On September 7, 2017 the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region of Oaxaca shook with an 8.2 magnitude earthquake, the second largest earthquake in Mexico’s history. In Juchitán de Zaragoza, which lies less than 100km from the epicenter, the impact was devastating.

The earthquake, and subsequent aftershocks, resulted in 65 deaths, 37 of which occurred in Juchitán. About half of the municipality’s 14,000 buildings suffered severe structural damage. Much of what took place following the earthquake in Juchitán was overshadowed by another earthquake twelve days later, which killed over 300 people in Mexico City. Even so, the ongoing consequences of earthquakes near Juchitán continue, and are entangled with the impacts of mega-projects in the region.

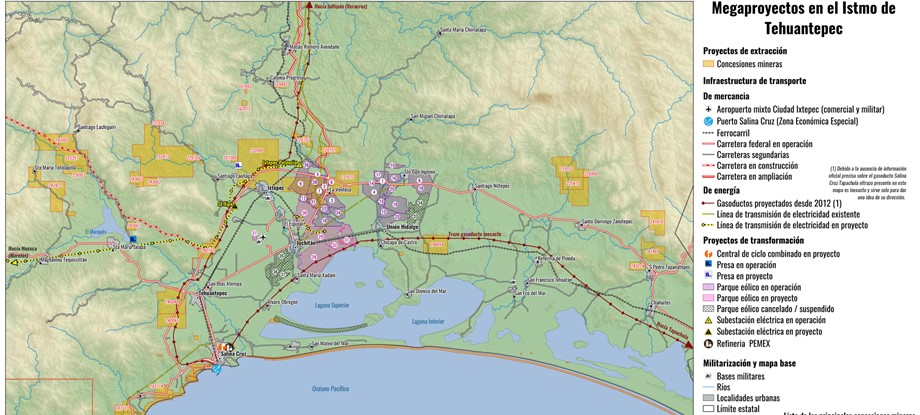

Since 2011, the Isthmus has been engulfed in struggles over large-scale wind parks, which in 2016 escalated when the region was declared a Special Economic Zone (SEZ). The SEZ, which provides incentives for foreign direct investment, was technically cancelled on April 25, 2019 by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). It was soon replaced with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Integral Development Program (PDIIT), managed by the same bureaucrat in charge of the SEZ. The PDIIT has emerged alongside Tren Maya—a proposed train across the Yucatán peninsula—that critics say is meant to create “a border wall without bricks.”

Zapotec Land defenders believe the PDIIT is a rebranding of the SEZ, which will follow the same trajectory of development via megaproject. “The Isthmus Interoceanic Corridor is the complete industrialization of the landscapes that is my home,” explains Mariana Solorzan, a Zapotec activist who has been involved in multiple struggles in the region.

Solorzan says PDIIT represents “the industrialization of our lives, the reproduction of a [development] formula that is failing everywhere and is a train heading to a dead end pit where we will drown.” It will increase mining and other infrastructure like pipelines, highways, trains and wind parks.

The earthquakes interrupted this infrastructural conflict, disrupting the construction of proposed wind energy projects planned around Unión Hidalgo and the Laguna Superior, each about a twenty-five minute drive from Juchitán.

As a researcher who has worked in these areas since January 2015, it is clear that the earthquakes underscored the importance of natural Zapotec buildings and design as a key mechanism of community wellness. But that story cannot be told without looking at how wind farms in the region are often in direct conflict with traditional building styles.

The Earthquake & Infrastructural Resilience

While the impact of the earthquakes were severe, some towns and homes were impacted less than others. Juchitán, as mentioned, was devastated, but residents of surrounding towns—many of which are fighting wind park development—were less affected.

Maria Xochimeh, a resident of Gui’Xhi’ Ro (Álvaro Obregón), said that in their community, “not a single house fell to the ground.” While some houses experienced structural damage, many did not because their kitchens “were made of palm” and they were “not a part of the concrete house—it’s not all bunched together.” The more traditional and dispersed courtyard layout, with trees and plants used for daily life, also helped absorb the impact and reduce damage to homes.

This was not the experience in San Blas Atempa, Tehuantepec, Juchitán, Matias Romero and the other main towns devastated by the earthquake. This has to do with the reduction of courtyard space due to dense urbanization, the proliferation of concrete houses and faulty material and construction regulations. Soil moisture, which can mitigate earthquake shocks, is another factor.

Humanitarian aid slowly arrived in the isthmus following the earthquake. Aid materials were the usual tents, tarps, ropes and food provisions. Land defenders I interviewed told me how they watched plastic and trash proliferate across Juchitán during recovery efforts. This was matched with sadness. Carlos Martínez, a Zapotec activist, witnessed a “terrible loss of historical memory about using palm to make rooftops and the general vernacular architecture” as people scrambled to access tarps.

In the early morning hours of October 26, 2017, “the wind blew at 216 kilometers an hour and it began ripping of the tarps and ropes from the majority of the camps,” according to Martínez. The Isthmus has some of the best wind resources in the world, hence the location of wind parks in the region. “The majority of the tents were destroyed around three in the morning,” explained Martínez, “but the families who raised their camps with the traditional palm and reed thatch roof (enramada) whose camps were just shaken by the winds without sustaining any real structural damage.”

An “enramada can last up to eight or ten years without needing any repairs at all, but a tarp will not last so many years –it will last three years maximum before the sun and the salt wear them out,” said Martínez.

Wind Parks and Cultural Strangulation

As the 2017 earthquakes brought the power of Zapotec natural building to the fore, wind park development continues to conflict with this ancient architectural style. Despite active community resistance since 2011, the Isthmus has been subject to the construction of over 2,000 wind turbines. While resistance in the coastal region had succeeded in stopping wind park construction on the Santa Teresa sandbar and the Pacific Ocean, wind projects are still proposed and being erected throughout region.

Referring to an area “where palm grows wild for roof tops” in Union Hidalgo, Zapotec land defender José Arenas explains how since the DEMEX wind park opened in 2012, the process of palm leaf regeneration has become increasingly slower. Farmers in the region contend that due to the reduction of underground water, whose flow has been drained by the wind turbines, palm and other crops have suffered.

Ground water resources in the Isthmus are traditionally 3-9 feet beneath the ground. Among the major impacts of the wind turbines is soil compaction from road expansion, in addition to the construction of wind turbine foundations that range between 32-45 feet deep and 52-68 feet in diameter. Soil compaction and the pouring of steel reinforced concrete into the ground has caused serious hydrological and soil changes in the region, affecting what remains of smallholder farming and preventing fresh water from draining into the Laguna Superior, which can raise the salinity levels.

The privatization of communal land has also impacted access to traditional building materials. Efforts to privatize and grab the 68,112 hectares of communal land by private industry around Juchitán have been persistent and taken to another level with new wind resource valuation. This has affected how locals respond to earthquakes.

“Even though we know traditional modern palm houses are better against earthquakes, we cannot just go and get the raw material anymore because the two wind companies set up the wind park industrial zones where we use to gather those resources,” explained Mariano López Gómez, another Zapotec land defender. “The few remaining trees left are not accessible anymore because the companies have land-leasing contracts that prevent people from building mud and palm houses.”

The pattern of exclusion that stifles subsistence and traditional building practices continues with proposed wind parks. Currently, Electricity of France (EDF) is trying to build a new wind farm called Gunaa Sicarú (Beautiful Woman, in Zapotec) a 252MW facility with 96 wind turbines. While there are extensive issues related to the granting of permits, as well as the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) consultations and violent intimidation, the wind farm will also substantially degrade palm resources use in the region.

“The Zina palm is endangered by the construction of the [EDF] wind park that will require the destruction of 5,000 hectares of palm trees near Union Hidalgo,” explained Carlos Martínez, the Zapotec activist, in an interview.

Not only are there severe hydrological and soil impacts, but wind parks require habitat and tree clearance around roads and high-tension wires. The wind turbine construction site eliminates the possibility of self-sufficient and traditional construction. Martínez wants “to promote the information about the Zina palm forest so it can be protected and we can continue living with it.” The value of palm trees and the negative impacts of wind park development on them remains under acknowledged.

The value of traditional construction and palm resources must be recognized, developed and celebrated. The culture of plastic and energy intensive infrastructure development paves over and exclude autonomous solutions to the “social disasters” trigged by earthquakes.

Supporting cultural development and honoring traditional construction can challenge the costly, plastic centric supply chains wedded to humanitarian aid. As Martínez stressed: “it is very important that we maintain this construction knowledge, and take care of palm trees and reed.”

Traditional Zapotec building and the synchronization of development and humanitarian aid with local knowledges and resources should prioritized. This would lead to the promotion of cultural revitalization and self-sufficiency and stop the spread of wasteful production processes and products.

Author Bio:

Alexander Dunlap is a post-doctoral researcher fellow at the Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM), University of Oslo. Find him on twitter at @DrX_ADunlap.