One penny more! This has been the simple demand of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), an organization which for almost 20 years has been fighting for dignity and justice for migrant farmworkers in the tomato fields of South Florida. This has been the simple demand of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), an organization which for almost 20 years has been fighting for dignity and justice for migrant farmworkers in the tomato fields of South Florida. Through sustained pressure including nationwide tours, multi-day caravans, hunger strikes, flash mobs and more, the CIW has been able to change the face of the entire Florida tomato industry. As the state of Florida produces 90% of the tomatoes grown in the U.S. from November to May, this has had rippling affects on the nation’s agricultural industry.

The CIW, in partnership with the network Student/Farmworker Alliance, has successfully brought fast food giants including McDonalds, Burger King, Taco Bell and Subway and food service companies like Compass, Sodexo and Aramark to the negotiating table where they signed fair food agreements. These agreements guarantee one penny more per pound for the tomatoes they purchase from Florida farmworkers, a code of conduct and a voice for farmworkers within the industry.

With these victories in the bag, the CIW moved on to the supermarket industry. Publix supermarket is one of their principal targets with over 1000 stores across the southeast and billion dollar profits that consistently place it in the ranking of the top ten largest privately-owned US corporations.

With these victories in the bag, the CIW moved on to the supermarket industry. Publix supermarket is one of their principal targets with over 1000 stores across the southeast and billion dollar profits that consistently place it in the ranking of the top ten largest privately-owned US corporations.

Employing creative actions to engage Publix executives in dialogue, members of the CIW and allies marched 23 miles to the headquarters from the city of Tampa in 2010. In 2011, they biked 200 miles from the farmworker town where they are based, Immokalee, to Lakeland. Both times Publix refused to meet with the workers.

Fast for Fair Food

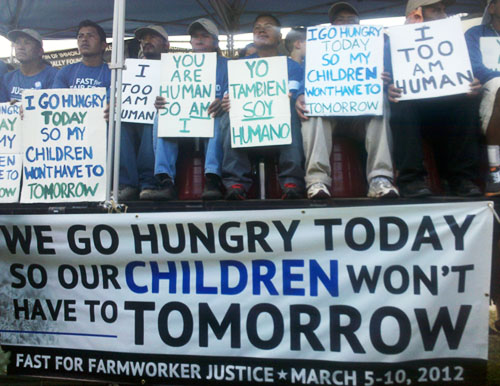

This spring, the CIW upped the ante with 60 farmworkers and allies holding a six day fast, camping out on the well manicured lawns of the supermarket’s Florida headquarters. The farmworkers, largely from Mexico and Guatemala, held signs saying “We Go Hungry Today, So That Our Children May Eat Tomorrow” and “Tambien Soy Humano, I Am Also Human.” CIW member Oscar Otzoy says they hold signs like this so that executives will recognize their humanity.

On his arm Otzoy has a pin that says, “I am not a tractor,” and explains why he wears it: “This is something for many years which the agricultural industry viewed us as – a machine. We are not machines. We are human beings and for that we deserve a life with dignity and respect.”

The CIW previously held two hunger strikes to protest abuses in the field and also to bring Taco Bell to the negotiating table. Lucas Benitez, who helped found the CIW nearly 20 years ago, says fasts and hunger strikes are effective peaceful tactics that they have learned from social justice leaders throughout history.

“[A fast is] a way to expose your enemy and their greed to the public, so that the public sees them. We are not rich people. We are poor people. We offer our bodies just to have a dialogue with people like the executives of this corporation,” says Benitez.

Hermelinda Cortés fasted with one child in tow and two left behind in Immokalee. She says she sacrificed being with her children during the fast so that they could have a better future. Cortés, originally from Oaxaca, Mexico says that life for female farmworkers with families is very difficult and that often they sleep less than 4 hours. She says farmworkers like herself get up at 4 in the morning, and have to wake their children to carry them to daycare, to go work in the fields – all before the sun has even risen.

Cortés challenges those who criticize the farmworkers: “Those who don’t support us, I would like to invite them to work one day picking tomatoes to see what our work is like. Many think that it’s easy… but I just ask for one day for them, to see if they would think the same after working one day.”

Publix supermarket did not respond to repeated media requests for this article, but issued a statement on their website regarding the “CIW issue.” In the statement they say, “Publix is more than willing to pay a penny more per pound or whatever the market price for tomatoes will be in order to provide the goods to our customers. However, we will not pay employees of other companies directly for their labor. That is the responsibility of their employer.”

Laura Safer-Espinoza the Executive Director of Fair Foods Standards Council, an independent organization set up to monitor the fair food agreements signed with the 10 major corporations says Publix statements hold no water.

“They don’t wish to pay other people’s employees. No corporate buyer in the program ever pays a farmworker directly; they pay their producers of Florida tomatoes just as they always have done. The only difference is because of a result of an appeal to conscience some purchasers are paying an extra penny,” says Safer-Espinoza.

While that extra penny may seem negligible to some, it would actually nearly double workers salaries as they currently earn around 50 cents for every 32 pound bucket of tomatoes.

Publix also stated, “As a community partner for more than 80 years, it would be unconscionable to believe that our company would support a violation of human rights.”

Fair Food Agreements and Basic Human Rights

Over the years, there have been nine documented cases of slavery in Florida’s fruit and vegetable fields involving more than 1,200 workers; the CIW has helped investigate and expose these cases. Because of racism embedded in the National Labor Relations Act from 1935, farmworkers were excluded from basic protections including the right to collective bargaining. This denial of basic workers’ rights lends agricultural fields to be ripe for abuses, which in its most extreme manifestation is slavery.

The Fair Food Agreements not only guarantees better wages for workers, but also ensures that employers have to pay workers for all the hours that they are present in the field. Before, workers would travel to the fields on company buses very early in the morning, but end up waiting for hours until the conditions were right to start picking, upon which their pay would commence. The agreements also guarantee workers basic things like drinking water and shade during lunch. If a worker feels sick they have the right to go home, something they couldn’t do before. Workers also now have access to a participatory health and safety program, a worker-to-worker education process and avenues for complaining about abuses to external monitors. The complaint resolution system is especially crucial for female farmworkers who often confront sexual harassment and abuse.

Northeast Supermarket Tour

Since CIW started targeting supermarkets only two have signed: Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods. Trader Joe’s was a recent victory in February 2012, following a nearly two year campaign against the specialty food market and a scheduled “break up day action” for Valentine’s Day in over 40 cities. The CIW is now challenging four other major supermarket chains including Kroger’s, Stop & Shop and Giant who are all owned by Ahold.

Farmworkers traveled up and down the east coast holding pickets and actions at the headquarters of Ahold in Carlisle, PA, Stop & Shop and Giant’s corporate offices in Quincy, MA. While the farmworkers took off ten days from work to spread their clamors for economic justice, company executives wouldn’t even take five minutes to meet with them. CIW members were joined at the supermarket headquarters protests by a broad swath of allies, including community members and students. They also played a visit to Chipotle in NYC which claims to sell “food with integrity,” yet for years have refused to come to the table with CIW.

Luis Larin works with the Baltimore based United Workers, organizing low wage workers who met with the CIW on their tour. He says the CIW’s model of worker organizing is the true way to create substantial change: “We have a systematic problem. People who understand the problem have to be at the forefront to creating the change. They are sick and tired of this injustice and can create the path to change. There is no other way.”

Also see this video on the CIW by Andalusia Knoll:

Andalusia Knoll is a multimedia journalist, communications strategist, educator and organizer. She is a member of the NYC based Community/Farmworker Alliance who work in alliance with The Coalition of Immokalee Workers. She is a regular contributor to Free Speech Radio News, The Real News Network, Upside Down World and Toward Freedom. Andalusia also works with Families for Freedom fighting deportations and detentions and the Medios Caminantes independent media network.