By Nikola Mikovic

The Western-backed Belarusian opposition has failed to topple President Alexander Lukashenko, who is still firmly supported by Russia. Three months after the Eastern European country held controversial presidential elections, anti-Lukashenko opposition groups still hold protests all over the country, although once massive demonstrations, involving some 100,000 protesters taking to the streets, are now dying down to several thousand. Belarus, located in the heartland of Eastern Europe, lies north of the embattled Ukraine, east of Poland and Lithuania, and west of Russia, and has been the scene of yet another East-West confrontation over energy routes to Europe, with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov accusing Belarusian opposition figures based in neighboring Poland and Lithuania of trying to destabilize the country.

Russia’s efforts to keep Belarus (which, translated, means white Russia) in its orbit goes back decades. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Belarus declared its independence in 1991. The country started its transition from communism to a market-oriented economy and changed its Soviet flag and symbols to those that were used during the short-lived Belarusian People’s Republic that existed from 1918 – 1919. Also, Belarus gradually started turning to the West. However, the situation changed in 1994 when Lukashenko won the first national elections held in Belarus since the nation seceded from the Soviet Union. He has been in power ever since and has been relatively successfully balancing between Russia and the West.

On August 9, according to Belarus’s Central Election Commission, Lukashenko won his fifth term with 80 percent of the vote. His major rival, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, received about 10 percent of the vote, which triggered large-scale protests in Belarus. Tikhanovskaya, as well as other opposition figures, accused Lukashenko of rigging the election. Most European Union member-states did not recognize Lukashenko’s victory and have recently imposed sanctions on the Belarusian leader and his allies. Neighboring Lithuania went so far as to recognize Tikhanovskaya as the Belarusian President. However, all these actions did not result in the overthrow of Alexander Lukashenko.

Tikhanovskaya fled Belarus after reportedly receiving threats in the aftermath of the election. Previously, Belarusian authorities arrested another prominent opposition figure – Viktor Babariko, a former banker, who spent 20 years working for the local unit of Russia’s Gazprombank. He was accused of siphoning $430 million out of Belarus in money-laundering schemes. In early September Maria Kolesnikova, who became one of the faces of the mass protests, was also arrested. At this point, the entire Belarusian opposition is either exiled, or behind bars. At the same time, Lukashenko is playing a divide and rule card. He is trying to form a “systemic opposition” in Belarus based on a Russian model where three out of four parties in the Russian Parliament are nominally opposition, even though they almost never criticize President Vladimir Putin. That is why Lukashenko recently paid a visit to the banker, Viktor Babariko, and other political prisoners still kept in jail. It is believed that he needs support from Babariko ahead of the coming constitutional changes, which is something that the Kremlin firmly insists on.

The Energy Factor

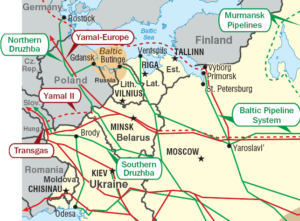

Over the years, Belarus and Russia have had numerous oil and gas disputes. The Kremlin has been providing cheap energy to its ally, subsidizing the Belarusian Soviet style-economy for two decades.

The Russian Federation also opened its market for Belarusian goods, even though it occasionally imposed bans on certain products, as a method of applying pressure on Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko. In addition, Belarus has received from Moscow credits worth billions of US dollars. Such a policy ended in January when Russia halted oil supplies to refineries in Belarus after authorities in Moscow and Minsk (the Belarusian capital) failed to renegotiate oil prices for 2021. Eventually, the two countries reached an agreement about future energy supplies to Belarus, although it remains unclear what will be the price for Russian crude oil and natural gas for Minsk.

In the past, Moscow firmly insisted on Belarus’ deeper integration into the Union State of Russia and Belarus in exchange for cheap energy. Lukashenko was quite aware that such a move would limit Belarusian sovereignty, as well as his nearly unlimited power as an independent republic. Now that he is sanctioned by the West, his room for political maneuver is rather narrow, which means that he may have to make some painful concessions. to Russia. Indeed, ever since the political crisis occurred, Belarus entered even deeper in Russia’s geopolitical orbit. Previously, the Kremlin clearly demonstrated that the policy of cheap energy for its ally was a thing of the past. In January Russia halted oil supplies to Belarus, which forced the former Soviet republic to start diversifying its energy imports. Lukashenko gradually intensified his anti-Russia rhetoric, and had already sought to improve relations with Western countries. In November last year, he visited Vienna and met with Austrian President Alexander Van der Bellen, and in February this year he hosted US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Belarus even reportedly bought 80,000 tons of US oil imported via Lithuania’s Klaipeda Port. That could be one of the reasons why Moscow, at the very beginning of mass anti-Lukashenko protests, hesitated from directly siding with Lukashenko. At the same time, some political figures close to the Kremlin openly said that the Belarusian leader must go. However, the .general line of the party in Moscow soon changed, and Russia provided necessary support to its client in Minsk. Lukashenko reportedly hosted Russian security officials several times, and his riot police started brutally dispersing protesters.

At the end of October, Lithuania-based Tikhanovskaya and the exiled Belarusian Coordination Council for the Transfer of Power staged a work stoppage in several state-owned Belarusian companies, hoping that such a pressure would force Lukashenko to make significant concessions to the opposition. The authorities did not have a hard time dealing with a national strike attempt. Strike leaders were either fired or arrested, and the opposition yet again failed to overthrow Lukashenko. Although anti-Lukashenko forces still hold demonstrations every Sunday, the number of protesters is declining, and the Belarusian leader managed to consolidate his power.

Although the Western-backed Tikhanovskaya and the Coordination Council will likely keep trying to find a way to weaken Lukashenko, he will stay in power as long as he is backed by Russia, as well as by the Belarusian security apparatus. His term ends in 2025, but since Moscow is pushing for constitutional changes which would transform the Belarusian political system from being purely presidential to a parliamentary republic, it would not be improbable for Lukashenko to step down earlier. In the meantime, Russia will likely try to cement its positions in Belarus.

Since the former Soviet republic does not have any significant natural resources, despite fears and speculations about the Kremlin’s alleged plans to annex Belarus, it is improbable that Russia will ever invade Belarus. Moscow sees its ally primarily as a reliable partner for the transit of Russian oil and gas to Western Europe. Belarus itself relies on Russia for more than 80 percent of its overall energy needs, and its export-oriented economy is heavily dependent on the Russian market. Finally, on November 7 the Eastern European nation officially opened its first nuclear power plant that was built by Rosatom, the Russian state nuclear corporation. That is another indication that, in the long-term, the country will likely preserve close ties with Moscow, with or without Lukashenko in power.

Nikola Mikovic is a contributor to CGTN, Global Comment, Byline Times, Informed Comment, and World Geostrategic Insights. He is a goepolitical analyst for KJ Reports, and Global Wonks