As the world’s largest economies struggle to reign in the spread of the coronavirus, uncertainty remains about the manifold impacts the pandemic is having in southern Africa. There, like elsewhere, the fight against COVID-19 is in its early stages.

“The worst is yet ahead of us,” cautioned World Health Organization director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus late in April. Soon after, the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa offered this dire warning: “between 300,000 and 3.3 million African people could lose their lives as a direct result of COVID-19, depending on the intervention measures taken to stop the spread.”

So far, the virus has been slow to reach the continent. As of May 3 the Africa Center For Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) confirmed 44,873 cases and 1,807 deaths. South Africa has borne the brunt of the outbreak, while West and Central Africa are of growing concern.

These numbers could be underreported because –like the rest of the globe– African countries lack testing capacity. But to date, the numbers in Africa are still far, far less than what the US has suffered, at a time when China’s economic partnership with Africa has never been greater.

WHO Regional Director for Africa Dr. Matshidiso Rebecca Moeti, said during a March 19th press conference they initially wondered if the continent’s heat and humidity may be helping, but in no way would she confirm this.

Could it be something else?

Having dealt with the Ebola virus twice during the previous decade may shield some African nations from a COVID-19 surge.

Dr. Moeti said many labs remain in place from the Ebola crisis of 2014, which most affected Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Nigeria. Ebola struck again 2018-2019 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

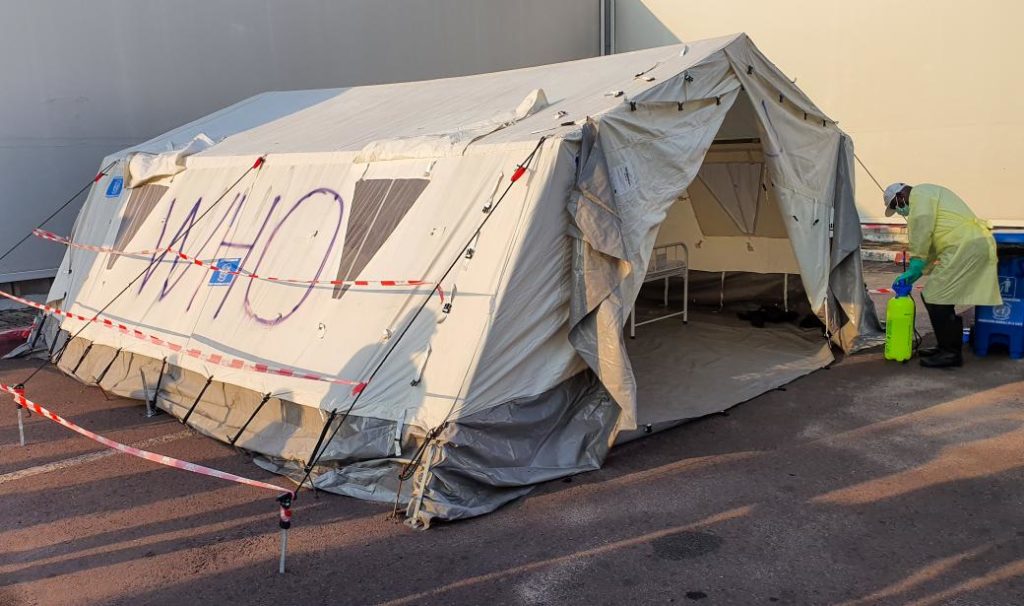

During the most recent outbreak, WHO Africa responded by creating “response pillars” within countries surrounding the DRC. These include temperature checks at points-of-entry (airports), decontamination teams, and contact tracing, arguably the most challenging response pillar.

This Ebola infrastructure and experience has shifted towards COVID-19, said WHO Africa technical officer Dr. Mary Smith in an interview from her office in Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of the Congo.

“Because we have the capacities in place to deal with the Ebola, we are able to respond to the COVID disease. It’s just a matter of adjusting to the particularities of this new disease,” she said.

This Ebola wisdom is not widespread across the continent though, says W. Gyude Moore, senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington and Liberia’s former Minister of Public Works (2014-2018).

What is more worrying are Africa’s fragile health systems, according to Moore.

“Even in those places where the lessons were learned, their health systems remain really, really weak and almost dangerously dependent on outside support to survive,” he said in a phone interview with Toward Freedom. “Most of those countries also have large numbers of people living with HIV-AIDS, and Africa also carries the brunt of the malaria disease burden. You have health systems that struggle to provide service and care to known infectious diseases.”

Dr. Smith was part of an Ebola contact tracing team in Nigeria in 2014. If an individual at a point of entry showed symptoms for Ebola, they were made to go into isolation for 21 days. For COVID-19, it’s 14 days, she says.

Teams then used geo-coordination through cell phones to pinpoint where the infected were and whether they remained isolated. Dr. Smith said if COVID-19 results in “more contacts, we just need more people.” She’s confident WHO Africa can muster the personnel to do what sounds like the impossible.

“There’s nothing impossible about it. It is possible and doable. We did it for the Ebola virus,” said Dr. Smith. After an infected person recovered, case management teams were dispatched to decontaminate the house where they lived, she adds.

Even so, as potential disaster stares them square in the face, some African governments may have sabotaged any advantages they have against the virus.

Early in April, the Washington-based nonprofit Friends of the Congo sent a video to this reporter which showed a large crowd clamoring to buy “quarantine passes” in Kinshasa, the DRC’s capital, with an estimated population of 15 million.

On April 2, Kinshasa’s local government decided to quarantine the affluent and diplomatic enclave within downtown known as Gombe. Residents began fleeing in order to avoid lockdown.

The local government then put a further restriction on the Gombe quarantine –anyone wanting to enter or leave the area had to pay around $20, according to Kambale Musavuli, the spokesperson for the Friends of the Congo.

“This video illustrates the real difficulty Congo has when its leaders are motivated by profit and not people’s interests. But this situation was predictable,” Musavuli told Toward Freedom.

He says it’s too early to tell whether WHO Africa and others have made a difference against the virus in the DRC. Yet as of April 22nd the virus has claimed 25 lives and infected roughly 350, according to WHO Africa.

For more than two decades Musavuli has watched his native DRC grapple with state corruption, civil war, and the West’s insatiable appetite for DRC’s natural resources. The DRC is one of the world’s poorest nations, at the same time as it is the world’s biggest producer of cobalt and tantalum, both of which are vital for manufacturing cell phones.

When considering how many artisanal miners there are, and how many in the DRC live day-to-day, Musavuli says mimicking the West’s stay-at-home orders could backfire. In late April, the International Monetary Fund said the DRC’s economic situation was “deteriorating quickly” and responded with a $363 million loan.

“The reality of the Congo is, you cannot do a lockdown, make everybody stay home,” he says. “If they don’t leave the house, they can’t feed themselves. So we know we need a different way.”

During the March WHO Africa press conference, Dr. Moeti suggested the virus may surge when winter comes to the continent– Africa’s winter season occurs over June, July, and August.

Moore says Africa’s low numbers so far could be attributed to its Ebola experience, but it is probably a constellation of factors. The continent’s population is relatively isolated, has the largest concentration of young people in the world (according to the UN), and many countries acted quickly with lock downs. In addition, many Africans self-medicate with herbal remedies and many others won’t seek hospitalization.

One significant factor which could derail Africa’s effort to stave off a surge of infections is its level of testing. Like the US and some European nations, many African nations are scrambling for necessary testing kits.

The Africa CDC said there is a large gap in testing rates between nations as much of the rest of the world imposes “restrictions on exports of medical materials.”

“…The collapse of global co-operation and a failure of international solidarity has shoved Africa out of the diagnostics market,” Africa CDC’s John Nkengasong told the BBC on May 4th.

“If a larger, larger number of people have respiratory problems we will see that in hospitals, but we are not seeing that in hospitals yet,” according to former Minister Moore. “It could be a contribution of all these things.”

As the continent prepares and waits for the virus to run its course, Moore and others are hoping Africa’s recent histories with equally hellish diseases will protect the continent from the worst.

“It’s really, really too early to know what exactly is happening in Africa,” he said.

Author Bio:

John Lasker is a freelance journalist from Columbus, Ohio. In 2013, with help from Toward Freedom, he won a Project Censored award for his work regarding military sexual trauma and the non-combat deaths of women soldiers in the US military.