“No Trump! No KKK! No Fascist USA!”

That chant has echoed through the streets of the United States with increasing frequency since the November 2016 election of Donald Trump. Maybe you’ve even lost your voice screaming it alongside hundreds of others.

Green Day helped introduce it to the world at the 2016 American Music Awards, but the band was building off a similar chant pioneered by their punk rock elders MDC, whose 1982 song “Born to Die” starts off with vocalist Dave Dictor’s original chant: “No war/No KKK/No fascist USA!”

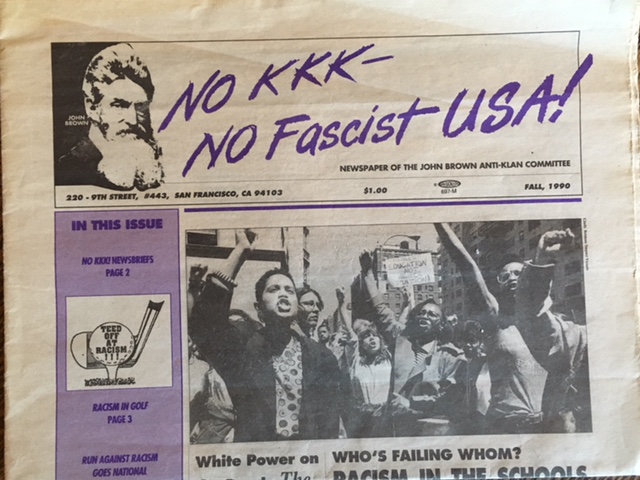

MDC was one of the most prominent bands to support the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee throughout the 1980s. This support included playing benefits shows for the committee to be able to spread their message and continue confront and stop racists in the streets and in their communities. These shows would also include JBAKC literature available to distribute. And the San Francisco chapter would eventually changed the name of their newspaper to No KKK! No Fascist USA!

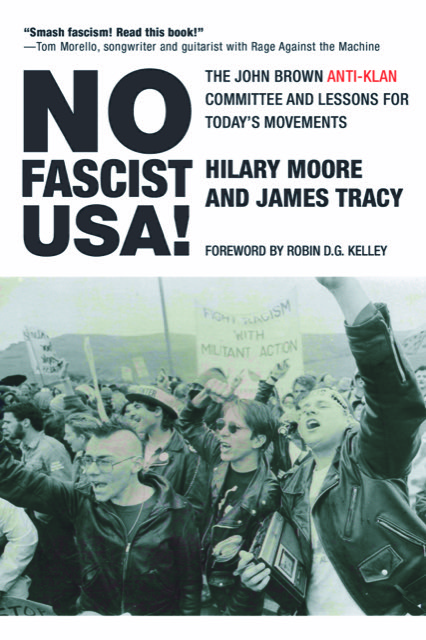

Thirty years before Trump would do the same, Ronald Reagan’s Republican administration helped embolden the Klan, neo-nazis, and other far right extremists throughout that decade. But as authors Hilary Moore and James Tracy brilliantly demonstrate in their new book No Fascist USA! The John Brown Anti-Klan Committee and Lessons for Today’s Movements, during the Regan era there was a determined nationwide movement that fought back.

Accompanied by a foreword by renowned movement scholar Robin D.G. Kelley, the book traces the organization’s rise in the 1970s and its evolution through the early 1990s in the continued struggle for collective liberation. And it draws on archival materials and new, original interviews conducted with former members of the committee in order to present their full story. The text is beautifully complimented with photographs, posters for anti-Klan actions, and clippings from the group’s various newsletters throughout each of the chapters.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with Hilary and James about this history and its potential lessons for current movements against white nationalism and the fascist creep—in the USA and beyond.

Matt Dineen: First off, how did this book come together as a collaborative project? How did you decide to combine forces to unearth this history of antiracist and antifascist struggle in the US? And why did you focus your research on the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee (JBAKC)?

Hilary Moore: In the summer of 2016, I went with a group of friends to my hometown of Sacramento, California to protest against a joint demonstration of the Traditionalist Worker’s Party and the Golden State Skinheads—two white supremacist organizations that were attempting to conjure support during Trump’s presidential campaign. I worked with Catalyst Project at the time, as an anti-racist political education trainer. It made sense to me that, given the onset of racist support for a Trump presidency, we would mobilize to confront this form of white supremacy in the streets.

On the grounds of the state capitol, I saw multiple people on our side stabbed by white supremacists. I saw horse-mounted police protect these same white supremacists by ushering them into the halls of the capitol building. This really fucked me up.

I spent the next weeks trying to find elders in the movement who had done confrontation work before, hoping to learn from them. I was eager to learn what worked and what didn’t. Linda Evans was one of the first people I talked to. She’s on the advisory board for Catalyst Project and was a member of the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee in Austin, Texas.

My conversations with her and other JBAKC members showed me that there was a very rich, under-explored part of antifascist movement history in the United States. After I did a few interviews, I wanted to talk with James about the questions that were coming up. We agreed all of it was worth studying in more detail, so we decided to do this book together.

James Tracy: I’ve been fascinated by the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee since 1989 when they came to my hometown to mobilize against the Aryan Woodstock/White Power concert organized by the White Aryan Resistance. I was drawn to them by their uncompromising stand against white supremacy and their bravery.

I was a part of the Punk and New Wave scene in the area, booking shows and being part of a few bands. The JBAKC seemed willing to go toe-to-toe with the racists, and I respected that a lot. Several of the local Nazi skinheads were stationed at the nearby Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

Despite my utmost respect for JBAKC, I was always a little conflicted about the organization. I wasn’t sure if their politics could be of use in convincing a few of my friends who were attracted to white supremacy to go the other way.

In 2011, I co-authored a book called Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times with Amy Sonnie. As a result of that, I met Hilary, who is a working-class organizer who immediately impressed me with her analysis and work ethic. We became fast friends, and I always knew that I wanted to do some sort of project with her. We worked together on some talks with Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz called “White Trash: Up For Grabs,” to address the ways the left related to white poverty.

At one point over drinks, she asked me if I would work on a book about the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee with her. For me, it was a no-brainer, of course I would.

MD: I really appreciate these personal connections you both have to this subject. I also appreciate how the book presents this history through a critical lens. Can you talk about some of the strategic shortcomings and mistakes of the JBAKC? And what are the most important lessons to be learned from their organized confrontations against white supremacy, particularly in this current political moment under Trump, for antifascists today?

JT: In order to understand this, you actually have to grasp one of their biggest strengths. The JBAKC and other organizations of their time understood that the system of imperialism shaped domestic politics. They insisted that the movement not only grapple with this, but support self-determination of Black and Brown communities.

They were absolutely on-point to insist that the left not turn away from the consequences of organizing within an empire, existing on stolen land. Like most radical organizations of the time, there was a drive to define what the “primary contradiction” in society was. I appreciate the rigor of this approach.

At times, it can lead organizations to a static place where it is easy to diminish the roles of other oppressions as well as the potential of organizing to inspire people to jettison white supremacy. Yet, JBAKC was absolutely right in insisting that there could be no lasting justice under continued imperialism.

But the main lesson for me is drawn from another one of their strengths: the need to oppose and confront organized fascism and racism. Have the back of your comrades especially when it is difficult to do so. And never, ever, talk to a Grand Jury!

HM: To that point, I will add that the JBAKC rarely talked about why they themselves, personally, were taking action. This choice, rightly so, comes from the fact that they so thoroughly centered their anti-imperialist politics, like James said.

Supporting movements for self-determination was seen as the most important point, not people’s personal stories. On the other hand, we know that personal stories about how we get into anti-racist work and what keeps us in movement for the long haul, is often what brings new people in.

So, there’s a contradiction here: centralizing a politic and being able to do so in a way that speaks to what people find meaningful. Honestly, I wish our movements today had a touch more of the JBAKC flavor of centralizing politics and principles. I think this would help some within white anti-racist movements today, to move away from an overly simplified identity analysis.

MD: Let’s take a step back and look at the origins of the organization and the larger context of the late 1970s. Can you talk about some of the groups, this sort of radical lineage of the New Left, that JBAKC grew out of? Also, what was the role of prison solidarity organizing in helping kick things off in the first place?

HM: A very short answer to this complex question is that many of the revolutionaries of color, with whom the folks that would later become the JBAKC were connected to, had been surveilled, harassed, incarcerated, or assassinated by the U.S. government’s COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) strategies during the 1960s and 1970s.

This meant that the state targeted leaders within Black Panthers, Black Liberation Army, American Indian Movement, Puerto Rican Independence movements. This move dramatically shifted the terrain of struggle. On the outside, many people lost hope as leader after leader was killed. On the inside, revolutionaries were pivoting from within prison walls shaping self-determination politics in the 1970s and 1980s.

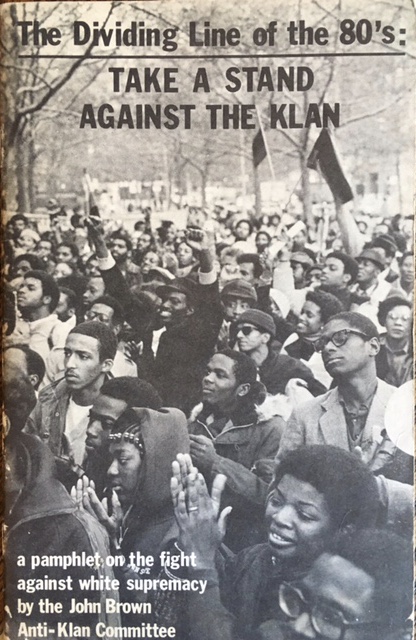

Lisa Roth, one of the founders of the JBAKC, speaks to this in chapter one: that what began as anti-racist work in the 60s and mid 70s morphed into political prisoner support work. From prison these same revolutionaries sounded the alarm on the Klan’s role—surveillance, harassment, threats, attacks—within the NY prison system.

In 1977, a man named Hodari, a former Black Panther, sent a letter to those doing support work for people incarcerated, asking them to put external pressure on the prison system for their collusion with Klan activity. This was the original call that sparked the emergence of the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee.

JT: I see the formation of JBAKC as one way that veterans of the 60s New Left tried to continue their politics as the New Right consolidated power in the late 70s and 80s. Various members had roots in the Civil Rights Movement, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), The Weather Underground and many other parts of the movement.

It was a moment when the reforms of the New Deal and Civil Rights Movements were coming under sharp attack, revolutionary prospects few, and the organized racist far right was emboldened. It’s a different context to mobilize in than just a decade earlier. From the beginning, JBAKC never saw fighting the far-right as an end to itself. Rather, it was a necessary step to be able to organize for liberation.

MD: I’m curious about what it was like documenting this history, particularly in terms of navigating the language of anti-racist and anti-imperialist politics. Throughout No Fascist USA!, you directly address this in footnotes; noting for example your decision to use the term “incarcerated person” rather than “prisoner” and a number of similar examples. Can you speak to this question of evolving nature of movement language?

JT: When writing a book the changing nature of language is always a challenge to navigate. The words we use today reflect current understandings of position and power.

We erred in favor of using terms that remind the reader that they are reading stories about human beings. You can bet that within a few years of publishing a book, some of the terms you used before may be seen as out-of-date.

HM: Yeah, language was definitely a tricky component we revisited often. We decided to keep terminology of the times intact when we pulled direct quotes from the JBAKC’s newspaper, event flyers, or articles from movement organizations. We changed terms when it seemed necessary to help readers grasp the lessons ripe within the history. For instance, it felt important to change the term prisoner to ‘people incarcerated,’ building relevance with the lines forwarded by today’s anti-racist movements against mass incarceration.

We ran into similar questions about the use of ‘fascism’ and ‘racism’ during this moment in history. We learned that the JBAKC could move fluidly in their description of fascism referring to state power, white supremacist street violence, and the role of policing and prisons at different moments, all within one term.

This works given the analysis they were bringing—there are different arms of empire that operate within a similar supremacist framework. Our job was to tease these things apart for the reader, so they could better understand what the organization meant more clearly. I think this tendency in anti-racist movements still happens today. As long as we get precise in our analysis, there’s utility in drawing out the continuities of structural, cultural, and systemic violence.

MD: Ok, thank you both!

For more information about the book and updates about Hilary and James’ now postponed tour visit: https://nofascistusabook.org/

Author Bio:

Matt Dineen lives and writes in Philadelphia where he also coordinates events at Wooden Shoe Books & Records, an all-volunteer anarchist collective founded in 1976.