Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a series of articles examining the history, activity, secrets and identity of the 1% in the US. See the previous three articles here, here, and here.

Many Americans facing unemployment and home foreclosures today rightly blame the excesses of unfettered Wall Street greed. They rightly see the contribution to financial chaos made by the removal of regulations by a Congress, White House, and Supreme Court bought by corporate wealth. Most genuine liberals and pragmatic moderates in both the Democratic and Republican parties, as well as most independent progressives, in all classes, seek greater government “stimulus” spending on public works.

Such a political vision essentially seeks a return to a past system that was guided by the “priming the pump” of economics championed by New Dealers in the 1930s. Because they relied heavily on the deficit financing doctrines of British economist John Maynard Keynes, their formula for stimulating a recovery through government spending is called Keynesian economics.

Keynes was the leading proponent of using government to stimulate the economy in a downturn by balancing targeted tax cuts (tax cuts for specific types of people, such as farmers, small businesses, etc.) and public spending (public infrastructure projects such as highways, dams, rural electrification, etc.) – even, if necessary, through deficit financing, i.e., spending more than you take in as income.

Keynes, however, never advocated permanent deficit financing, contrary to claims by free marketers, nor did he advocate the permanency of debt or trade deficits. To Keynes, deficit financing was only supposed to be temporary until the economy recovered enough to sustain renewed growth. And since the U.S. had not had a trade deficit since the 1890s, he did not even factor it into his concerns about the U.S. economy during the New Deal. He, in fact, considered trade deficits one of the key impediments to recovery that the U.S. did not have to face. But getting the 1% to invest in productive industries that produced jobs and real earnings, rather than hoarding money in banks and interest-bearing financial instruments (debt) – or their favorite pastime, speculation in the sock market – was not easy.

Almost unique among advanced industrial societies, in the capitalist system in the U.S what assets and revenues the government owns are not allowed by free marketers to compete with their businesses. This gives an increasingly powerful 1% an uncompetitive “free” hand over what is profitable.

What public enterprises are profitable can be deliberately made unprofitable by restrictions on government (such as the U.S. Postal System being saddled in the last decade with annual payments to pension debts that will not come due for another 70 years, and Medicare being prohibited from competitive bargaining with Canadian distributors of American-made pharmaceutical drugs needed by the sick). These restrictions on competition with the 1% inevitably create the financial crises that then become the excuse for selling these enterprises to the 1% or eliminating them altogether. These enterprises and what is inherently unprofitable but an essential service, are left, along with the public debt, to the average taxpayer to pay for. Investment wealth is thereby controlled by the small minority who have been allowed, as incentive to private business investment, to aggregate personal wealth with few restrictions. Even though the inheritance tax on multi-millionaires (their so-called “death tax”) has been cut drastically since the incongruently prosperous 1950s, the 1% still agitates for its complete elimination.

This creates a pyramid of wealthy families right up to the wealthiest 1%. When the 1% accumulates enough wealth to control the markets and its commanding heights in banking and industry, any government under the rules of capitalism can only do two things to gain access to their wealth. Either you tax them to gain revenue and encourage them to move their money out of debt speculation into productive industries, or you borrow from them, making your debt even larger.

Under the 1%’s self-serving “trickle down” theory, the less you tax the 1%, the more incentive you give them to seek profits by investing in existing companies or setting up new ones. They see themselves, and only themselves, as the source of sustainable job growth. Most Democrats as well as Republicans, suffering from historical amnesia about successful public enterprises like publicly-owned utilities and consumer/worker/farmer-owned cooperatives in the thousands across America, accept this mantra today.

Their economic imagination is imprisoned behind the walls of ideology as rigid as that of the lords of feudalism who viewed capitalism in their day as a threat. In this year’s Republican primaries, Mitt Romney, a Wall Street raider who “saved” corporations by firing and cutting benefits for thousands of workers (amassing a $200+ million personal fortune in the process), is the living epitome of this ideology; he campaigns saying he knows how to create jobs because he is the only candidate with business experience.

But the 1% will only invest their money if they are sure their investment is safe. If you try to get them to put their money into more risky investments, you have to offer the prospect of a hefty return in profit, certainly more than what government bonds typically offer.

Any treasurer of any entity, whether a government or a business, that has to raise capital by selling bonds, notes and other financial instruments, or stock on the market, knows a basic truth of capitalism: if the entity does not eventually show a capacity—through growth in income, market share and/or equity—to pay back what it has loaned from its creditors, that entity will make its creditors increasingly nervous. The credit worthiness of your entity could be called into question, and your ability to borrow more will diminish. Governments, like businesses trying to keep up with operating expenses while paying debt, could default on their obligations and be declared bankrupt by creditors, rating agencies and courts.

It should not be a surprise, therefore, that by 1937, with the economy having shown a strong growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) since the last quarter of 1935, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., had become convinced that enough growth had occurred for him to recommend a cut in government spending to reduce the deficit, the age-old bugaboo of a Wall Street perennially worried about higher taxes on the major investor players, the upper class. His recommended cuts included public relief and works projects that employed the previously unemployed. “If not now, then when?” asked Morgentheau. Roosevelt agreed to give it a try.

At the same time, fearing an over-heated economy would trigger too steep a rise in prices (inflation) and interest rates for business loans, the Federal Reserve raised the reserve requirements of member banks to the maximum allowable under the 1935 Banking Act. This reduced commercial banks’ excess reserves and forced a $1 billion reduction in bank loans and investments just when they were needed to keep the economy moving hopefully toward a self-sustaining recovery. The New York bankers who dominated the Fed had once again miscalculated. The stock market speculation was already sopping up more and more of the 1%’s capital; putting a crunch on banks’ ability to make loans to businesses only made a bad situation worse.

The result was a disaster: a huge increase in the jobless, another huge drop in consumer spending and a commensurate drop in demand for products and services, with a drop in prices, and a return to the downward spiral of deflation. The resulting economic slowdown triggered a panic among the 1% and their flight from the stock market, resulting in a recollapse of the stock market. Roosevelt decried that the nation was suffering from the 1%’s “strike of capital.”

What had gone wrong?

First, the recovery, as critics on both the right and the left of the political spectrum had charged, had not been broad enough. It was too narrow in its effects on industries. It provided paychecks that were spent on essentials that boosted the profits of light manufacturing, entertainment and small retail businesses that served goods and services to the consumer market downstream, rather than on the products of the more capitalized (and indebted) heavy industries that were at the headwaters of almost all commodity production. This applied also to agriculture, where a small number of large farmers and agribusinesses grew while the many small farmers barely kept their farms afloat. In fact, many thousands of small farmers continued to succumb to foreclosures by financial companies like Mutual life Insurance of New York (now called MetLife), despite New Deal policies.

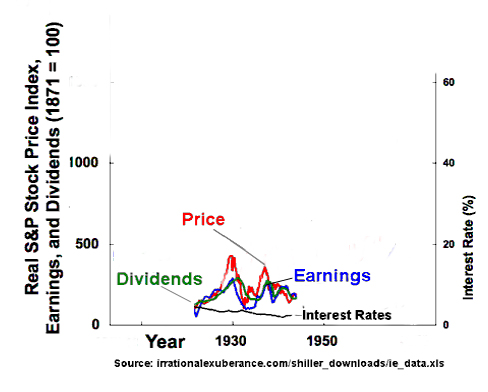

Secondly, statistics prove the contrary to free marketers’ perennial claims that the 1% would use their wealth constructively to voluntarily produce a “trickle down” of investment into productive industries. The statistical evidence shows that stock market speculation outpaced real earnings by large corporations, inflating stock prices in 1935-36 quite beyond what was justified then by corporate earnings – just as the 1% had done during the Roaring Twenties before the 1929 Wall Street crash, and just as they did to even greater degrees more before the 1987 and 2008 crashes. Below is a chart demonstrating that a resurgence of feverish gambling by the rich in the stock market, more than actual corporate earnings, was responsible for the spike in stock prices. The source is noted Noble laureate economist Joseph Siglitz:

But perhaps the most significant factor in the long term and the mostly overlooked factor was technological unemployment that had been stealthly growing since the 1920s, when output per man hour rose while unemployment persisted throughout the decade. This factor, which will be examined in subsequent columns here at Toward Freedom, was a contributing factor in the unexpected persistence and duration of the Depression of the 1930s, and remained a gnawing problem hidden in the postwar years in the ghettos through racial discrimination until its spread into suburbia in recent years.

Today’s liberals forget that Keynes’s prescription for economic growth through temporary government spending was not successful in bringing the economic self-sustained growth during the Great Depression of the 1930s for either Britain or the United States. The re-collapse of the stock market in 1937, while triggered by a cut in government spending, actually proved that four years of large stimulus spending, while commendably alleviating the suffering of working people and trying to restore the consumer market, was not sufficient to create a sustainable self-generating recovery.

That is why Roosevelt not only restored government spending in fiscal 1938, but also put greater urgency on recapturing foreign markets in Latin America from Germany, Italy and Japan, and challenging Japan’s plans to conquer the markets and resources of China and the oil fields and rubber plantations of Southeast Asia.

He brought back into his administration more conservative members of his first presidential campaign’s “brain trust,” including sugar lawyer Adolph Berle as Assistant Secretary of State for Latin America, ordering Berle to confront German and Italian aviation companies and “clear them out.” He backed these challenges with a War Mobilization Act that earmarked 30,000 industries for what would later become the military-industrial complex. He continued his buildup of the Navy’s new aircraft carrier fleet to give the Navy a longer force projection into the Pacific against Japan, and then moved the Pacific fleet from Seattle to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. In 1940, as the economy was again growing, Roosevelt campaigned for reelection on a pledge that “American boys will not have to fight in foreign lands,” a campaign for peace, even as, true to his political origins in the pre-World War I “Preparedness Movement,” he prepared for war.

By 1941, he had all but entered into a firm military alliance with Britain. He successfully persuaded Churchill, the staunch defender of the British Empire, to sign on to the Atlantic Charter’s anti-colonial “freedom principles” to rally the war-reluctant Americans, while swapping destroyers for bases in the Empire’s Caribbean and Newfoundland strategic holdings. He ordered American gunboats to fire on German warships on sight in the North Atlantic. He cut off American oil shipments vital to Japan, and ordered Secretary of State Cordell Hull to deliver a series of ultimatums to Japan on Southeast Asia and China that prompted Japanese militarists to bring down its shaky civilian government and prepare for the Japanese attack on the U.S.’s naval base at Pearl Harbor.

All of this military buildup required huge increases in government spending, and an end to New Deal expenditures. Yes, it is true that federal spending on highways and bridges, education, health care, and other civilian needs also could have primed the pump of the economy instead of spending on war materials that are wasted in war. But the fact is that such New Deal projects for the domestic economy not tied to war production did not provide the military strength needed either to defend the 1%’s overseas corporate markets and investments or to face the palpable threat of German and Japanese military conquests in Europe and Asia.

Ultimately, recovery from the Depression had to rely on U.S. military contracts and military expansion for World War II. The depressed economy of the 1930s, despite four years of the New Deal’s stimulus spending, never really gained enough momentum to sustain a recovery on its own. It required the huge mobilization of World War II to give the needed boost, along with the wartime suspension in most industries of workers’ basic right to withhold labor (to strike) when companies would not come to terms. By the end of the war, corporations and government enjoyed a closer relationship than ever before, symbolized by the War Department’s new Pentagon, the largest building in the world. In the decades ahead, presidents and Congresspeople would come and go, but the Pentagon would remain the fastest growing and most powerful force in Washington – next to the 1%’s overseas corporate economic empire it increasingly was called upon to protect.

Because of the war emergency, we will never know whether Roosevelt’s adherence to Keynes’s prescription of government stimulus spending during an economic depression, even to the point of deficit financing (borrowing as a gamble on future recovery), would have achieved sustainable recovery. The war interrupted the Keynesian experiment. After the war, despite the continuation of New Deal programs like Social Security and unemployment insurance, other global geopolitical factors, including the temporary elimination of European and Japanese corporate competition and American control of Saudi oil for collateral, allowed deficit financing in times of recession. As conservative Republican President Richard Nixon admitted, “We’re all Keynesians now.”

An unprecedented economic and political overseas empire, not Keynesian economics per se, allowed government tinkering with the postwar economy to be more successful than FDR’s efforts in the 1930s. In addition, ongoing war expenditures during the Cold War continued what World War II’s mobilization had achieved. And last, but never least, we have the giant corporate gorilla in the room, an overseas corporate empire that required –and still increasingly requires – military protection at the average American’s expense in blood and money.

But now, with Japanese and European competition back, along with the entry of China, India and Brazil as major players, and technological unemployment outpacing skilled job seekers, the Pentagon’s global reach to defend and expand the corporate empire overseas is becoming increasingly unsustainable – making for a crisis for American democracy not seen since the 1850s.

Next: Why the promised “Peace Dividend” at the end of the Cold War never happened

See previous articles:

Lessons for Obama: How FDR Fended Off The 1%’s Attacks Against His New Deal Reforms

Secrets of the 1%: FDR’s Attempt to Reform the 1%’s Wall Street

Introducing The 1% and Their Target: The Middle Class

© Gerard Colby.

Gerard Colby is the author of DuPont: Behind The Nylon Curtain (Prentice Hall, 1974), DuPont Dynasty (Lyle Stuart, 1984), and with Charlotte Dennett of THY WILL BE DONE, The Conquest of the Amazon: Nelson Rockefeller and Evangelism in the Age of Oil (HarperCollins, 2005). He has taught international economics, political science and the history of Latin American political economy at various colleges, has lectured throughout the U.S. and Brazil, and has done investigative journalism for national and local news services for over 30 years. From 2004 to 2009 he served as President of the National Writers Union, Local 1981 of the Technical, Office and Professional Division of the United Auto Workers.