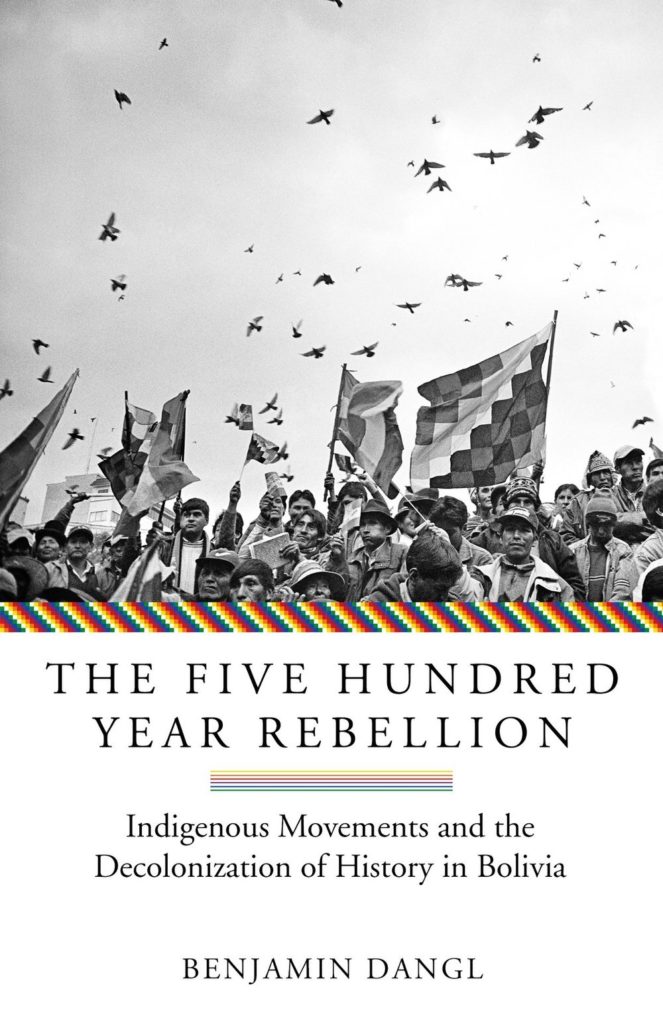

The following excerpt from my new book, The Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia, looks at the roots, rise and presidency of Evo Morales, who was overthrown in what is widely understood as a coup on November 10th. The book excerpt, written before this month of violence and state repression, describes how histories and symbols of indigenous resistance have been wielded as tools for liberation and political power in Bolivia, from the government palace to the street barricades.

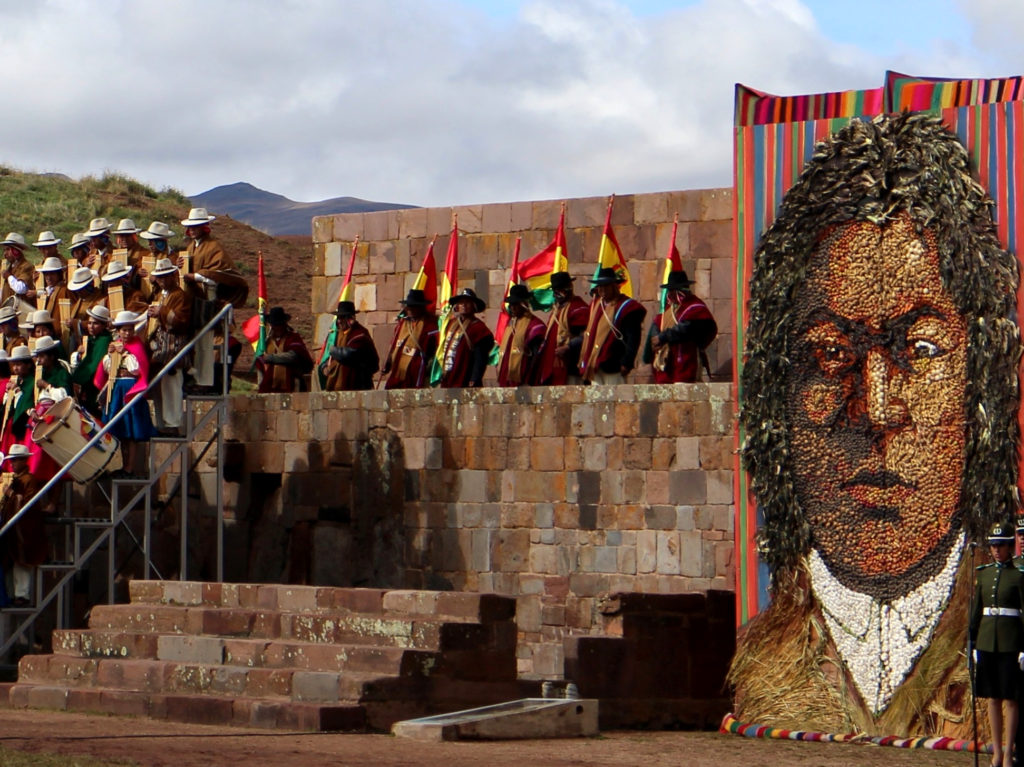

A caravan of buses, security vehicles, indigenous leaders, and backpackers with Che Guevara T-shirts wove their way down a muddy road through farmers’ fields to the precolonial city of Tiwanaku. Folk music played throughout the cool day of January 22, 2015, as indigenous priests conducted complex rituals to prepare Bolivia’s first indigenous president, Evo Morales, for a third term in office. His ceremonial inauguration in the ancient city’s ruins was marked by many layers of symbolic meaning.

“Today is a special day, a historic day reaffirming our identity,” Morales said in his speech, given in front of an elaborately carved stone doorway. “For more than five hundred years, we have suffered darkness, hatred, racism, discrimination, and individualism, ever since the strange [Spanish] men arrived, telling us that we had to modernize, that we had to civilize ourselves… But to modernize us, to civilize us, first they had to make the indigenous peoples of the world disappear.”

Morales had been reelected the previous October with more than 60 percent of the vote. His popularity was largely due to his Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party’s success in reducing poverty, empowering marginalized sectors of society, and using funds from state-run industries for hospitals, schools, and much-needed public works projects across Bolivia.

“I would like to tell you, sisters and brothers,” Morales continued, “especially those invited here internationally, what did they used to say? ‘The Indians, the indigenous people, are only for voting and not for governing.’ And now the indigenous people, the unions, we have all demonstrated that we also know how to govern better than them.”

For most of those in attendance, the event was a time to reflect on the economic and social progress enjoyed under the Morales administration and to recognize how far the country had come in overcoming five hundred years of subjugation of its indigenous majority since the conquest of the Americas.

“This event is very important for us, for the Aymara, Quechua, and Guaraní people,” Ismael Quispe Ticona, an indigenous leader from La Paz, told me. “[Evo Morales] is our brother who is in power now after more than five hundred years of slavery. Therefore, this ceremony has a lot of importance for us… We consider this a huge celebration.”

For critics on the political left, the Tiwanaku event embodied the contradictions of a president who championed indigenous rights at the same time that he silenced and undermined grassroots indigenous dissidents, and who spoke of respect for Mother Earth while deepening an extractive economy based on gas and mining industries. Indeed, the way the MAS used the ruins of Tiwanaku for political ends, as it had in past inaugurations, appeared shameful and opportunistic to some critics.

But such uses of historical symbols by Morales were part of a long political tradition in Bolivia. From campesino (rural worker) and indigenous movements in the 1970s to the MAS party today, indigenous activists and leftist politicians have claimed links with indigenous histories of oppression and resistance to legitimize their demands and guide their contested processes of decolonization.

When Evo Morales walked through the doors of Tiwanaku amid smoking incense and the prayers of Andean priests, for many Bolivians it was a profound moment marking the third term in office for the country’s first indigenous president. It was also just another day in a country where the politics of the present are steeped in the past.

The Morales government typically portrays itself as a political force that has realized the thwarted dreams of eighteenth-century indigenous rebel Túpac Katari, who organized an insurrection against the Spanish in an attempt to reassert indigenous rule in the Andes. This was underlined in the recent naming of Bolivia’s first satellite, Túpac Katari. The launching of the satellite was broadcast live in the central Plaza Murillo in La Paz, an event accompanied by Andean spiritual leaders who conducted rituals to honor Mother Earth. The government has also named state-owned planes after Katari. That Katari’s legacy could be put to use in such a way speaks to the enduring political capital of the indigenous leader.

Túpac Katari’s Symbolic Return

Over two hundred years before the Morales government launched a satellite bearing his name, the Aymara indigenous rebel Katari led a 109-day siege of La Paz that rattled Spanish colonial rule. Katari’s revolt was part of an indigenous insurrection across the Andes launched in 1780 from Cuzco and Potosí, and spread by Katari to La Paz in March 1781. A central demand of the revolts was that governance of the region be placed back into indigenous hands.

The Spanish eventually crushed the rebellion and captured Katari. It is widely understood that moments before his execution, Katari promised, “I will return as millions.” Indeed, though his dream of overthrowing the Spanish and gaining indigenous self-rule was crushed, during the hundreds of years that have passed since his execution, this martyr and his struggle have been taken up as symbols of indigenous resistance by countless movement participants, activist-scholars, and union leaders in Bolivia.

Activists have erected Katari statues, his name and portrait have graced placards and the titles of campesino unions, and his legacy has fueled dozens of indigenous ideologies, manifestos, and political parties. Katari’s street barricade strategies have been taken up again by twenty-first-century rebels, and the satellite named after him circles the globe.

Katari’s symbolism travels well. In April 2000, the specter of Katari returned in the form of a series of Aymara-led protests against water privatization and neoliberal policies. The protests involved road blockades that cut off La Paz from the rest of the country. Marxa Chávez, an Aymara sociologist with rural roots, became involved in the uprising. She told me that activists took turns maintaining the barricades and established vigils along the highways to signal when locals, visitors, and the military were arriving.

The very act of blockading roads to strangle La Paz recalled Katari’s struggle. “The blockade is a form of remembering the siege,” Chávez explained. The movement’s organization of road blockades utilized practical knowledge that had been “transmitted basically by oral memory.” For example, “there was a form of convening people in the Túpac Katari uprising which was to light bonfires in the hills so that other communities would see them, and it was a symbol of alert.” In the blockades of 2000, activists used the same style of fires to summon people. “That’s why hundreds of people later arrived in [the highland town of] Achacachi to face off with the military, because they had seen the smoke.” She placed the origins of the technique in the “unwritten memory in the communities.”

Three years later, another siege would rock La Paz, this time led by the same highland communities and spreading to El Alto. For weeks on end, Aymara activists maintained barricades surrounding La Paz to protest government repression and a plan to privatize and export Bolivian gas. The protests ousted the neoliberal president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and ushered in a new phase of grassroots organizing and leftist politics that paved the way for Morales’s election in 2005.

The Five Hundred Year Rebellion demonstrates how the grassroots production and mobilization of indigenous people’s history by activists in Bolivia was a crucial element for empowering, orienting, and legitimizing indigenous movements from 1970s post-revolutionary Bolivia to the uprisings of the 2000s and into today. For these activists, the past was an important tool used to motivate citizens to take action for social change, to develop new political projects and proposals, and to provide alternative models of governance, agricultural production, and social relationships. Their revival of historical events, personalities, and symbols in protests, manifestos, banners, oral histories, pamphlets, and street barricades helped set in motion a wave of indigenous movements and politics that is still rocking the country.

As contemporary Bolivian politics and movements demonstrate, the struggle to wield people’s histories as tools for indigenous liberation is far from over.

Coca Fields and Street Rebellions

The road to Evo Morales’s election was a long and tumultuous one, forged in coca fields and street rebellions. Morales is a former coca grower and union leader who rose up from the grassroots as an activist fighting against the US militarization of the tropical coca-growing region of the Chapare in the central part of the country. (Although it is a key ingredient in cocaine, the coca leaf is used legally for medicinal and cultural purposes in Bolivia.) Morales and other coca farmers saw the US-led drug war in the country as an attempt to undermine radical political movements, such as the coca unions Morales led. He became an early figurehead and dissident congressman in the MAS political party, which grew in part out of the coca unions and ran a nearly successful presidential bid by Morales against neoliberal president Sánchez de Lozada in 2002.

The MAS has always defined itself as a political instrument of the social movements from which it emerged. During the early 2000s, Bolivia saw numerous uprisings. In the 2000 Cochabamba Water War, the people of that city rose up against the privatization of their water by Bechtel, a multinational corporation. After weeks of protests, the company was kicked out of the city, and the water went back into public hands. In February 2003, police, students, public workers, and regular citizens across the country led an insurrection against an IMF-backed plan to cut wages and increase income taxes on a poverty-stricken population. The revolt forced the government and IMF to surrender to movement demands and to rescind the public wage and tax policies, ushering in a new period of unity and solidarity between movements as civil dissatisfaction gathered heat, reaching a boiling point during what came to be called the Gas War.

The Gas War, which took place in September and October 2003, was a national uprising that emerged among diverse sectors of society against a plan to sell Bolivian natural gas via Chile to the United States for eighteen cents per thousand cubic feet, only to be resold in the United States for approximately four dollars per thousand cubic feet. In a move that was all too familiar to citizens in a country famous for its cheap raw materials, the right-wing Sánchez de Lozada government worked with private companies to design a plan in which Chilean and US businesses would benefit more from Bolivia’s natural wealth than Bolivian citizens themselves would. Bolivians from across class and ethnic lines united in nationwide protests, strikes, and road blockades against the exportation plan. They demanded that the gas be nationalized and industrialized in Bolivia so that the profits from the industry could go to government development projects and social programs.

Neighborhood councils in the city of El Alto, many with ex- miners as members, banded together to block roads in their city. The height of the Gas War recalled Katari’s siege as it involved thousands of El Alto residents, organized largely through neighborhood councils, blocking off La Paz from the rest of the country and finally facing down the military. The government’s crackdown intensified as state forces in helicopters above shot the civilians below, leaving over sixty people dead. The repression pushed movements in the city into a fury that emboldened their resistance. By mid-October, the people successfully ousted Sánchez de Lozada and rejected the gas exportation plan, pointing the way toward nationalization.

The Evo Morales Government

Such protests and others promoting land reform and demanding a new, progressive constitution opened up new spaces for radical alternatives to the neocolonial state, putting Bolivian sovereignty and a full rejection of the neoliberal model at the center of the country’s politics. The MAS and Morales emerged from this period of discontent as the most adept at channeling the energy and demands of the grassroots while navigating the country’s national political landscape—one dominated at the time by right-wing political parties.

In 2005, Morales won the presidential election, largely thanks to the political space and popular hope inspired by social movement victories in the previous five years. Because he was the first indigenous president of Bolivia, his election was seen as a watershed moment in a nation where the majority was poor and indigenous. That Morales could be elected on a socialist, anti-imperialist platform after roughly twenty years of neoliberalism was historic. Perhaps even more significant was that, in a nation rife with racism and neocolonialism, an indigenous man from a humble background could take up residence in the presidential palace.

Shortly after assuming office, Morales moved quickly to institutionalize many of the social movement victories that had been won in the streets. He nationalized sectors of Bolivia’s rich gas industry, convened an assembly to rewrite the country’s constitution, and followed through on many of his campaign pledges to alleviate poverty and empower the poor and indigenous people living on the margins of society. His election notably took place at a time in Latin America when other progressive presidents were in power; from Argentina to Venezuela, Morales was not alone in asserting national sovereignty and rejecting imperialism.

The economic changes in the country point to some of the reasons Morales was so popular throughout much of his time in office. Bolivia’s GDP rose steadily from 2009 to 2013, contributing to what the UN called the highest rate of poverty reduction in the region, with a 32.2 percent drop between 2000 and 2012. The rates of employment and pay went up, buoyed by a 20 percent minimum wage increase. Much of this economic success can be tied to the government placing many industries and businesses—from mines to telephone companies—under state control, thus generating funds for the MAS government’s popular social programs, including projects seeking to lift mothers, children, and the elderly out of poverty. Thanks to a successful literacy program, UNESCO has declared the country free of illiteracy. Much of the funding created by nationalization also pays for infrastructure and highway development, as only 10 percent of the country’s roads are paved.

The MAS political project has not been without its pitfalls and structural problems. Some of the same indigenous and rural communities that the Morales government seeks to support with its social programs and politics have been displaced by extractive industries. Fields of GMO soy, accompanied by toxic pesticides, are expanding across rural areas in the eastern part of the country with the government’s support. Abortion is still largely illegal in Bolivia, and rates of domestic abuse against women and femicide have been on the rise. Major corruption scandals have beset the MAS and its movement allies, including the CSUTCB and the Bartolina Sisa movement. Morales is pushing forward with a controversial nuclear power plant to be built near earthquake-prone La Paz, and the MAS plans to build a highway through the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), a move which has sparked protests. (More recently, Morales has come under attack for policies that led to the wide-spread fires in the country.)

The contradictions inherent in the Morales administration’s decision to deepen extractivist projects in mining, gas, and mega-dams while simultaneously cheerleading Mother Earth will impact the nation and its indigenous movements for decades to come.

“The Open Veins of Latin America are Still Bleeding”

When I sat down in Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 2003 for an early morning interview with Evo Morales, then a coca farmer leader and congressman, he was drinking fresh-squeezed orange juice and ignoring the constant ringing of the landline phone at his union’s office. Just a few weeks before our meeting, a nationwide social movement demanded that Bolivia’s natural gas reserves be put under state control. How the wealth underground could benefit the poor majority aboveground was on everybody’s mind. As far as his political ambitions were concerned, Morales wanted natural resources to “construct a political instrument of liberation and unity for Latin America.” He was widely considered a popular contender for the presidency and was clear that the indigenous politics he sought to mobilize as a leader were tied to a vision of Bolivia recovering its natural wealth for national development. “We, the indigenous people, after five hundred years of resistance, are retaking power,” he said. “This retaking of power is oriented towards the recovery of our own riches, our own natural resources.” Two years later he was elected president.

Fast-forward to March 2014. It was a sunny Saturday morning in downtown La Paz, and street vendors were putting up their stalls for the day alongside a rock band that was organizing a small concert in a pedestrian walkway. I was meeting with Mama Nilda Rojas, a leader of the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu, an indigenous organization then facing repression from the MAS for its critiques of government policy. Rojas, along with her colleagues and family, had been persecuted by the Morales government in part for her activism against mining and other extractive industries.

“The indigenous territories are in resistance,” she said, “because the open veins of Latin America are still bleeding, still covering the earth with blood. This blood is being taken away by all the extractive industries.” While Morales saw the wealth underground as a tool for liberation, Rojas saw the president as someone who was pressing forward with extractive industries without concern for the environmental destruction and displacement of rural indigenous communities they left in their wake. “This government has given a false discourse on an international level, defending Pachamama, defending Mother Earth,” Rojas explained, while the reality in Bolivia is quite a different story: “Mother Earth is tired.”

Critiques of the MAS and Morales are rampant among Bolivia’s dissident indigenous movements and thinkers.

“I had so much hope at the moment when Evo Morales came into the government,” Bolivian sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui explained. “But he has come to crave centralized power, which has become a part of Bolivia’s dominant culture since the 1952 revolution. The idea that Bolivia is a weak state and needs to be a strong state—this is such a recurrent idea, and it is becoming the self-suicide of revolution. Because the revolution is what the people do—and what the people do is decentralized.” She continued, “I would say that the strength of Bolivia is not the state but the people.”

The Power of the Past

While Bolivia’s diverse social and indigenous movements wield power from the streets, the MAS and Morales have successfully maintained and deepened their influence in part by mobilizing indigenous and working-class identity as an extension of party politics. The coca leaf is often used by the MAS in political campaigning as a symbol both of indigenous history and of the fight against US imperialism. Similarly, the government’s championing of indigenous culture more broadly, and its connecting that culture to a nationalist project of liberation and development, resonates with many voters who felt they had been manipulated by previous political leaders who, rather than seeking to decolonize and refound the nation on the basis of its indigenous roots, instead wanted to turn Bolivia into a mirror image of the West.

Many of the same histories, discourses of indigenous resistance, and symbols of revolt produced and promoted from below by indigenous movements over the period examined here are now celebrated as part of official state policy and rhetoric under Morales. The administration has made the wiphala part of the official national flag, granted new rights and power to indigenous communities, named a satellite after Katari, and published new editions of the works of indigenous philosopher Fausto Reinaga and other formerly dissident thinkers and historians.

Some of these government approaches have popularized images of Katari more as a distinguished head of state—to suit Morales’s position—than as a rebel leader. Katari has been portrayed in a number of ways throughout Bolivian history: during the MNR revolutionary period he was sometimes depicted in paintings holding a gun, and the Kataristas saw him as a defiant, chain-breaking symbol of their struggle.

During its first months in office, the MAS government chose another version that represented Katari as a stately leader, not a revolutionary. This version of Katari was requested in 2005 by former president Carlos Mesa, not Morales. In the portrait, scholars Vincent Nicolas and Pablo Quisbert explain, “Katari is no longer represented as a rebel, but as a dignitary of the State, dressed in a kind of jacket and a modern shirt, covered in an elegant poncho adorned with textile figures, and grasping a special staff of authority, a symbol of his power.” Though produced before Morales’s election, this image was taken up by his administration and widely distributed to tie Morales to Katari. “The Evo-Katari affiliation,” Nicolas and Quisbert write, “has been supported very much in this iconography, and is placed as a kind of backdrop to Morales himself.”

Such political uses of the past and historical symbols can be traced in part to the government’s Vice Ministry of Decolonization, which was created in 2009 and works with other sectors of government to promote, for example, indigenous language education, gender parity in government, indigenous forms of justice, antiracism initiatives, indigenous autonomy, and the strengthening of indigenous traditions, symbols, and histories.

One of the people involved in such decolonization efforts in the vice ministry was Elisa Vega Sillo, a former leader in the Bartolina Sisa movement and a member of the Kallawaya indigenous nation. She told me of the process of decolonizing indigenous history in Bolivia.

“We try and recover an anticolonial vision above all,” she said, focusing on how indigenous people, over centuries of resistance, “rebelled to get rid of oppression, the slavery in the haciendas, the taking over of land, of our wealth in Cerro Rico in Potosí, our trees, our knowledge—they rebelled against all of this. But in the official history, the colonial history, they tell us that the bad ones were the indigenous people, and that they deserved what they got.” She explained, “We recuperate our own history, a history of how we were in constant rebellion and how they were never able to subdue us.”

As a part of these efforts, government-led rituals now take place every November 14 to mark the death of Túpac Katari. Yet, sociologist Pablo Mamani asks, why remember Katari only every November 14, as though he is dead? “We must put this kind of ritual behind us to enter a more everyday rituality,” he explains. Mamani sees no need to remember Katari just one day a year, because “Túpac Katari has returned and is among us, and we, ourselves, are the thousands of men and women that we have in these territories, and we are on our feet, walking.”

Author Bio

Benjamin Dangl has a PhD in Latin American history and has worked as a journalist throughout Latin America for over fifteen years. He is a Lecturer in Public Communication at the University of Vermont and is the author of the booksThe Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia, Dancing with Dynamite: Social Movements and States in Latin America, and The Price of Fire: Resource Wars and Social Movements in Bolivia. Website: BenDangl.com.