We met on the morning of March 7, under an overpass in the south of Ciudad Juarez. Heavy urban traffic braked and buzzed on either side of the gathering. Dozens of women burned a bra, sang together, and wheat pasted images of men accused of assault to the concrete blocks supporting the street overhead. The local media snapped pictures, supportive men stood back and watched.

The women stepped on to the streets and did a short warm up, moving their bodies together, stretching from head to toe. Then they took over the boulevard, lining up between a pawn shop and a mattress store, and began to march.

The most vocal wore black, with glints of purple and green. Almost all of them were masked up. But their masks and handkerchiefs had nothing to do with COVID-19: they hid their faces out of fear of state violence and retaliation for their ongoing participation in autonomous feminist struggles.

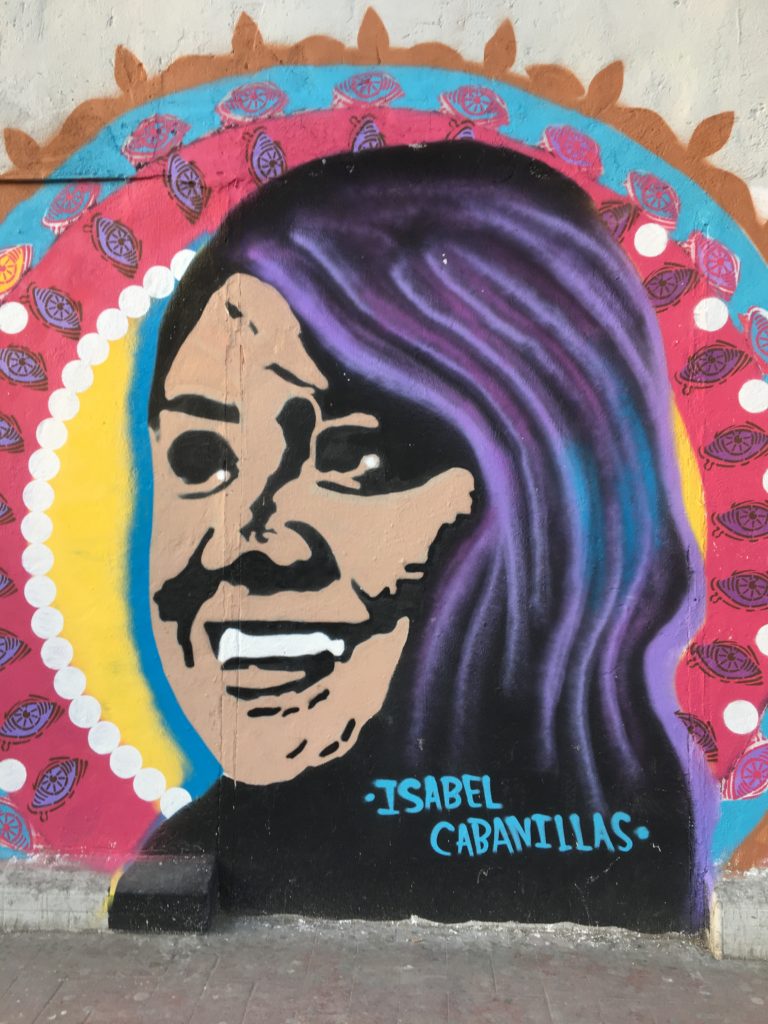

The fear felt by women in Juarez deepened in January, when Isabel Cabanillas was shot twice while cycling home from a popular downtown bar frequented by artists and leftists in the Mexican border city. A well known local artist, Cabanillas participated in numerous activists groups, including Hijas de su Maquilera Madre, a feminist collective whose name translates as “daughters of maquila worker mothers.”

Members of the Hijas de su Maquilera Madre collective and other friends of Isabel Cabanillas say there may be a connection between Isabel’s murder and her activism against a Canadian mining company with plans to mine copper in the Samalayuca Desert.

Multiple women I interviewed named a local man supportive of the mine who had previously come into conflict with Cabanillas as a potential suspect. But because local and state police have not exhaustively investigated the crime, we do not know for sure who Isabel’s killer was, much less his motives.

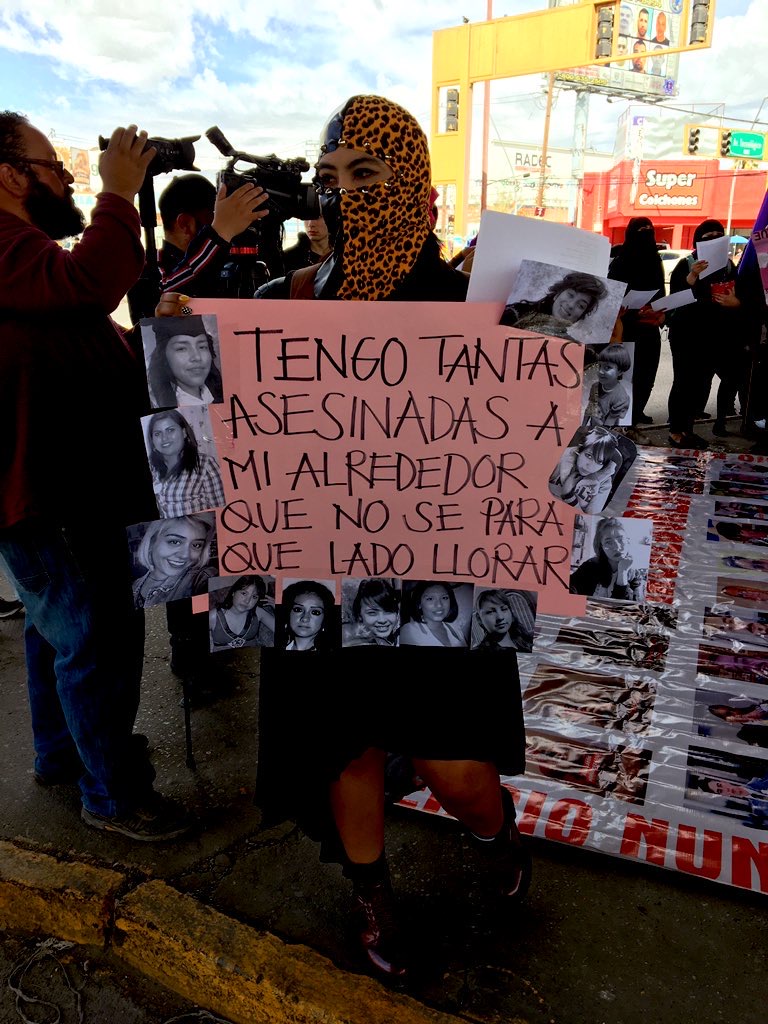

“During Isabel’s funeral we were looking at each other, and I think all of us, cause we talked about it later, we thought, ‘When are they going to kill us,’” said Huitzi, her face covered by a keffiyeh. Like the other women I interviewed that day, she asked me to change her name to protect her identity.

A veteran activist and feminist, Huitzi has been working for change in Ciudad Juarez for decades. The killing of Cabanillas brought back painful memories of the death of her friend Susana Chávez, a poet and activist who was murdered in the border city in 2011.

Huitzi said she’s still in the streets because protest is the only way for women to demand safety and justice for missing and murdered women. I asked her about the decision to be on the streets on March 7, a day ahead of International Women’s Day.

“The NGOs live from the state, and they kneel before the state,” she said, referring to a divide among groups based on how more mainstream women’s organizations in the city handled the killing of Cabanillas.

Various women I talked to in Ciudad Juarez said that the proximity between the largest women’s organizations and prosecutors made them privy to information about Cabanillas’ murder. But, the women said, that information was not shared in a transparent manner.

Earlier this year, Red Mesa de Mujeres, a women’s organization funded by USAID and the EU, convened a March 8th demonstration. This is why a smaller group decided to get out ahead and march the day before.

The divide between grassroots collectives and larger, better funded organizations has been aggravated since Isabel’s killing, but it isn’t new. Some trace its beginnings to almost a decade prior, in the context of the caravan for peace led by Javier Sicilia, which created controversy when it arrived to the city in 2011. Back then, autonomous groups pushed for demilitarization, while Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) signed on to a more watered down agreement.

Under the high desert sun, nearly two hundred women marched down the boulevard in a commercial district of the border city. Some of them banged pots and pans, others cried out in call and response chants: “The oppressive state/is a macho rapist.” Family members of victims of violence led the march, followed by collective members and women, and then men and women who are part of gender-mixed collectives.

The march went past a paint store and a group of women darted in and emerged shaking fresh cans of spray paint. When we arrived in front of the sprawling headquarters of Channel 44, the women sprayed the walls with tags calling on the TV station –owned by the powerful Cabada family– to properly report on femicides in the city.

In the first three months of this year, over 400 people were killed in Juarez; and in April alone there were over 155 murders in the city, of which at least 24 of the victims were women.

I asked Paola, a 22 year old nurse from El Paso who attended with her sister, why she decided to march. “I’ve felt threatened so many times when I’ve been in the street, and I see all the women being disappeared and I’m afraid it could be me, or my sister, or my mom,” she said. She wore a white dress covered in red handprints. Her head was wrapped in a t-shirt, a strip of forehead visible above her aviators.

“I remember the first time I was afraid, I was in elementary school, I went to elementary school here in Juárez, and we heard about what happened to this girl named Estrella: she was cut into pieces, and dumped into a barrel which was filled with cement, and I remember that day I felt very afraid to be a woman, since I was little.” In her hand was a can of spray paint and a hand painted sign that said Justicia.

The March 7th action ended at a vacant lot known as Campo Algodonero, where a spare, low plaque commemorates the victims of femicide whose bodies were found there years before. The mothers of these young women brought a case before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica. In its ruling, the court found that since 1993, the government of Mexico has been responsible for structural violence against women in Ciudad Juárez.

Despite the divisions, it is apparent to all that these conditions of structural violence still exist today.

The next morning, a march set out from the pink cross set up at the Paso del Norte crossing in downtown Ciudad Juarez, crossing part of the city’s downtown before reaching a small city park. Gone was the blaring sun, in its place a low grey sky.

Local journalists said the March 8th event was the biggest International Women’s Day (IWD) march they’d seen, with thousands of women, including migrants and trans women, women on horseback and others in wheelchairs or scooters, moving slowly through the city’s urban core.

Women police officers lined the sidewalks and pigeons swooped overhead. At one point a freight train loosed a series of loud whistles as it rolled past, provoking a swell of cheers and whistles from the crowd.

But the effusive energy of the march quickly dissipated as leaders and representatives from the city’s most established women’s groups climbed up on a large stage and began making speeches.

Many of those in attendance drifted over to a nearby plaza, which typically plays host to an alternative Sunday market where artisans and vendors sell jewellery, records, and fresh baked bread. The young women who had organized the march the day before had set up a cultural event, timed to coincide with the official speeches. They denounced state violence and demanded justice for Isabel, as many hundreds of women raised their right fist.

The IWD activities in Ciudad Juarez were but the northernmost link in an increasingly powerful chain of women led protests, strikes and demonstrations that are changing the face of politics and social movements in the hemisphere. Marches took place in cities throughout Mexico.

In Mexico City, some women were gassed as they attempted to reach the city’s central square. Dressed in purple, from above they looked like a continuation of the jacaranda trees whose flowers float lilac above the streets in the spring.

In the nearby city of Puebla, thousands and thousands of women streamed into the central square, their actions coming on the heels of an unprecedented inter-university strike and mass action against the murder of four medical students and their Uber driver in February.

In Monterrey, Guadalajara and other cities, women led and organized marches were also bigger than they were the year previous, and women also gathered in smaller cities around the country.

“I see women in Mexico becoming more radicalized, in these past years we’ve seen that women are more organized, even here in the city, young women, women in high school and middle school are calling out aggressors in their schools, and that makes us very happy,” said Sirena. We talked in the plaza after the March 8 cultural event had wound down.

The next day, on March 9, the federal government promoted a day without women, a confusing brand of protest during which women were encouraged to stay home. Some employers even gave women a day off, even though Mexican women average six hours of unpaid work per day, much of it inside the home.

Less than two weeks later, authorities would be asking all Mexicans to stay home. Little economic support has been provided to the millions of people who work in the informal economy around the country. Violence against women has spiked, and in Juárez, workers went on strike to demand safer working conditions during the pandemic.

On May 5th, Isabel’s birthday, members of Hijas de su Maquilera Madre and Mujeres en Rebelión wheat pasted her image in the street, together with more than 70 drawings and photographs made in her honor. Dressed in t-shirts painted with handmade slogans and wearing handkerchiefs and N-95 masks over their faces, it is women who continue to demand justice and forge a path forward in these complicated times.

This is the second report from Toward Freedom’s América Feminista series. Next week we’ll have a story about feminist movements in Uruguay.

Author Bio:

Dawn Marie Paley is a journalist and editor of Toward Freedom. She’s the author of Drug War Capitalism. Follow her on Twitter @dawn_.