement. Based in Chicago’s Uptown section, also known as “Hillbilly Heaven” because of the area’s large numbers of displaced white Appalachian families, members led welfare committees, housing strikes, political education programs and much more inspired by the politics of the Black Panther Party.

The account of Peggy Terry’s radicalization also serves to highlight the leading role poor whites can play in forging radical multiracial alliances. Terry was one of JOIN’s most prominent members and would later embark on a nationwide vice-presidential campaign.

Later in chapters two and three, the Young Patriots and Rising Up Angry—both formed largely by members of JOIN shortly after its dissolution—would emerge on the scene to build upon the tradition of poor white radical organizing in Chicago. Perhaps, most famously of all, the Young Patriots, comprised of “dislocated hillbillies” (p. 64), would go on to form the first-of-its-kind Rainbow Coalition led by Fred Hampton and Bob Lee of the Black Panther Party, along with the mainly Latinx-led Young Lords, in an attempt to consolidate their class struggle.

Launched later in 1969, Rising Up Angry was similarly formed to revive a culture of radicalism in white working-class communities. Like with the previous groups, Rising Up Angry’s formation was not easy. The organizers encountered internal contradictions and struggles regarding racism, sexism and class-divides in their communities. However, Sonnie and Tracy do well to show how Rising Up Angry especially made strides through co-leadership initiatives, women’s groups and internal criticism toward an intersectional politics committed to doing more than treat these serious issues as mere “add-ons” (p. 129).

The final chapter takes the reader east to Philadelphia and New York, where the October 4th Organization and White Lightning operated respectively throughout the 1970s. During a period of immense right-wing backlash to leftist organizing, and against even greater odds, these groups carried on the legacies of radical groups prior. By further situating their struggles and conditions within the broader context of global capitalism and imperialism, it took only a small, dedicated cadre to usher in “the kind of personal–political transformations that ultimately sustain people as lifelong radicals” within their largely white working-class immigrant communities (p. 181).

This crucial history of radical organizing that Sonnie and Tracy uncover shows it will take “both patience and diligence” to make progress in poor white communities (p. 71). The authors make it clear the radicalization will not occur overnight.

However, this does not mean the authors are not optimistic. The way they vividly write about the groups and individuals spotlighted throughout their book does much to inspire a radical hope for the future of organizing in today’s poor white communities. When liberals like Daniel Miller mistake white supremacists and fascists for white “radicals,” they are mislabeling those on the far-right today. As Sonnie and Tracy remind us, that only seeks to uphold the United States’ legacy of racism and colonization.

Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power uncovers the long-hidden and oft-forgotten history of poor white radical organizing on the Left during the 1960s and ‘70s. As the reader makes their way through this revelatory book, it is clear Sonnie and Tracy not only have made an important scholarly contribution, which builds upon the radical histories uncovered by those before—like W.E.B. Du Bois, Howard Zinn and Robin D.G. Kelley. More importantly, the authors have provided a valuable tool for radical working-class and poor white people organizing in the U.S. Left today.

Patterson Deppen serves on the editorial board at E-International Relations, where he is editor for student essays. He is a member of the Black Alliance for Peace Solidarity Network and the Overseas Base Realignment and Closure Coalition (OBRACC). His writing has appeared in TomDispatch, The Nation, The Progressive, E-International Relations and other outlets.