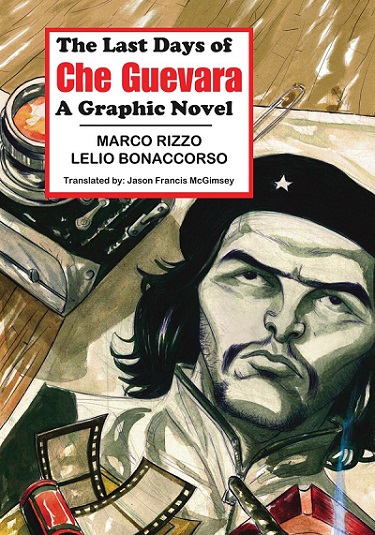

Reviewed: The Last Days of Che Guevara: A Graphic Novel. By Marco Rizzo and Lelio Bonaccorso. Translated by Jason Francis McGimsey. Toronto: Red Quill Books, 124pp, $18.00

No iconic, rebellious image of anyone from the 1960s, it is safe to say, looms larger than that of Che Guevara, even today, so long past his death. Only Bob Marley’s face will be seen on nearly as many t-shirts around the planet, but signifying a different set of rebellions, despite the intriguingly close vicinity of Cuba and Jamaica. Che is the one in museums, and on towels in Italy, posters in Vietnam, statues and assorted monuments in Venezuela and so on. The photo by “Korda” (erstwhile fashion photographer Alberto Diaz Gutierrez) bears a ghostly reminder of the great romance of revolution, what was attempted and what was lost.

The Last Days of Che Guevara is a highly curious graphic nonfiction “novel” not easily categorized as comic art in the usual sense. It combines several chapters narrating the incidents of the title, an Epilogue with a dozen pages of color sketches the themes, a factual chronology and an expanded “acknowledgment” that details liberties taken by scriptwriter and artist with known facts of the notorious assassination.

Add to this some oddities and some notable absences from the book. At least several other graphic nonfiction novels about Guevara’s life have appeared (reviewer’s disclosure: I edited one of them, Che by the late, great Spain Rodriguez, with a half-dozen global editions), but only the mainstream commercial version seems to have made no impression on the collaborators, even to the degree of acknowledgments. Likewise, the scholarly literature cited on the subject is fairly dense, but a highly prominent, arguably definitive work by leading civil liberties lawyers Michael Ratner and Michael S Smith, The Assassination of Che Guevara, is absent from the Bibliography, perhaps not known about because it appeared only as an ebook.

And yet The Last Days of Che Guevara a fascinating and impressive book in several ways. Its Expressionist motif may not be to the taste of many art-comic readers but the powerful narrative and drawing styles stand out. “Styles” in the plural, that is, because even within the main section of the book, the format shifts from mostly art pages to others heavy with prose, and then beyond the color pages to a section of personality portraits with a paragraph of explanation for each one. Reading this book, then, is a bit like being in one of the comic-art galleries of today in which each room is a surprise, related to, but distinctly unlike, the previous room.

Scriptwriter Marco Rizzo says in the volume’s last pages that the book is unique, after all, in the artistically recounted story of a photograph, i.e., the famous Korda photo. (Perhaps it is not too much to note here that the Afterword to Rodriguez’s Che, written by Sarah Seidman and myself, examines the iconography of Che Guevara generally.) Each of the seven pages in this mini-section bears a single drawing, with a text below: not much like comics, more in the “illustration” category. The thirteen previous pages, in color, recount the murder and the response of radical youngsters across borders and continents. The continuity of these two sections with the earlier parts of the book seems uncertain or perhaps meant to be artistically ambiguous. Each element of the book offers its own statement, its own testament.

In the end, I put the Spain Rodriguez version next to this one, leaving aside a curious manga version of Che’s life and the still more predictable comics “pro” or mainstream account by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon. Spain and the Italian artists think of themselves as radicals or revolutionaries, and they seek to continue Che’s life in ways beyond his physical presence. They are heavy on martyrdom, The Last Days in particular, for obvious reasons. And they are heavy on the inner life of Che himself, his commitments, his personal courage (he reputedly said to his executioner, “Shoot, coward. You are only killing a man!”) and the weight of his death upon ourselves. The suffering of ordinary people under the boot heel of the rich, a suffering that struck him early, as a physician, has not yet been redeemed. But perhaps the presentation of his life in different ways will still make a contribution to that redemption.

Paul Buhle’s most recent comic is Bohemians, reviewed in these pages. His next comic is a life of Rosa Luxemburg.