On October 6th, the Chilean government, led by President Sebastián Piñera, increased public transit fares by four per cent in Santiago. Student led protests began immediately and continued as more people joined and supported the mobilizations and the government refused to revert the increase.

By October 15th, authorities decided to close some key metro stations in order to avoid massive fare evasions, but students and other protesters brought the bars down and entered the stations by force. Older people encouraged the students to continue protesting.

The closing of key subway stations located near or in downtown affected mainly the working class, who depend on public transportation to reach their jobs. In the midst of protests, the reaction of Piñera and his government has been to criminalize protesters and ignore their demands.

“Someone who leaves earlier and takes the subway at seven in the morning has the possibility of a lower rate than this one,” said the Minister of Economy Juan Andrés Fontaine. The minister was referring to the fact that the increase of fares was only applicable during peak hours (from 7-9am and 6-8pm). In the government’s view, if workers wanted to access a lower fare they need to adapt their working hours.

The minister’s claim created discontent among the population, since many workers and their families in Santiago already spend at least two hours a day on transportation. The only type of housing that is affordable is far away from central areas, which means workers have to wake up and leave for work when it is still dark. Asking them to wake up even earlier and to leave work before peak hours showed the government’s complete lack of empathy, as well as their failure to acknowledge the social conditions of workers.

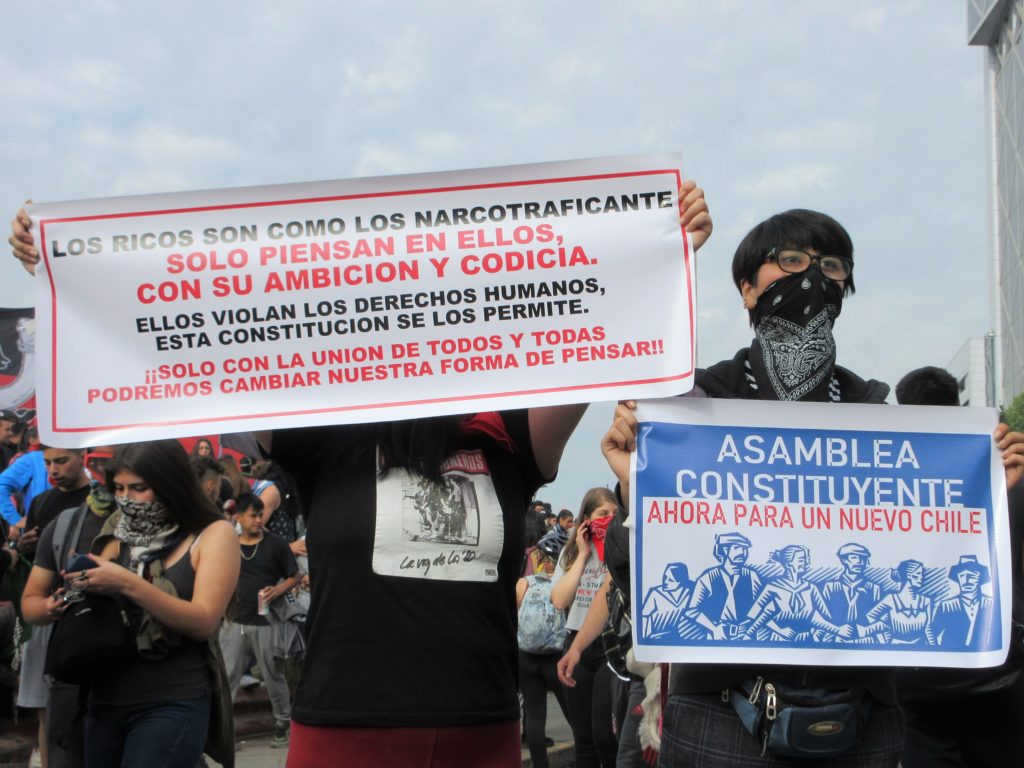

Spirits rose, and Chileans began to stand up to the government as a massive group. The streets became a battlefield. “We’re at war against a powerful enemy,” said Piñera. Under the slogan of “it’s not about 30 pesos, it’s about 30 years,” the demands of the protest against transit fares shifted to a broader protest against the neoliberal system. Later, that slogan transformed into “It’s not about 30 pesos, it’s about 500 years,” in reference to how colonialism is the system that initially created present-day inequality between Chileans and Indigenous peoples.

In the streets of Santiago today, most demonstrators do not belong to any particular political party or organization, rather, they are students, workers, feminists, older women, families, and otherwise. Anger and discontent towards the president and his government have overwhelmed the authorities. Such was the power lived on the streets that on October 18, Piñera declared a State of Emergency, which gave more power to the military. A related curfew lasted one week.

As Chileans continue to mobilize, their demands have grown: make water utilities public, establish a minimum wage of $676 a month, enshrine a 40 hour workweek, end corruption, reverse the hike in transit fares, reduce the wages of politicians, create a new Constitution, cancel a new free trade agreement, and demilitarize Wallmapu (the ancestral land of the Mapuche people).

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which was initiated by the centre-left ex-president Michelle Bachelet, was approved by the Chamber of Deputies in April of this year. This is a Free Trade Agreement that has at its center policies of privatization and deregulation, which enshrine corporate privileges and foreign investor rights.

Once the TPP was implemented in Chile it immediately created unease among the population, because it only benefits corporations and the elites that belong to the 1%. Students from University of Chile, the Metropolitan University of Educational Sciences and the University of Playa Ancha organized strikes, assemblies and protests on April 16th and 17th, when the TPP was approved.

Freedom for Mapuche people is also a key element in this current struggle that has put the wenufoye (Mapuche flag) above even the Chilean flag. The relationship between Chileans and the Mapuche is a complicated story of much suffering. Mapuche territory has been under military occupation for decades, and Mapuche people have been accused of terrorism, been murdered and been imprisoned.

Historically, the vast majority of Chileans have not actively engaged in support of Mapuche struggles. It is so powerful to see the wenufoye flag at the height of the movement in Chile today. There have also been banners in the marches saying: “Forgive us, Mapuche people, for not believing you. Now we know who the real terrorists are.”

On October 29th, Mapuche communities organized a large march to protest in support of the demands of Chileans. The current movement has joined together groups from different backgrounds, all fighting back against decades of abuse, impoverishment and inequality. This is part of why this movement doesn’t have specific leadership: it’s just people having each other’s backs and struggling together.

As the protests continued the energy grew and new ways to protest were added to massive fare evasion: supermarket looting, fires in subway stations and buses, cacerolazos (groups of people making noise with pots, pans and other utensils), and performers and artists disobeying the curfews to display and perform their work in the streets. The continued mobilization in the streets brought military and police repression, leading to police brutality, deaths, and hundreds of people being injured and arrested.

Since the protests began, Chile has experienced the worst human rights violations and state violence since the dictatorship, which lasted from 1973 to 1990. According to information from the National Institute of Human Rights (INDH), since the protests began 43 children have been victims of human rights violations which includes abuses, arrests and beating, 1,500 people are currently in hospitals because of the injuries, around 150 people have fully or partially lost their vision because of buckshots. There have been 18 reported cases of rape, and at least 18 deaths, as well as reports of torture in police stations. Thousands of people have been arrested by police and military officers just in the city of Santiago.

The situation on the streets is even worse that what these numbers tell us, as official statistics do not include unreported crimes. Paula Sierra, a Chilean feminist and doctor, has been on the streets helping the injured in the protests and collaborating with the INDH and the National Medical School. “I was disappointed to hear the INDH because the numbers they were giving were far away of what I was seeing on the streets,” said Sierra in a phone interview with Toward Freedom. “The president of the INDH was absent, so we the workers were very frustrated and wrote a letter against him. I mean, I saw the folks who suffered awful cases of oral, genital and anal rapes by officials right after they happened, and [INDH President Sergio] Micco was not saying a thing about it.”

What it is clear so far is that the government has used a discourse of delinquency to talk about demonstrators. This criminalizes and delegitimizes sociopolitical and economic demands made by workers, students, feminists, and professionals. “I call all our compatriots to join this fight against crime,” said Piñera on October 20th, referring to the protests as criminal activity.

Piñera has only acknowledged this movement and its valid demands once, on October 25th, the day the biggest marches took place in different cities from north to south. On that day in Santiago alone, more than a million people were in the streets.

The reaction of the president and his government was to cynically celebrate the peaceful protests and to introduce a New Social Agenda, which includes a series of reforms that do not address the protesters demands or promote structural change to neoliberal model. At the same time, the state repression throughout this period has not been addressed and the victims have not received any justice.

It is worth recalling that during Chile’s transition to democracy after the dictatorship, which ended in 1990, there have been a series of mass mobilizations.

The biggest one was the student revolution that we started as high school students in 2006, which reached its peak in 2011 when university students and families joined. After years of marches, protests, occupations of schools and universities, we remained without our basic right to free, quality education. In Chile, the working and lower middle class often have to go deep into debt to access education, as I did.

Pensions are a second important demand that have led Chileans to take to the streets multiple times over the years, demanding an end to the Chilean Pension System (AFP). The movements have demanded that the pension system be nationalized, and that retirees be provided with an income equivalent to a living wage, or about $676.

The minimum wage in Chile is currently $389 a month, and half of those who have taken a pension received less than $182 monthly. This system forces elders into poverty, as they have to live on less than the minimum wage. All the while, the ex-wife of a politician is eligible to receive a monthly pension of almost $7,800.

The privatization of pensions and education were measures started during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, which have become more entrenched over 30 years of right-wing and center-left governments.

The mass protests in Chile have made clear that the crisis is a crisis of the neoliberal economy. It has (re)politicized a population that was either too divided to protest or too scared of rising up because of the constant criminalization of activists. Today, with all these protests and calls to change the neoliberal system and the country at a structural level, Chilean and Mapuche people know there is a big challenge ahead: to organize and plan what comes next.

Assemblies are taking place all over the country, especially in Santiago, to discuss a new constitution and begin to imagine a new Chile, in community and from a plurinational perspective. “The main demand across all assemblies I’ve participated is the process for constitutional assembly, to start building a new constitution,” said Valentina Pineda, a geographer and member of the collective Ciudad Feminista. “Participatory processes have also been a common topic in the sense that they must be binding. The pension system, ecological issues and education have been fundamental demands we well.” She added that, in the ongoing uprising, “there have been a lot of anti-colonial perspectives, which has never happened within a social movement as big as this one in Chile”.

Among the different sorts of assemblies that have taken place in Santiago are the assembly organized by Colo-Colo, the biggest sport club in Chile, which brought together around 2,000 people; regional assemblies which gather people from each territory; feminist assemblies, such as the one Valentina Pineda participated in, which focus on the right to the city; and a women’s only assembly organized to discuss the authorities disdain towards feminist demands.

“We discussed about the recognition of all bodies and people who have the right to inhabit the city, which has been built by and for man. We think the city must be inhabitable, secure, and free of harassment for everyone,” said Pineda of the women’s only assembly. Pineda added that regarding the feminist movement as whole, “the most common actions have been against sexual violence that many comrades have experienced, whether in the streets or in the detention centers. Not only women have been victims of this but also people from the LGBTQ+ community.”

Even the Chilean diaspora has organized assemblies around the world in cities such as Mexico City, Austin, Texas, and Edinburgh, Scotland, among others. The call is to keep fighting to imagine and create a more empathic, fairer, equal, and collaborative Chile, where everyone is included and their basic needs are met with dignity.

Author Bio:

Pilar Villanueva-Martinez is an activist of the women’s movement in the global south and regularly writes about social struggles in Latin America for national and international media outlets.