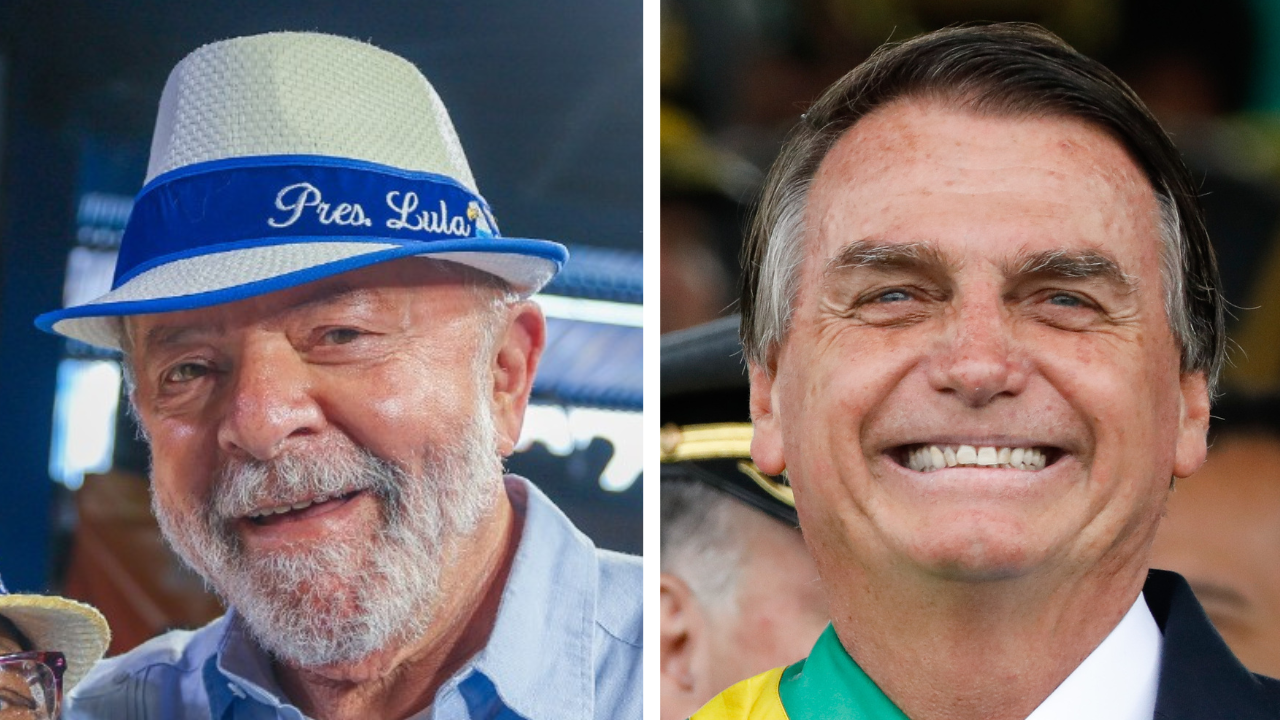

The Latin American Left is regrouping. On July 19, 2021, Peru’s National Elections Jury announced the official results of the 2021 presidential elections, declaring Pedro Castillo as President of Peru. An important voting survey in Brazil has revealed that Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva would outperform neo-fascist President Jair Bolsonaro in all scenarios for the 2022 elections in the country. Colombia is in socio-economic turmoil, creating a potential opening for the election of Gustavo Petro – a left-wing politician. In Chile, the result of elections held on May 15-16, 2021, for the 155-member new constituent assembly has thrust progressive candidates to the forefront of national politics. All these dynamics will regionally strengthen the leftist governments already in power in Argentina, Bolivia, Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. An anti-neoliberal shift in Latin America’s political compass carries global significance.

Imperialism

Large swathes of humanity who live in the peripheries of the world system have been witnessing a deadly process of absolute immiseration. Imperialism has restricted the economic growth of the periphery to mineral and agricultural sectors in order to assure raw materials for advanced capitalist nations. Hence, most Third World economies are heavily dependent on the export of primary commodities. In Latin America, such primary commodities account for the majority of exports for nearly all countries. While Latin American countries export primary goods to the Global North, they tend to re-import manufactured products from these same countries. The value added to these manufactured commodities – typically constructed from the primary inputs imported earlier – generates profit for northern countries while maintaining Latin American countries in a perpetual trade deficit.

While some countries in the periphery have facilitated a degree of industrialization through the surpluses accumulated from export-led growth, the disarticulated structures of these economies persists. The imperialist states’ monopolies – technological, financial, natural resources, communications, and military – has meant that there has been a lack of any significant indigenous technical development. Even to the extent that industrial growth has occurred, it has been based on the import of capital and technology, which has considerably reduced the dynamic effects on the economy that are usually associated with industrial growth. Moreover, a relocation of the locus of value creation from the core to the periphery means that the core relies less and less on the unprofitable exploitation of its own workers. Instead, the metropole increasingly divides the world into what has been labeled as Southern “production economies” and Northern “consumption economies.”

The main driver behind this process is undoubtedly the low wage level in the South. Entrenchment of extroverted economies like these has generated cut-throat competition amongst Southern firms for foreign capital. What we have now is a global race to the bottom, marked by a deathly spiral of exchange rate devaluations, hyper-low taxes and depressed wages. Multinational corporations based in the capitalist core have unendingly feasted on this wretchedness, fattening their profits from the extreme exploitation of the Third World’s large labor reserves. As such, the structure of today’s global economy has been profoundly shaped by the allocation of labor to industrial sectors according to differential rates of national exploitation. Thus, only the outward form of value transfers from the South to the North has changed, with the unequal exchange of products embodying different quantities of value steadily continuing. A large pool of precarized workers has been created, which consistently remains enmeshed in networks of informal economy, being forced by the productive configurations to enrich foreign capitalists and nourish the parasitic nature of the comprador bourgeoisie.

International Finance Capital

The continuation of the international division of labor and the creation of dependent industrialization has been complemented by the hegemony of international finance capital. Prabhat Patnaik writes:

“In the current phase of imperialism, finance capital has become international, while the State remains a nation-State. The nation-State therefore willy-nilly must bow before the wishes of finance, for otherwise finance (both originating in that country and brought in from outside) will leave that particular country and move elsewhere, reducing it to illiquidity and disrupting its economy. The process of globalization of finance therefore has the effect of undermining the autonomy of the nation-State. The State cannot do what it wishes to do, or what its elected government has been elected to do, since it must do what finance wishes it to do.”

The interests of the financial oligarchy lie in strongly opposing state expenditure financed either by taxes on capitalists or by borrowing – the only ways of financing through which the state can effect a net expansion in aggregate demand. Financial interests are against deficit-financed spending for a number of reasons. First, deficit financing is seen to increase the liquidity overhang in the system, and therefore as being potentially inflationary. Inflation is anathema to finance since it erodes the value of financial assets. Second, financial markets fear that the introduction of debt-financed spending – which is driven by goals other than profit-making – will render interest rate differentials that determine financial profits more unpredictable. Third, if deficit spending leads to a substantial build-up of the state’s debt, it may intervene in financial markets to lower interest rates with implications for financial returns.

Under these circumstances, even moderate welfarism has become a danger to the neoliberal order. Whereas the welfare state in the immediate post-War era served the ruling class by warding off the threat of communism, in the neoliberal era – where accumulation by dispossession has become the predominant mode of capitalist growth – even the most modest of demand management policies have had to face intense political opposition. Taking into account the internationally polarizing and nationally suffocating results of global capitalism, the slow resurgence of the Latin American Left will provide an avenue for the advancement of an alternative agenda.

The Experience of the Pink Tide

Firstly, progressive governments in the continent have always tried to tackle relations of dependency, as is discernible from their experience in power during the Pink Tide. In opposition to metropolitan control over mineral resources and plantations, the Latin American Left consolidated the public sector which displaced the dominance of foreign capital. These arrangements ensured that the revenues coming from the primary commodity sector were no longer siphoned off by the rich but were diverted towards the poor. The assertion of control over financial resources and their redirection toward social developmentalism was coupled with the uneven promotion of sovereign forms of industrialization, trade and finance through various initiatives like the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, the Union of South American Nations and the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America.

Before the public sector and regional groupings could be fully used for developing domestic heavy-industry base and technological capability, the commodity boom itself collapsed. This external event did not allow the Left’s redistributive strategy to transform into concerted attempts at changing the productive forces. However, the fact that a politico-ideological project of independence was advocated stands as a testimony to the fruitful possibilities contained in the Pink Tide. Industrialization, social welfare, and the nation came together in the notion of sovereignty; industrialization was not posed simply as a means by which Third World capitalists could accumulate capital more effectively, but as a means of improving the nation as a whole.

Moreover, a programme of selective delinking was supported which allowed Latin American governments to self-determine which sector of the economy could be safely opened up. They could differentially open up a sector where foreign capital was needed to supplement local capital in whole or in part. As part of this blueprint of economic self-determination, clear-headed campaigns were initiated to resist pressures to liberalize the financial sector. In fact, Latin America’s leftist governments tended to increase the level of capital controls instead of merely adapting to the constraints imposed by financial globalization. The reregulation of cross-border financial flows was part of a coordinated effort to obtain further macroeconomic policy autonomy and attend to the interests of impoverished constituencies.

The existence of capital controls enabled the Latin American Left to temporarily soften the impact of the end of commodity boom. One of the visible ways that the collapse of primary commodity prices makes itself felt is through a shortage of foreign exchange to finance necessary imports. This gives rise to inflation, to currency depreciations which further aggravate inflation, and to shortages of essential goods. Further, the reduced incomes -a result of the slump in the primary commodity demand – cause recession, stagnation and unemployment. The conservation of foreign exchange for importing essential commodities, and the prevention of outflow of foreign exchange by wealth-holders hedging against exchange rate depreciation, become extremely important. Towards this end, the Latin American Left’s regulatory management of banks and foreign trade proved to be crucial in mitigating the effects of changing global conditions.

Secondly, Latin American leftist governments extensively used planning and welfare policies, such as conditional cash transfers (CCTs), financed through the receipts of economic growth and the taxation of rising commodity exports. Under a new socio-economic structure of accumulation, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates increased and social conditions improved, reversing the adverse consequences of neoliberalism and cementing popular support for the Pink Tide administrations. The GDP per capita of Latin America and the Caribbean rose by 31% between 2003 and 2013, poverty rates fell from 32 to 17%, and the country-average of the Gini index of household per capita income in Latin America fell by 0.06. All this stood in complete contrast to the past implementations of harsh austerity programs and fiscal niggardliness which were intended to restore government’s “credibility” and return to the elusive cycle of growth led solely by private investment.

The implementation of welfare policies needs to be looked in the specific context of contemporary capitalism. In a global situation marked by the hegemony of international finance capital and calcified hierarchies, the unleashing of successful poverty alleviation schemes, increase in minimum wages, strengthening of labor regulations and the weakening of deficit targets were not acceptable to the elites who saw these policies as a precursor to more radical shifts. Thus, in an era of finance capital where even the most basic welfare spending runs contrary to the interests of an inflation-fearing financial oligarchy, the Latin American Left’s fiscal expansionism and consolidation of social policies constituted a sharp attack on neoliberal interests.

Present-day fluctuations in the balance of forces in Latin America hint towards a revival of the Left. We need to comprehend these fluid tectonic plates of popular power from an actively political perspective. Building a socialist society in a Third World country, in which – despite its wealth of natural resources – there remains immense poverty and hideous inequality is a hard task. Moving against the powerful tide of reactionary forces and helping the oppressed classes to overcome social humiliation requires a long gestation period. In short, the entrance of the Global South subaltern on the stage of history is a richly textured pathway of socialized autonomy which never follows a linear or perfect course of economic reconstruction. Most of the times, the width of populist culture and depth of working class power intersect to generate a multi-sided trajectory of revolution. As Vladimir Lenin himself said, “Whoever expects a “pure” social revolution will never live to see it. Such a person pays lip-service to revolution without understanding what revolution is.” Thus, in the current conjuncture, we need to show solidarity with Latin America’s renascent Pink Tide which promises to deal a blow to imperialist capitalism.

This article first appeared in the Orinoco Tribune.