Between the fall of 1999 and April of 2000, hundreds of thousands of factory workers, peasants, retirees, students, professionals, and everyday people took to the streets in Cochabamba, Bolivia, to fight the privatization of their water. A foreign-led consortium of private corporations had taken control of the city’s water supply, increasing water prices by as much as 300 percent. With the skills and experience of organized movements such as the Federation of Factory Workers, working people were able to defeat a multibillion-dollar corporation around a shared interest: the right to water.

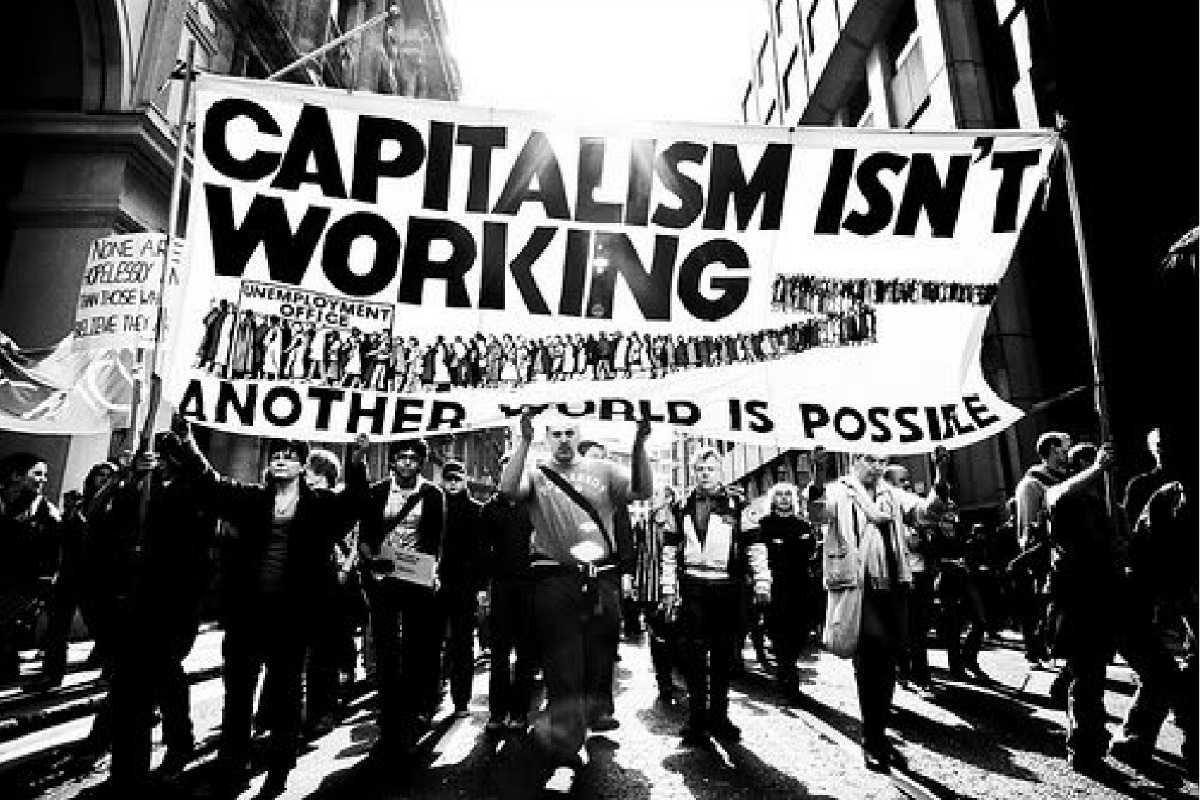

In the face of a well-organized global elite that has gutted the power of workplace organizing, Cochabamba shows us that organizing the working class around a common interest and moving beyond the confines of the workplace provides an opening to push for—and win—a future that centers people over profit.

The Geography of the Present

Capitalism began to take on a new form in the 1970s with the arrival of new technologies that facilitated the rapid transportation of goods and communication about the production process. Neoliberalism, a policy framework that enriches the wealthy (by cutting taxes) and that demeans workers (by cutting opportunities and access to social wages), came to define the global economy.

The world was now connected in a way that enabled global capitalists to break up the production process, making it even more difficult for organized masses of working people to halt the production process and garner real power over the ruling elite. Now that the manufacturing of parts of the production process was spread across the world, the shutdown of a factory that manufactures car engines in China could easily be offset by the production of car engines in Mexico or Taiwan.

Vijay Prashad, director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, explains that “new technologies—such as satellite communications, computerization and container ships—provided firms with the ability to manage global, real-time databases and to move goods as fast as possible. Firms could break up factories and set them up in several countries at the same time—a process known as the disarticulation of production.” Advances in transportation further enabled this process so that “capital could move the parts of the commodity swiftly and relatively cheaply as well as shift commodities to markets with relative ease.”

This scenario is vastly different from the power generated—for example—by auto workers in Detroit in the mid-twentieth century, who were able to shut down the entire production process through strikes and slowdowns, and whose benefits and union contracts reflect the level of power they were able to exercise over their employers. Factories that were once the heart of the auto industry and the site of powerful worker organizing are now largely abandoned, their broken windows and crumbling walls a mirror of the changing landscape of production and the need for different strategies to organize around it.

The context for organizing today that faces working people across the world is one that must grapple with the challenges posed by a decentralized production process and a well-organized ruling class. We can see the current moment as a rupture of sorts—perhaps a way of understanding the global rise of fascism. Scapegoating in the form of xenophobia, racism, and religious fundamentalism—the well-worn tools of capitalism’s strategy to divide the working class—fills an ideological void and presents a solution to the anger stoked by the everyday realities of the working class who are faced with massive inequality and pauperization. It is to this anger that the left must respond; to provide an ideology that seeks to understand its origins and to shape cultural mechanisms and ideologies that allow us to imagine—and build—a different path forward.

Seeds of Resistance

The Center of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) presents one such path. In a recent interview, CITU president K. Hemalata discussed both the challenges that lie ahead of working-class movements as well as some of the strategies that are being used to combat them. Hemalata points to the same trend of the disarticulation of production, that “Workers do not produce the entire product; often they produce just a part of the commodity.” She explains that “This means that the workers are not concentrated in one factory, where they can get organized. Rather, they are working on just a part of the commodity, spatially separated from fellow workers, and have less power because of this.”

Another major problem, she explains, is the use of migrant labor to create “social fissures” between the workers and surrounding communities. Often, workers from one state are loaded onto a bus to a factory elsewhere, where they have no ties to the community and often do not speak the same language. This trend is mirrored in the forced migration of those fleeing violence in Central America in search of safety and economic opportunity in the United States. Migrants who succeed in their passage to the United States are often blamed for the woes of the broader working class for “stealing jobs,” deflecting the blame from the capitalist class for keeping all wages low and for having created the unstable conditions in their home countries through imperialist interventions.

Despite the shared interest between the community and the workers and between divided sectors of the working class who are forced to accept low wages and often precarious conditions, these divisions often succeed in creating social fractures that reinforce the interests of the ruling class.

One strategy used by CITU to combat these social fractures is “to organize people in their residential areas and not just at the places of production,” says Hemalata. In the south Indian state of Kerala, for example, the Left Democratic Front offers Malayalam language classes for the migrant workers, which “allows them to develop closer ties with people who live beside their places of work and in their neighborhoods. If you provide workers with the means to enter the society where they work, then the divides cannot be so easily exploited by management.”

The challenges posed by global capital require creativity in their solutions. We must rebuild the imagination of the working class and combat the capitalist narrative that has made it easier for us to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Before a new system can be born, its seeds must be planted and nurtured in the fissures of our current reality. We must build and popularize an ideology and culture that offer a solution other than hate and scapegoating to the woes experienced by the poor and dispossessed—and amplify the theories and strategies that exist among popular movements today. This requires confronting the consumer-driven culture and social isolation promoted by capitalism and building one that revives community and humanity, that centers the well-being of humanity over the accumulation of wealth at the hands of the few. The seeds of the future exist in the strategies of CITU in India; in the worker-cooperatives in Brazil; in the housing struggles in South Africa; and in countless other popular movements across the world. These are the wrenches that can halt the wheels of the well-oiled machine of capital.

Celina della Croce is a coordinator at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research as well as an organizer, activist, and advocate for social justice. Prior to joining Tricontinental Institute, she worked in the labor movement with the Service Employees Union and the Fight for 15, organizing for economic, racial and immigrant justice.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.