International Women’s Day in Guatemala City marked a day of remembrance, but it also saw a flurry of action against abusive men in universities, state institutions and social movements. In the months previous, the country experienced a powerful #MeToo style movement denouncing violent men; and activism in defense of land and territories, led by Indigenous women, continued to challenge extractivism, racism and colonialism.

As women, trans and gender non-conforming people marched through the city on March 8th, some marchers handed out flyers warning others of abusers in their midst. Others broke away from the march and spray painted slogans against violence. Others yet diffused conflicts with churchgoers using street theater and art.

At the end of the march, a solemn vigil remembered the 56 girls who were victims of a fire at the Virgen de Asunción group home.

“In Guatemala, like everywhere else, there are many new expressions and ways that women are looking after each other, and defending each other, even from the organizations and feminist movements, which have historically have treated other forms of organization –especially that of Indigenous women– as though we were below them,” said Jovita Tzul Tzul, a Maya K’ich’e lawyer based in Guatemala City.

During the march “we denounced not only harassment and violence, but also all the other kinds of violence that we as Indigenous women are facing, from the issue of evictions to the criminalization of our struggles for territory and the contamination of our lands,” said Tzul Tzul.

For Eva Tecún, who is part of the Tz’ununija’ Indigenous Women’s Movement, the discourse of feminist organizing in Guatemala has changed, in large part because of the strength of Indigenous women’s organizing. But in practice, issues that are considered to be the domain of Indigenous women are still not given the attention they deserve.

“The political strategy of our movement is to elevate the demands of Indigenous women in different spaces of decision making and influence on the local, departmental, national and international level,” said Tecún. Many of the founders of Tz’ununija’ formed part of Communities of People in Resistance during Guatemala’s internal conflict, while others were involved in the peace process.

“Often, the struggle for collective rights is made invisible, and when women’s rights are talked about it is as individual rights,” said Tecún. Tz’ununija’ is made up of more than 80 active collectives of Indigenous women from Maya, Xinca and Garifuna communities around the country. Access to water, land, language rights and the allocation of local budgets to women’s organizations are key areas of collective struggle among the groups that make up Tz’ununija’.

“As Indigenous women raise their voices with their demands with regards to territory on March 8th, these demands still tend to be made invisible… by more global demands that are in the public agenda,” said Tecún. Though many Indigenous women participate in activities on March 8th, Tecún notes that September 5th, the International Day of Indigenous Women, is a key date in their calendar.

Against violence and institutions that protect aggressors

This year’s March 8th organizing took place as the issue of violence against women at the country’s largest public university began to boil over.

Over the course of an initiation ritual at the end of January, two young women were dumped unconscious in the grass outside of the architecture building on the campus of the University of San Carlos (USAC) in Guatemala City. Their parents were eventually called. When they took the two young women to hospital, the doctors mocked the still unresponsive women for partying too hard.

Days later, dozens of women from the USAC gathered to demand justice, and an end to the initiation rituals, which have long been criticized as violent and unnecessary. Following a short press conference, the women assembled lined up blindfolded and performed “A rapist in your path,” choreographed and written by Chilean feminists.

Murphy Paiz, the rector of the USAC, initially refused to respond to the concerns of students. Later, after a small group of congresspeople pushed him to testify, he said the initiations were a “tradition” and promised not to cancel them.

Outrage against the impunity granted to perpetrators led to the creation of a facebook page, where more and more women began to make anonymous complaints about abuse suffered at the hands of men.

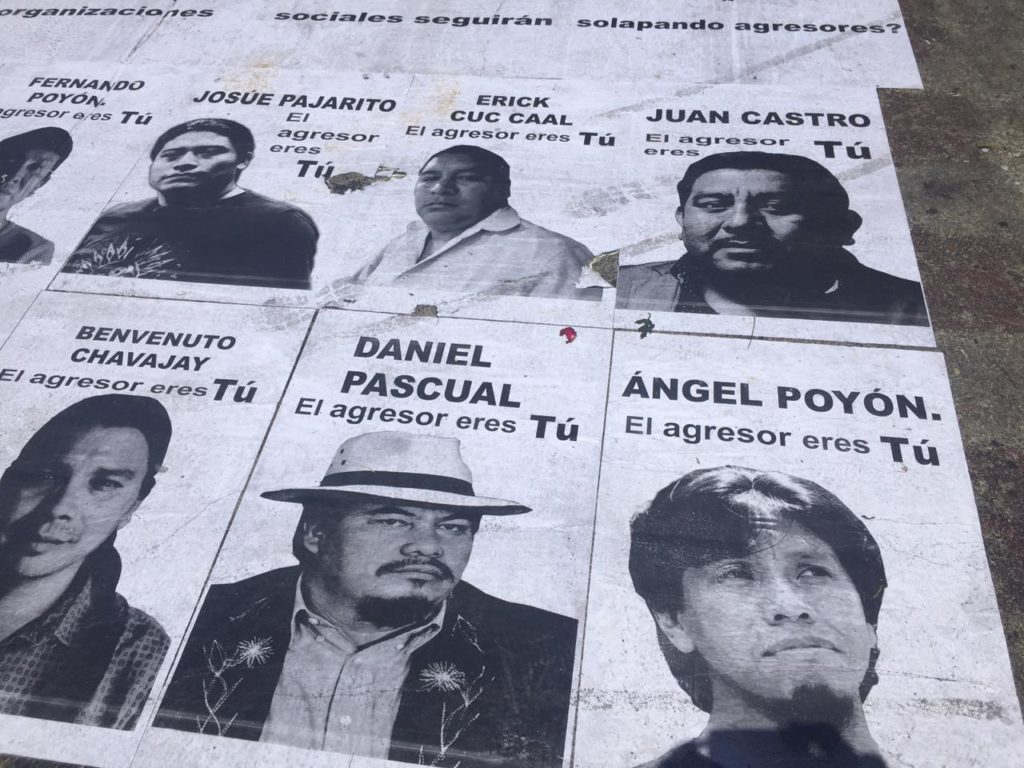

Soon, the complaints spread beyond students and accusations went up against politicians, public servants, and even men active in social movements and leftist organizations. Some of the men accused promised to open legal proceedings against the women who named them, or threatened to track them down individually.

The denunciations were controversial and have sparked divisions among organizations, including among women’s organizations.

This led to the creation of another campaign, “It was I, it was all of us,” in which women publicly voiced their support for those who had made the complaints. This strategy allowed individuals who made anonymous complaints to remain anonymous, while demonstrating they had solidarity and support.

“Many who had long kept quiet came out and said they wouldn’t be silent any longer,” said Tzul Tzul of the March 8th actions in Guatemala City.

Pandemic as political cover

The uproar around the abuse of women at the USAC began just after President Alejandro Giammattei took office on January 14th.

Since taking office, Giammattei’s government has moved forward with a series of evictions, in which communities (which are often but not always Indigenous) are physically removed from the lands where they live and farm, often without ensuring they have a safe place to go. Tzul Tzul, who has represented communities threatened with eviction in court, estimates there could be between 200-250 evictions pending on a national level.

By the third month in Giammattei’s administration, the novel coronavirus had reached Guatemala. According to Johns Hopkin’s University’s COVID-19 map, there are 2,265 confirmed cases in Guatemala, and 45 people have died. In early May, at least 117 of the coronavirus cases in Guatemala were among people recently deported from the United States.

Under a sweeping bill passed under the pretext of containing the spread of the virus, the Peace Secretariat and the Agrarian Affairs Secretariat were absorbed by a presidential commission. The Peace Secretariat was one of the few surviving government agencies tasked with materially implementing the Peace Accords signed between 1994 and 1996.

The new president has also pushed forward with reforms activists say would limit criticism and organizing against the government. He’s encouraged new legislation to classify street gangs as terrorist organizations, a move that could lead to the further criminalization of Indigenous resistance.

By all accounts, the pandemic response in Guatemala has led to further militarization. By mid-April, Guatemalan media were reporting that courts and prisons were swamped and that over 10,000 people had been detained for violating the stay-at-home order.

In San Pablo de La Laguna, Sololá, militarization under the pretext of containing the coronavirus has led to sexual violence, aggressions and harassment against Tz’utujil women. In a May 11 communiqué, Mujeres de Xib’alb’a and other organizations called de-militarization and demanded an investigation into the abuse, and protections for Tz’utujil women.

“As part of the civilian population, we can’t gather, or meet, we can’t organize together or carry out actions in defense of life, as communities do. We have to stay home,” said Tecún in a Zoom interview from her home in Chichicastenango. “This is a good scenario for mining companies.” Indeed, while ordinary Guatemalans have faced repressive penalties for carrying out their daily activities; mining, palm oil and other agribusiness activities have continued apace.

March 8 and the memory of state terror

The March 8th action in Guatemala City also recalled what happened in the morning hours three years earlier, when 41 girls were burned to death in a group home called Hogar Virgen de la Asunción (sometimes referred to as an hogar seguro, which translates as “safe home”), on the outskirts of Guatemala City.

Most of the youth at the shelter had been victims of sexual violence or human trafficking, and were supposedly under state protection. In the years leading up to the fire, local and national authorities were alerted hundreds of times regarding the inhumane conditions the children were facing.

On March 7, 2017, 52 girls and boys attempted to escape the facility. They were surrounded by approximately 100 heavily armed police and soldiers, who brought them back to the group home.

The 56 girls were locked into a small room together, spending the night without access to a washroom, to blankets and mattresses, or to food and water.

The next morning, a fire was started inside the room where the girls were trapped.

The supervisor of the shelter, with the “keys hanging from her belt,” stood and watched, as did more than a dozen police officers and other authorities. The fire spread, burning the girls as screams and smoke filled the building. The door wasn’t opened until most of the young women were dead: 41 of them died in the fire, on the way to the hospital or in hospital. Many of the 15 who survived are severely burned and suffer permanent organ damage.

“What we see and condemn is that there is a blanket of impunity that [the government] is trying to use to cover up the Hogar Virgen de Asunción case,” said Esteban Emanuel Celada Flores, a lawyer for Mujeres Transformando el Mundo, the group that is representing the victims in a lawsuit against the perpetrators.

“In this case, we see… to begin with, a strategy on the part of the prosecutor to minimize what happened, saying that there was culpable homicides, that there was bad treatment of minors, saying that there were minor injuries, none of that reflects the magnitude of the crimes committed against the victims,” he said. Some of the adults accused of supervising the massacre are in jail, many others remain free.

Celada Flores described how the hearings were held in the basement of the high rise where tribunals are held in Guatemala City, in which there was not enough space for media to be present. The case is currently on hold due to the pandemic.

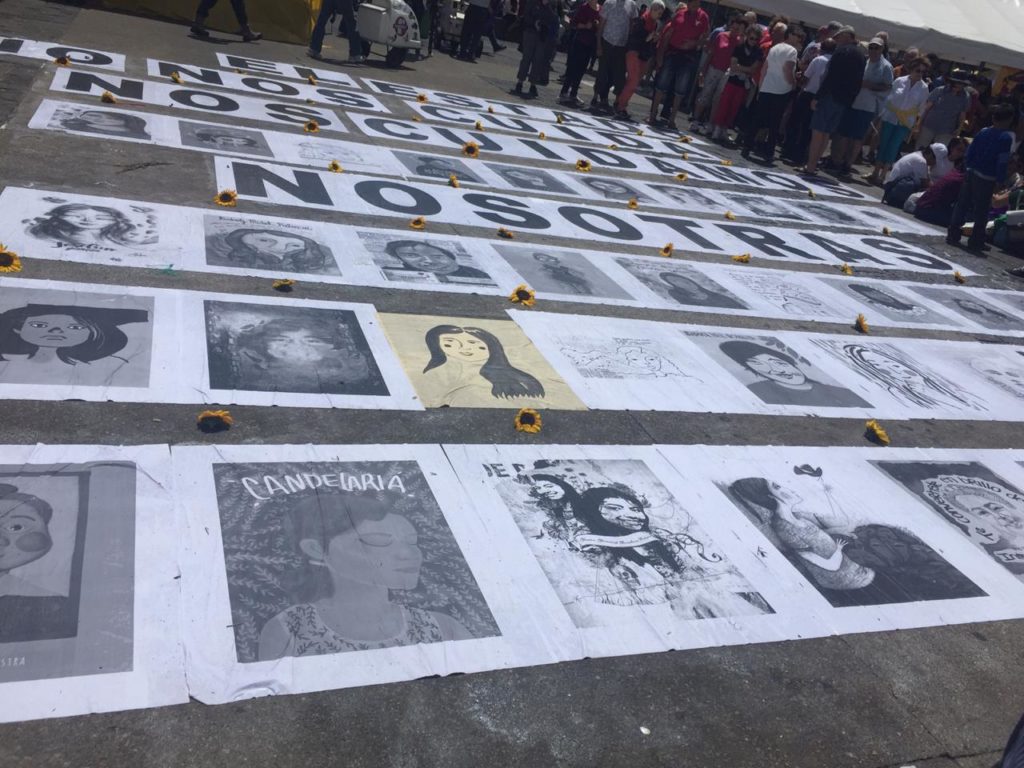

This year on International Women’s Day, 56 crosses were installed with the names of the young women locked inside the burning room at Hogar Virgen de la Asunción were installed in Guatemala’s Central Park.

Women who participated in the march carried sunflowers upon the request of the mothers of the victims of the Hogar Virgen de Asunción fire. The sunflowers represent the ability to turn toward the light in the darkness, and to grow closer together in order to survive.

This is the fourth report from Toward Freedom’s América Feminista series. Next week we’ll have a story on women’s organizing in Ecuador.

Author Bio:

Dawn Marie Paley is a journalist and editor of Toward Freedom. She’s the author of Drug War Capitalism. Follow her on Twitter @dawn_.