Management at Carrier Corporation pulled Donnie Knox, president of the United Steelworkers Local 1999, and others employed by the company into a meeting on February 10th. Knox and his fellow workers were informed their jobs would be moved to Mexico.

Despite remaining profitable in Indianapolis – the company boasted more than $7 billion in profits last year and was able to award their CEO a $10 million pay package – Carrier and its parent company United Technologies abruptly decided its 1,400 workforce in the Midwest would be discarded so manufacturing could be relocated to a site where, according to union staff, the company will pay workers just $3 per hour.

Employer-initiated plant closings are nothing new for American workers in the old rust belt. The factory shutdowns are also old hat for the USW who, like other labor unions, has adjusted its own game plan accordingly.

In 2012 the United Steelworkers formally joined forces with Mondragon, the long-lasting worker-owned company in the Basque region of Spain, to promote a “union co-op model” for creating sustainable jobs and communities. The popularity of unionized worker co-ops, those worker-owned enterprises in which employees affiliate with a labor union to advance their rights as workers, appears to be growing.

The challenges unionized co-ops historically faced, however, continue to affect the evolution of real-life alternatives to traditional capitalist business.

Union Co-ops in History: Early Antagonisms and Enduring Ideas

While the popularity of the model seems new, the idea of unions serving as vehicles for the establishment of cooperatives has a history, a contested history shaping the development of union co-ops still today.

When a steel mill in Youngstown, Ohio shutdown on September 19, 1977, some five thousand workers lost their jobs. Reports reached the public that “Black Monday,” which lives on in infamy in the historical memory of steelworkers, led some of those previously employed at Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company to head out to their garage and put a pistol to their heads.

As Gar Alperovitz documents in his book, “What Then Must We Do: Straight Talk about the Next American Revolution,” that was not on the only response.

Rank-and-file rabble-rousers in the USW local started organizing to transfer the mill to ownership of and control by those who had worked within it. Yet USW higher-ups, Alperovitz observes, “thought of the young steelworkers in Youngstown as upstart troublemakers who might also perhaps one day cause problems for the established national union leadership.”

Despite community support, the steelworkers who hoped to convert the plant into a worker-owned and collectively-run cooperative (worker co-op) never received the loan they were promised by the Carter administration to make the initiative possible. Rumors abound that the national union leadership, conspiring with big steel corporations, thwarted the deal.

The steelworkers’ support for worker co-ops, which did not end there, and the antagonism – as well as collaboration – with labor unions epitomizes the tension-filled, if also transformative union co-op movement.

“One of the problems with staking a business that has failed and trying … to turn it into a business that doesn’t fail, is that it failed for a reason,” said a present-day spokesperson for the USW who preferred not to be identified by name. “You know if the market for steel is depressed because of a flood of illegally traded foreign goods, then changing the owner of the company that sells steel isn’t going to make a difference in the bottom line.”

The USW staff member added that within the capitalist world economy, the global market determines the price for steel and other commodities union members make.

“Right now we’re in a situation where there’s a global over-capacity in steel-making,” he added. “We’re talking about hundreds of millions of tons per year. A lot of that ends up, we use the word ‘dumped’ – it’s a specific term that we use to refer to imported steel that ends up on our shores and penetrates our market because wherever it was produced, whether it’s China or South America or Russia or wherever, it isn’t needed. So they dump it here. And often it’s product that was subsidized to begin with so it doesn’t matter what they sell it for.”

He said he could understand the USW leadership not immediately embracing employee ownership in Youngstown. Union staff likely told workers there that the plant was closing not because the employees ran it inefficiently, but because the company could not sell the product.

“Had the union tried to buy a steel company that was deeply in the red and tried to turn that into a profitable business,” he said, “we would’ve failed, and it may have led to the demise of the union.”

Chris Cooper, program coordinator at the Ohio Employee Ownership Center, said the USW soon started experimenting with other forms of worker ownership, though, through Employee Stock Ownership Plans, or ESOPs, in the 1980s and 1990s. Given the poor financial situation of many of the companies involved, ESOPs had greater appeal than co-ops because the former offered tax breaks as key components of the deals the union negotiated.

The USW created the Worker Ownership Institute in the early 1990s, and Cooper said the OEOC became actively involved in myriad unionized worker ownership deals. In 1998, former OEOC director John Logue published a best practices manual, “Participatory Employee Ownership” for the WOI with the aim of increasing worker participation at unionized ESOPs because, as Cooper notes, they “are not by default as democratic as co-ops.”

Unfortunately, Cooper added, many companies that implemented ESOPs already suffered irreparable financial distress, which led to both union concessions and procurement of capital from outside sources. The union compromises bred distrust of worker ownership, while the outside investment diluted ownership. Many in the labor movement came to associate workplace democracy with its denatured practice in struggling ESOPs as a result.

“That kind of tainted employee ownership as a movement, especially with the unions, I think for a few decades,” Sushil Jacob, supervising attorney at the East Bay Community Law Center and author of “Think Outside the Boss: How to Create a Worker-Owned Business,” said, “because unions viewed ESOPs as management attempts to offload troubled, high debt-laden companies onto the workers and basically put the debt onto the workers’ backs.”

Some union ESOPs still survived. A few even thrived. The stigma attached to worker co-ops related to their small business reputation and supposed irrelevance to larger industrial unions like the USW also waned as a closer study of the Mondragon Cooperative Corporation in Spain led to a working relationship between the men of steel in the US and the decades-old Basque region-based enterprise that now employs more than 34,000 workers in some 100 different worker-owned and affiliated firms. The USW-Mondragon partnership spurred formation of new unionized cooperatives in the US.

In Madison, Wisc., a one-time bastion for organized labor, the city government just allocated one million dollars annually to fund worker cooperatives.

“Several of our local labor unions have been involved in planning how we’re going to operationalize that grant,” said Anne Reynolds, executive director of the Center for Cooperatives at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “So they’ve been really at the table right from the beginning on that.”

A New Era of Successes and Challenges

Recent successes notwithstanding, concerns persist in the context of today’s union co-op movement. Members of United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers of America Local 1100 successfully converted the failed at Republic Windows and Doors company in Chicago into a unionized, worker-owned cooperative several years after their high-profile sit-down strike at the Goose Island factory in 2008.

Their journey since then has not been easy. Only 17 of the original 240 workers remain. Under competitive economic pressure, the remaining workers at what is now known as New Era Windows pay themselves around minimum wage.

The difficulties are not limited to the cases of failed companies being converted by union activists into worker-owned co-ops either.

Diane Holmes, 65, has worked for Cooperative Home Care Associates in the Bronx for six years, yet she also makes only $10 an hour. The CHCA formed in 1985. Workers at the co-op were organized by the SEIU a little more than a decade later.

Holmes’ union, 1199SEIU, has been leading the Fight for 15 for all home care and health care workers in New York City. The local also benefits its CHCA worker-owner members, she said.

“The union involvement with the cooperative has been successful because we get together,” Holmes said. “We also have meetings when we have grievances – maybe a home health aide has a problem and it wasn’t maybe addressed by the coordinator, and they felt it wasn’t addressed properly. We take it to our union organizer, and our union organizer is able to set up a meeting, usually with [the co-op CEO] and members of administration at Cooperative, and we’re able to resolve the problem.”

Similar successes and challenges face unionized co-ops in the Midwest. In Cincinnati, Ohio, at the Our Harvest cooperative, an organization affiliated with the UFCW and committed to increasing access to healthy local food, the lowest paid worker also makes only $10 per hour, according to Kristen Barker, the executive director of the Cincinnati Union Co-op Initiative, a non-profit incubator for unionized co-ops that helped Our Harvest get off the ground. But, Barker adds, the workers receive a $450 per month stipend for health care, and farmers at the co-op are paid for overtime, which is not legally required nor the norm for many agro-businesses.

It tends to be easier, she said, for cooperative start-ups and conversions to co-ops in other industries like manufacturing that can deliver higher wages. Our Harvest expects to break even and generate a surplus as soon as this fiscal year, but it hasn’t happened yet.

The cooperative’s employees benefit from part ownership but also from their union, which has protected the rights of workers at the enterprise since its inception. At one point, when the co-op started over-relying on one farm manager, power imbalances negatively impacted the workplace. So the local initiated a grievance process. The standard union procedure addressed the problem.

The two-year collective bargaining agreement between the union and the cooperative just expired, and the UFCW is meeting with workers on Thursdays during the most heavily staffed work hours – something most employers do not want or allow – to prepare for another round of negotiations.

Barker said Our Harvest – like other CUCI initiatives including Sustainergy, a worker-owned energy savings company, and the Apple Street Market co-op on the Northside of the city – closely follows the USW-Mondragon union co-op template. While the USW forged the monumental partnership with Mondragon, she noted, it was done in such a way that put the onus on other unions to organize workers in co-ops across the country.

The USW offered CUCI a $12,000 loan to get their recent projects off the ground, while the UFCW made a $10,000 contribution to assist in the incubation process.

Currently, the required capital contribution for Our Harvest workers to become worker-owners is $3,000. However, workers can agree to have a certain amount taken out of their paycheck every two weeks to go toward the initial capital investment needed for worker-ownership; if they do, they get full voting rights immediately, although their profit-sharing receipts must go toward paying off the share.

In contrast, the Nursing and Caregivers Cooperative, Inc., a forthcoming association of Licensed Vocational Nurses incorporated under California’s new cooperative corporation law, will require just $500 as an initial capital contribution for all members, per the entity’s already-formulated bylaws. The Oakland-based NCC workers will be organized by the Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West.

It is no secret, said SEIU-UHW West Research Coordinator Ra Criscitiello, most trade unions appear to be knocking on death’s door more forcefully than they are challenging wealth disparities and related class relations.

“Organized labor has largely retained its same tactics and world view despite the reality that economic structures capturing employment have been turned on their heads,” Criscitiello said. “If unions cannot solve labor’s woes, it may not be that organized labor is dying—but rather that it needs to transform.”

Criscitiello claims the SEIU-UHW West is aiding LVNs in the Bay Area as they reclaim the so-called “sharing economy” for working people. What passes for “sharing” usually translates into increasingly insecure work with scarce or nonexistent benefits.

Some union strategies advocate an industrial organization model to fight the diminution of workers’ rights (e.g. workers’ comp, health benefits, sick leave, and retirement savings) through large-scale structures designed to ensure benefits are not contingent on a workers’ relationship with a particular employer. A smaller-scale path, modeled on pre-industrial guilds with a high-tech twist, entails monopolizing the labor supply in a market so unions can use institutional weight “to promote an employment paradigm where workers own their own labor and have portable benefits,” Criscitiello explained.

LVNs in the East Bay are choosing the latter. The “sharing economy” might be insidiously anti-union now, but by partnering with a tech start-up partner developing new mobile technologies, SEIU-UHW hopes its NCC worker-owners – in California, these LVNs are largely women and immigrants – can redefine what a flexible workforce means and how it can operate for the benefit of all involved.

Jacob, who through his work at the East Bay Community Law Center became the corporate counsel for the emerging NCC, said the co-op will service a smart phone app enabling people to put in calls for home health visits with near-instantaneous responses.

The co-op plans to utilize the new technology so nurses can be dispatched on-demand to patients’ homes via communication through those networked devices. Equally integral to their emergent cooperative structure, though, is the collectivization of labor to better bargain worker value and leverage buying power to purchase employee health insurance on scale at affordable prices.

“The nurses on the app are all owners of the co-op,” Jacob added, “and the co-op has part ownership of the app itself.”

Alternative Approaches to Evolving Alternatives for Organized Labor and Workplace Democracy

In addition to organizing New Era Windows in Chicago and a slew of other worker-owned enterprises in Vermont, the UE has recently concentrated efforts on unionizing consumer cooperatives. A consumer co-op is a business wherein those who shop at the store can buy in to become member-owners each with one vote for the board of directors overseeing operations.

Chad McGinnis, a field organizer who helped employees at City Market Co-op in Burlington, Vt. affiliate with UE Local 203, said he has noticed the majority of consumer co-ops tend to follow a certain trajectory.

“Presumably it’s like community control over your grocery store,” he offered. “You can get better food, and it’s local and healthy. … But the reality is these are businesses operating under capitalism. They’re subject to all the same pressures that any business operating under capitalism is subjected to. They got to grow. They go to make a profit. Quantity changes into quality; they hit a tipping point where they adopt a sort of conventional internal hierarchy, a conventional management structure. And they start to hire employees. And then those employees have a boss. And then that boss has a department manager. And there’s a general management over the store.”

That happened at City Market around 2002, and unionization followed shortly thereafter. Although, it was not without roadblocks. The co-op was in fiscal trouble, and the general manager at the time told workers contract negotiations would have to be put on hold at one point because he was going to Disney Land.

Workers at the co-op took a tip from the boss: although they did not go on vacation, they did stage a walk-out, which led to, eventually, to a decent contract.

UE field organizer George Waksmunski, who helped organize workers at the East End Food Co-op in Pittsburgh, said unions might play an even greater role in these consumer-driven arenas than they do in organizing employee-owned firms.

“The more and more you get into the realm where you’re driven by a board of directors and a management team, the workers get alienated,” Waksmunski said about the devolution of democracy in consumer co-op jobs.

A consumer co-op can be nice place to work, he qualified, but having a voice and some footing is still important.

“If you don’t have your own union that you can go to with your fellow workers – and a method to address your grievances – then you’re just left hanging, you’re still left hanging out in the cold just like any other worker,” he said, adding workers at co-ops also generally “get it so much quicker than most workers do because they come from a more progressive background.”

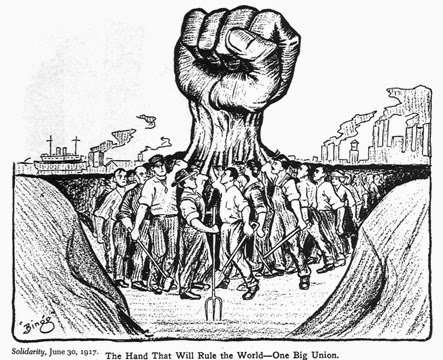

Waksmunski said the board of directors at East End probably backed off of anti-union campaigning – standard union-busting strategies from which even cooperatives are not immune – because they did not want any additional controversy after a “very nasty” struggle that took place previously between management and the Industrial Workers of the World. Waksmunski said the East End workers’ campaign with the IWW, a long-standing international organization advocating “One Big Union” to form “the structure of the new society within the shell of the old,” as the Wobblies’ preamble states, had been aggressive. He said some employees were turned off by the tactics.

In the Twin Cities of Minnesota, however, workers at what was supposed to be a collectively-run non-profit recently used the 111-year-old IWW union as a direct action-driven vehicle to reach a new destination: real workplace democracy.

Sisters’ Camelot, a formally 501(c)(3) organization, hires canvassers to do door-to-door solicitations so the company can collect and distribute food to low-income communities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. The company claims to – and might once have – operated as a cooperative with collective governance, but workers at Sisters’ Camelot felt the need to affiliate with the IWW to address myriad workplace grievances. When management refused to negotiate with the newly formed Sisters Camelot Canvass Union, the Wobblies went on strike.

Later, the National Labor Relations Board found that one of the company’s canvassers, Christopher Allison, was wrongly fired for engaging in union activity.

The non-profit’s management also engaged in quite literal union-busting. Not only did they try to dissuade workers from participating in protected union activity, as the NLRB confirmed. According to Allison, Sisters’ Camelot supporters also physically threatened IWW-affiliated canvassers on picket lines.

The September 2015 NLRB decision also found that, contrary to the claims of Sisters’ Camelot, canvassers should not be considered “independent contractors” bereft of basic workers’ rights. Allison contends the NLRB ruling could be precedent to expand labor rights to other misclassified “independent contractors” across the country, from Uber drivers to various construction workers.

While out on strike in the summer of 2013, Allison and several other former canvassers also formed their own food justice non-profit, the North Country Food Alliance. In between distributing to those in need more than $250,000 worth of mostly surplus organic produce that would otherwise go to waste, the worker-run enterprise has also employed more than 12 Wobblies who help maintain multiple community gardens throughout the Twin Cities and host monthly classes on foraging for wild foods.

“Every worker who works for the organization has an equal, democratic vote at weekly meetings that decide all matters of the organization,” Allison said in an interview on the Heartland Labor Forum. “And we are all members of the Industrial Workers of the World to protect that process so that it can’t be hijacked.”

No one at the new union shop has disciplinary hiring or firing power over anyone else. While not officially a unionized co-op, North Country Food Alliance highlights the panoply of old and new approaches for advancing the labor movement to extend workplace democracy.

“Even though we really wanted our bosses to negotiate when we unionized at Sisters’ Camelot – and we expected them to, naively – we’re glad at this point that they didn’t because now we’re better off than we could have ever been with any deal that we would have ever gotten out of our bosses. Now we don’t have bosses, and that’s fantastic.”

James Anderson is a freelance writer, journalist and social theorist. His academic writing has appeared in journals like Critical Studies in Media Communication and the International Review of Information Ethics. His news stories, editorials and commentaries have been featured in outlets including Truthout, In These Times, Toward Freedom, ROAR Magazine, ZNet, Counterpunch and The Partially Examined Life. He recently defended his doctoral dissertation and will graduate with a PhD in Mass Communication and Media Arts from Southern Illinois University Carbondale in May 2016.