by Charlotte Dennett

Robert Fisk’s death on October 30th came as a profound shock to journalists around the world, especially those who knew him. And, in a deeply personal way, it was devastating to me as well, though I never met him. I will try to explain what his truth-seeking meant to me, as a former reporter in Beirut and as someone who has shared his anguish over the horrific death and destruction that has engulfed the Middle East.

Regrettably, the first time I missed meeting him happened some four decades ago. He arrived in Beirut in 1976, a year after I l left as a refugee of the Lebanese civil war. He carried on, bravely covering that 15 year old war as well as the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen. He seemed possessed to tell the world what the mainstream media was not reporting about the Middle East, which (I told my future husband after returning to the States), was the most censored part of the world. I would later explain why this was so while investigating the death of my father, America’s first master spy in the Middle East; in telling my own story, I would often seek out Fisk’s reportage in The Independent for insights and reliable information.

The second missed meeting happened after I watched, on October 28th, the 2019 documentary on his life by Yung Chang called This is Not a Movie: Robert Fisk and the Politics of Truth. It so moved me that I vowed to get ahold of him immediately. Alas, I missed him again. He died two days later. Sometimes, life is unfair. So, obviously, is unexpected death.

He apparently died of a severe stroke at age 74. His death comes at a time when journalism is under siege as “fake news” and in a world that needs the truth more than ever. But his loss is even greater for anyone who wants to understand what is really happening in the Middle East.

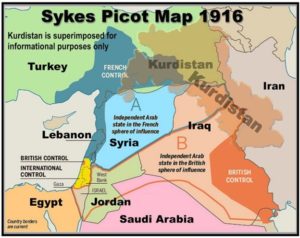

In the film, Fisk explains how as as boy he was greatly influenced by his father, who loved history and shared with his son his experiences in two world wars, with many trips to the battlesights. Fisk would go on to discover that the mysteries of the Middle East conflict could be unlocked by first studying the infamous Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916, which secretly carved up the former Ottoman Empire after World War I for French and British plunder . Since then, the journalist/historian avers, no place on earth has suffered more than the Middle East. “The history of the Middle East,” he tells us, “is a history of war.”

In his reporting, he consistently sought out those whose lives had been severely affected by the endless wars in the region, having concluded that the role of the reporter was to “be on the side of those who suffered.” This ethos competed sharply with journalism schools that taught that a reporter had to be objective and present both sides of an argument. Fisk’s famous retort: “If we were reporting the slave trade in the 18th century, would we give equal time to the slave ship captain?” His honesty earned him many enemies, but also gained him enormous respect among his colleagues. In fact, Fisk received more awards for his journalism than any journalist alive.

The New York Times described him as being a “dauntless journalist” who was “widely praised by colleagues and competitors alike for relentlessly chronicling the Middle East’s many agonies.” But the obituary, no doubt in the interest of balanced reporting, went on to add he “was also faulted by some critics as insufficiently tough at times on despots.”(This could be a reference to his reportage on Syria and its leader, Bashir al-Assad, of which I have more to say below.)

The Washington Post called him a “daring but controversial British war correspondent.” Like most obituaries on Fisk, the Post’s remembrance made reference to his three interviews with Osama bin Laden in the 1990s, a feat which distinguished him from other reporters but made him controversial, especially after 9/11. The Post noted that “Mr. Fisk condemned the mass killings orchestrated by bin Laden while focusing his journalism on the motives of the attackers and the failures of U.S. intelligence. To some, that smacked of sympathy for the terrorists, leading to a deluge of hate mail.”

The motives of the attackers. That’s an area where most foreign correspondents in the Middle East dared not tread, at least when I was there. If you watch the film, you come to appreciate how the battles Fisk covered shaped his views and his determination to dig deep into the causes of the wars he witnessed first hand.

What does the documentary tell us?

The film opens with his covering the later stages of the Iraq-Iran war, which began in 1980 and dragged on until 1988. We see him dodging bullets in Iraq near the Shatt al Arab River that separates Iraq from Iran. With his trusty notebook in hand (“notebooks are not obsolete,” he reminds us), he heads toward billows of black smoke rising from the burning oil storage tanks in Iran’s oil port of Abadan. The scene is perhaps a subtle suggestion that wars in the Middle East have often been fought over oil.

Much of the footage covers his chronicling the war in Syria, which is reportedly the subject of his new book, hopefully to be published posthumously. (He had already written 900 pages according to one of his last interviews). A particularly haunting scene finds him trekking through the ruined streets of Homs, surrounded on all sides by the huge, shelled out carcasses of buildings which once housed people.

“The dead can’t talk and the living are gone,” he laments. “Where did they go?” And where, the viewer wonders, were the other reporters?

In another segment, we find him in the Syrian city of Idlib having heard that massive fighting was about to occur. Idlib, he explains, is “the last stronghold of ISIS and a great humanitarian catastrophe,” its residents caught between fierce battles carried out by islamist jihadists and Syrian forces. He tells us that it is impossible to travel into ISIS-held territory, but even if journalists were free to go there, they wouldn’t want to go because “if you go too close, you might end up dead.” He admits his reporting on Syria was one sided for this reason, but avows the importance of a journalist going “to whatever scene you can get to, because if you don’t get to the scene, you can’t know the truth.” The truth in Idlib was that Fisk found no evidence of large-scale fighting at the time, as other news reports filed by “hotel journalists” were claiming. Again, there were no signs of other reporters in the town.

In keeping with his credo to go to the scene, he traveled to the heavily bombed Syrian town of Douma near Aleppo, site of an alleged chemical attack in 2017, which had NATO countries blaming the Assad regime and clamoring for intervention.Fisk, for his part, was determined to get to the truth by talking to residents and asking them for evidence of chemical weapons. He could find no witnesses to the attacks, but did learn that many fell sick by breathing in the dust created by successive bombings.

.

In the course of his rummaging in the rubble of Douma, he found a document that showed that arms used in the region had been supplied by Czechoslovakia. How did they get to Syria? he wondered. He traveled all the way to the arms manufacturer in Bosnia to find out, and learned that the weapons had been legally sent to Saudi Arabia. NATO, he added, hadn’t bothered to track the weapons to their final destination. The implication: Saudi Arabia was supporting the fighters against the Assad regime. (And my own research into the matter confirms this.) By the end of the film, we learn that members of the Organisation for the Prevention of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) had been pressured to suppress a dissenting 15 page report that found “no evidence” of the chemical attacks being dropped from the air by Syrian helicopters, as the official report alleged to the contrary.

I was reminded of a passage in my book about Fisk’s prescription for good journalism, that is, to “challenge authority, all authority, especially so when governments and politicians take us to war.” He had written disdainfully of President Bush’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, his articles drawing such impassioned responses that a new word entered the English lexicon: “fisking.” The Cambridge Dictionary describes fisking this way: “the act of making an argument seem wrong or stupid by showing the mistakes in each of its points, or an instance of doing this: It was the best fisking I’d read in a long time.” A synonym, the dictionary added, is “suspecting and questioning.” In February, 2003 Fisk’s “Case Against War” in the Independent took apart all the U.S. and British rationales for the war.

The Tragedies of Lebanon

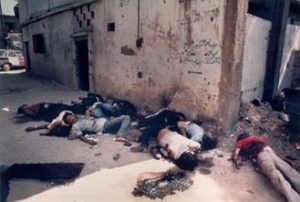

Lebanon was Fisk’s home base, so it would come as no surprise that he personally visited the scene of the horrific 1982 slaughter of 1200 Palestinian men, women and children in Beirut’s refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. In the film he describes stepping over bodies, confessing he had never seen so many dead people. “Massacres are difficult to forget if you see corpses,” he says. He admitted to being profoundly affected by the scene.

He came away feeling that “those people would want me to be here,” to tell the truth of what happened, namely that Lebanese right wing militia goaded on by nearby Israeli soldiers had carried out the massacres. From that moment on, he ended up letting go of any fear of being labelled anti-semitic for telling the truth about what he saw. He would go on to become a harsh critic of Israel and its policies toward the Palestinians. For this, he would receive an unending stream of hate mail, “for the internet,” he wrote in 2014, “seems to have turned those who do not like to hear the truth about the Middle East into a community of haters, sending venomous letters not only to myself but to any reporter who dares to criticize Israel — or American policy in the Middle East.”

The Independent, in tribute to its most famous journalist, carries “the best of Fisk” on its website, and one of the articles it highlights is his January 30, 2010 article, “ Why does the US turn a blind eye to Israeli bulldozers?”

Both the United States and Europe, Fisk writes, “now stand idly by while the Israeli government effectively destroys any hope of a Palestinian state; even as you read these words, Israel’s bulldozers and demolition orders are destroying the last chance of peace; not only in the symbolic centre of Jerusalem itself but — strategically, far more important — in 60 per cent of the vast, biblical lands of the occupied West Bank, in that largest sector in which Jews now outnumber Muslims two to one.” Some 300,000 Israelis, he points out, “now live in 220 settlements which are all internationally illegal — in the richest and most fertile of the Palestinian occupied lands.” He wrote that 22 years ago. The situation of the Palestinians has only become worse under the Trump administration. (See companion articles this week in Toward Freedom, one on US policy toward occupied Palestine, the other on destroyed EU projects in Palestine) The recent visit of U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo to the West Bank — the first by a high American official — signals Trump’s plan to declare Israel’s illegal settlements as legal. Pompeo also declared that the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement would, from hereon in, be declared anti-semitic.

The Independent has also reproduced Fisk’s articles on Lebanon’s disintegration, both before and after the August 4, 2020 explosion of ammonium nitrate that destroyed Beirut’s port and the neighborhoods that surrounded it. His immediate reaction reveals his love of the region and its peoples, and his lament that Lebanon had effectively become a failed state: “So here is one of the most educated nations in the region with the most talented and courageous — and generous and kindliest — of peoples, blessed by snows and mountains and Roman ruins and the finest food and the greatest intellect and a history of millennia. And yet it cannot run its currency, supply its electric power, cure its sick or protect its people.”

.

Had he lived, he probably would have dug deeper into what caused the explosion, since ammonium nitrate does not self-ignite. He had little faith in the government of Lebanon to get to the bottom of it. “Not one major political murder in Lebanon — of presidents, prime minister or ex-prime minister, of members of parliament or political parties — has ever, in its history, been solved. “

And indeed, as investigations into the explosion continue, there has yet to be an answer as to what caused them. So Fisk, shortly before his death, was left with asking questions: “How on earth could 2,700 tons of ammonium nitrate be stored in a flimsy building for so many years after being removed from a Moldovan ship on its way to Mozambique in 2014 with no safety measures taken by those who decided to leave this vile material in the very centre of their own capital city?

“And all we are left with,” he concludes, “ is the towering inferno and its cancerous white shock wave, and then the second mushroom-shaped cloud (let us mention no other).”

Could his allusion to a mushroom-shaped cloud suggest that he considered some kind of bomb had caused the explosion? After all, wasn’t it President Trump who first announced that the explosion was caused by a bomb, only to be corrected by Pentagon officials who insisted that it was an accident?

Final Thoughts

As I reflect on Fisk’s life as a reporter, I think of how his experiences cause me to reflect on mine. His flat-out statement in the film that “the idea that you must not take anybody’s side is rubbish” hit home, conjuring up a memory from my days in Beirut.

I was hosting a small gathering of foreign correspondents in my apartment. The year was 1975, at a time right before Lebanon erupted in civil war. I was a reporter for the English language Beirut Daily Star. The subject of the Palestinians came up. I can’t recall the exact context, but it may have been related to my watching from the rooftop of my apartment Lebanese French mirage jets flying overhead and then dropping bombs on a nearby Palestinian neighborhood in Beirut. I expressed concern to my colleagues, and I will never forget the Washington Post reporter reprimanding me: “Now now. As a journalist You mustn’t take sides. You have to be objective!”

There was no Robert Fisk there to validate my feelings of shock and dismay. (He arrived a year later). As far as I was concerned, there were objective realities on the ground (and in the air) called facts and it was our duty to report the facts as we saw them. Or as Fisk put it, “my job as a journalist is to tell the truth.”

The Palestinians never got equal time back then. It got so bad for them that they ended up highjacking airplanes to draw attention to their cause, having faced global indifference for decades to the fact that they had been dispossessed from their lands in 1948 to make room for the state of Israel. Their highjacking tactic surely didn’t win them many friends and earned them the moniker of “terrorists,” which stuck even harder when they took up arms against the Israelis along the Lebanese border. When the Lebanese civil war erupted in April, 1975 after some Christian right wing militias fired on a busload of Palestinians, I chose to return to the States (having been shot at in a Beirut suburb) and it was then that I learned how incredibly biased the US media was against the Palestinians in particular and the Arabs in general. The slighted expression of sympathy for their plight got one branded as “anti-semitic,” which convinced me to turn to investigating the genocide of Amazonian indians in Latin America rather than be branded with that devastating slur and censored. Fortunately, Fisk took over where I left off, arriving in Beirut in 1976 just as the civil war was raging and for the next 44 years bravely reported the truth as he saw it.

Both of us learned that by delving into the history of the region, it became more understandable. In 2007, he published a 1000 page tome on this history: The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East.” Had I had the chance to meet him, I would have asked why the subject of oil only showed up on two pages in the book’s index “as a motive for the Iraq war.” To be fair, on page 932 he struck home when he wrote: “Israeli and U.S. ambitions in the region were now entwined, almost synonymous. This war, about oil and regional control, was being cheer-led by a president who was treacherously telling us that this was part of an eternal war against ‘terror.’”

He went on to write that the British people didn’t wish “to embark on endless wars with a Texas governor-executioner who dodged the Vietnam draft and who, with his oil buddies, was now sending America’s poor to destroy a Muslim nation that had nothing to do with the crimes against humanity of 11 September, 2001.”

Like Fisk, I have my father to thank for my determination to tell the truth about the Middle East. Daniel Dennett was also involved in World War II, first as a spy of the Office of Strategic Service and later as American’s only master spy in Middle East for the Central Intelligence Group (immediate precursor of the CIA). He died when I was six weeks old in a mysterious plane crash in 1947 following a top secret mission to Saudi Arabia, so I didn’t know him and couldn’t talk to him about his experiences. But he left behind a treasure trove of letters and reports which ended up in a steamer trunk in the Dennett family attic.

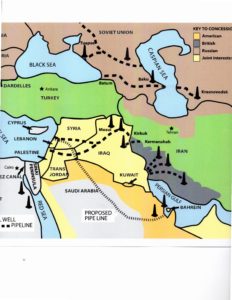

His last report convinced me that his final mission — to Saudi Arabia –was all about oil. In fact, it was all about the planned route of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline and whether this strategically important pipeline would terminate in Haifa, Palestine or in Lebanon.

in Chapter 2 of my book, I describe my quest as “Seeking truth, finding oil. “As part of my investigation, I would “follow the pipelines” both forward and back in time . Going back took me to the Iraq Petroleum pipeline which terminated in Haifa and had much to do with the 1917 Balfour Declaration in which Britain’s Foreign Secretary, Lord Balfour, promised a Jewish homeland in Palestine for European settlers to Lord Walter Rothschild, scion of the Rothschild oil and banking fortune. In short, there is an oil and pipeline connection to the formation of Israel, and this pipeline again became a “motivating force” for the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, namely, to reopen that pipeline (built in 1932 and closed in 1948 during Israel’s war for independence ) once Saddam Hussein was replaced by a pro-Israel Iraqi named Ahmad Chalabi, the creator of the false weapons of mass destruction pretext for the war on Iraq. Benjamin Netanyahu gleefully announced, “soon the oil will flow to Israel. This is not a pipe dream.” But, in it was, once the WMD charade discredited Chalabi as the US’s next puppet in the Middle east.

Soon, in my quest to understand the role of oil and pipelines in my father’s death and the Middle East’s endless wars that followed up to the present, I would seek out articles by Fisk. I learned that he had no illusions about what was causing these wars.

In a prescient article about the folly of invading Afghanistan, he issued a warning to George W. Bush and NATO about starting a new round of geopolitical warfare. “Perhaps,” he slyly wrote, “we could all go back to the history books before suggesting — and the idea of such an adventure is clearly being dreamed of in Washington — that the Great Game should be taken up once more.”

His warning, alas, went unheeded and by the time the documentary on him was released, Fisk was openly fearing that “what we write doesn’t make a difference.”

Yet he could take comfort in giving talks before legions of young students in the Middle East, many attending the American University of Beirut, telling them that he understood their anger over the injustices meted out to the peoples of the region by colonial powers.

In his historical explorations, he probed deeply into the genocide of Armenians, having learned in 2010 that “The US wants to deny that Turkey’s slaughter of 1.5 million Armenians in 1915 was genocide. But the evidence is there, in a hilltop orphanage near Beirut.”

This may explain why he acknowledged, in the film, that his reporting had developed a body of evidence on the wars in the Middle East “so no one can say, ‘This didn’t happen.” In an age where powerful leaders still engage in willful blindness and genocide denialism, Fisk has bestowed upon a new generation the best that journalism can offer: the unrelenting pursuit of the truth.

Charlotte Dennett is Guest Editor of Toward Freedom. Her most recent book is The Crash of Flight 3804: A Lost Spy, A Daughter’s Quest, and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil.

.

.

.