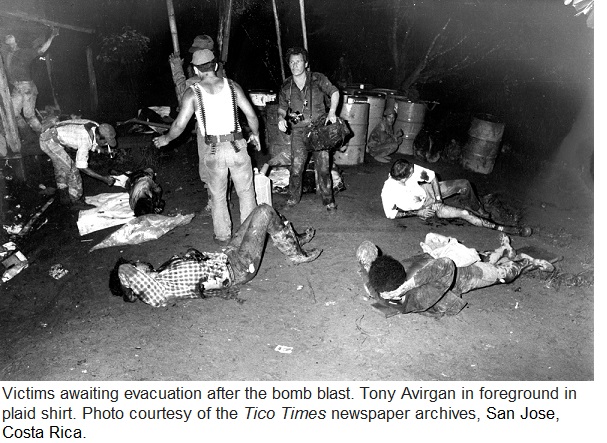

May 30th is “The National Day of the Journalist” in Costa Rica. This day was first proclaimed in 2010 by then-President Óscar Arias Sánchez (the architect of the 1987 Central American Peace Accord called Esquipulas II) to honor the dead and wounded in a bombing that took place in La Penca, just across the northern border inside Nicaragua on May 30th, 1984. Four people were killed, and more than 15 others severely wounded (some so seriously as to lose eyes or limbs) during a press conference called by guerilla leader Edén Pastora Gomez. On the anniversary of the bombing, here is a look back on what happened that day, its impact on the lives of those who were there, and the unanswered questions that remain.

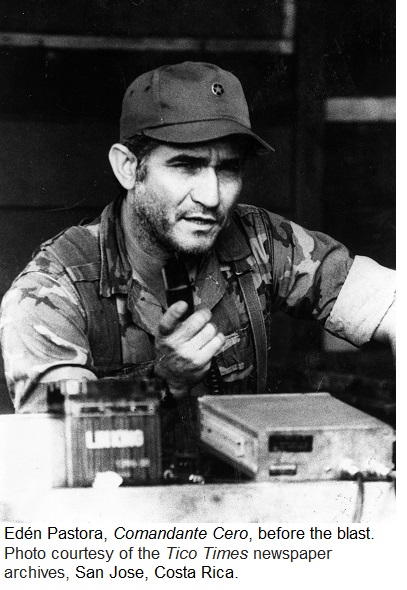

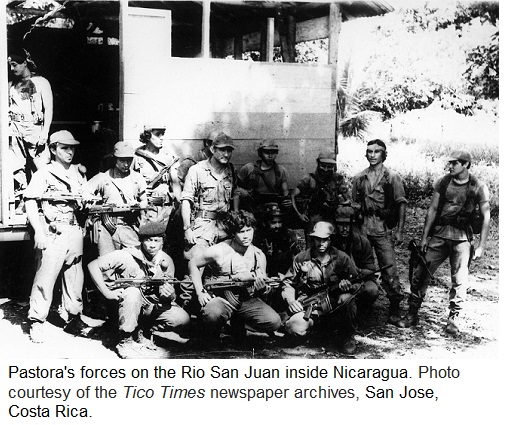

Almost immediately after the July 1979 victory of the Sandinista revolutionary forces in Nicaragua, a counter-revolution began to take shape. Initially made up mostly of former National Guard forces and those allied to the ousted Somoza government, the rebel forces began to change as some pro-Sandinista Nicaraguans became disillusioned with the direction their new government was heading. Perhaps the most prominent of these was Edén Pastora, a charismatic figure who broke from the FSLN (Sandinista Front for National Liberation) and moved to open a southern front of opposition in the jungle area along the border with northern Costa Rica. By May of 1984, Pastora was being pressured to merge with the northern Contra forces based out of Honduras. He refused and called a press conference at his jungle base in La Penca, just along the Nicaraguan border on the Rio San Juan. It was during this press conference that a bomb was detonated in an assassination attempt on Pastora’s life.

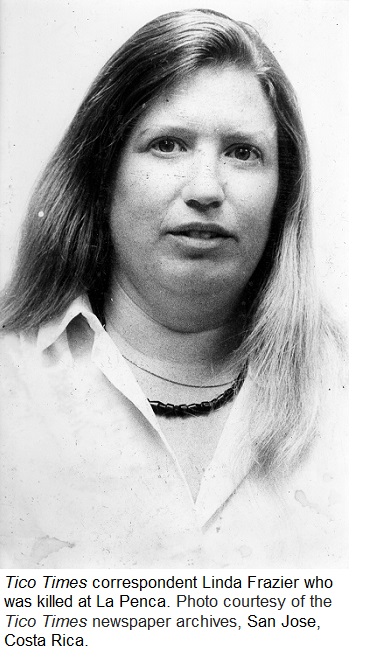

Three journalists were killed that day, Costa Ricans Jorge Quirós of cameraman for Canal 6 TV, and his assistant, Evelio Sequeira, and US reporter Linda Frazier of the Tico Times. Her husband Joe Frazier who was then Chief Central America Correspondent for the Associated Press, remembers that day: “I happened to be in [Managua] Nicaragua on other business… I’d come back from dinner…And I got to the Intercontinental Hotel, and the clerk whom known for many years, since the ‘79 revolution said ‘Señor Frazier, there’s been a…there’s been an explosion on the San Juan River. You need to know this’… And I started asking around… calling everybody I knew in Costa Rica, sort of calling in every favor I had out there, and I was getting a little panicky. And finally, I got a radio broadcast – someone had gone up live on the San Juan where the boats were coming back from La Penca, describing what was going on, and one of them said ‘well, there’s a red-head foreign lady here who’s a correspondent and she is sin vida, without life.’ And I knew then it had to be…there’s no way it was anybody else. ..I realized that in the morning I had to go back to Costa Rica and tell our ten-year-old son what had happened and that’s something I don’t wish on anybody.”

Costa Rican journalist Nelson Murillo, now retired, was a few feet away, asking Pastora a question when the bomb exploded, he said: “I ended up burnt, injured, fractured, I was two months in physical therapy in the hospital… I was left with one shorter leg, progressive deafness, PTSD and spinal problems because of the shortening of the leg. I’ve already had 30 surgeries because of problems beginning in La Penca, they took 70 shrapnel pieces out of me, metallic pieces of the bomb; since it was homemade it had everything: screws, BBs, thumb tacks, etc. It’s been a pilgrimage through the hospitals over 30 years. But there were people with amputations, Don Roberto Cruz, who died 19 years after the bombing of La Penca, lost an eye, and ear, and one leg. Out of those of us left, the present day survivors, (there were others with amputations and deformations and other serious problems that have over time died from natural causes), but of those surviving today, I am the one left with the most serious health problems.”

Costa Rican journalist Nelson Murillo, now retired, was a few feet away, asking Pastora a question when the bomb exploded, he said: “I ended up burnt, injured, fractured, I was two months in physical therapy in the hospital… I was left with one shorter leg, progressive deafness, PTSD and spinal problems because of the shortening of the leg. I’ve already had 30 surgeries because of problems beginning in La Penca, they took 70 shrapnel pieces out of me, metallic pieces of the bomb; since it was homemade it had everything: screws, BBs, thumb tacks, etc. It’s been a pilgrimage through the hospitals over 30 years. But there were people with amputations, Don Roberto Cruz, who died 19 years after the bombing of La Penca, lost an eye, and ear, and one leg. Out of those of us left, the present day survivors, (there were others with amputations and deformations and other serious problems that have over time died from natural causes), but of those surviving today, I am the one left with the most serious health problems.”

Jose Rodolfo Ibarra was injured that day as well. He is the past-President of the Association of Costa Rican Journalists: “I had 52 pieces of shrapnel in my body, in my arms, legs and chest, burns on my face and arms, plus the infection [of the wounds] that all of us who were there had.” He spent two months in a hospital recovering.

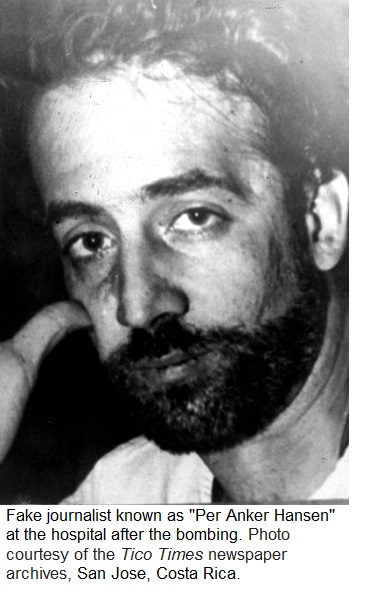

ABC cameraman Tony Avirgan remembers the long wait to get medical aid: “… the rest of us were just lined up on the ground outside and laying there, and there was only a limited number of people who could fit in the one remaining boat. And it was two hours to San Carlos, but it was a four hour round trip. So, perversely, the least injured rushed down to the boat and jumped in the boat and that boat filled up and they said that was enough and they took off. And I was laying on the ground and I was not one of the most seriously injured …but next to me was Linda Frazier and both of her legs were blown off just below the knee and she was in quite bad shape and no one made any attempt to take her or the other people. There were many Costa Ricans who lost limbs or eyes and things, and it was the least injured people who got in that first boat, including what we found out later was the bomber.”

Insurmountable Differences

Pastora, called Comandante Cero (“Commander Zero”), was leading a rebel army against the Nicaraguan government headed by Daniel Ortega. But, Stephen Kinzer, New York Times bureau chief in Managua at the time, explains Pastora had fallen out of favor with the US Central Intelligence Agency: “the CIA was eagerly recruiting people who were not tainted by collaboration with the old dictatorship. Pastora was perfect for that. He was not only untainted by collaboration with Somoza, he had led one of the greatest operations that helped bring down Somoza. So the idea that he was then going to make himself available as an anti-Sandinista fighter was thought of as a great coup for the CIA. They tried to establish him in southern Costa Rica, and at the beginning I think had very high hopes for him. The people who were the main Contra force up in the north, like [Enrique] Bermúdez, were really based in the old National Guard of General Somoza. They hated Pastora, and Pastora hated them. The idea of the CIA was: these hatreds were just details. Now we’ve got a new cause, we’re all trying to overthrow the Sandinista regime, so let’s just put behind us all the quarrels of the past. Neither side was willing to do that. And, that’s why the alliance really never gelled the way the CIA wanted to.”

Edén Pastora,who is now again working with Daniel Ortega and the current Nicaraguan government as Minister of Development of the Rio San Juan Basin, said the divisions were ideological and insurmountable: “here was a great pressure from the American Central Intelligence and right-wing sectors for me to join the north, the counterrevolution of the FDN (Nicaraguan Democratic Force), which was founded, directed, and supplied by Central Intelligence. This was impossible, for moral reasons, for political and ideological reasons. On moral terms, these guardias from the north murdered my father when I was eight years old. And when I was older, when I was 40 years old, they murdered my people in a genocide – so I could not join them for political reasons.”

Journalist Jon Lee Anderson was with Pastora’s forces a month before La Penca: “I found out, of course, eventually that he was getting money from the CIA, and, in fact, on that attack that I joined his forces on, in April of 1984, on San Juan del Norte, I discovered that he had direct CIA help. Not only had the CIA organized air-drops of logistics on certain Americans’ ranches, a network of American ranches who were sort of operating as proxies for the CIA in Costa Rica. But they had also helped shell the town from offshore, from a gunboat. And Pastora confirmed this with me. [He] begged me not to report it. I had this from several other commanders and lieutenants in the course of the battle – I really confirmed this. And this was inconvenient at the time for a lot of people, because it was only a week or so since the mining of the harbor scandal had been aired in public and supposedly put to bed…As it turned out I got in a fair bit of trouble over it within TIME magazine as a result. My biggest scoop of my young career! “

Journalist Jon Lee Anderson was with Pastora’s forces a month before La Penca: “I found out, of course, eventually that he was getting money from the CIA, and, in fact, on that attack that I joined his forces on, in April of 1984, on San Juan del Norte, I discovered that he had direct CIA help. Not only had the CIA organized air-drops of logistics on certain Americans’ ranches, a network of American ranches who were sort of operating as proxies for the CIA in Costa Rica. But they had also helped shell the town from offshore, from a gunboat. And Pastora confirmed this with me. [He] begged me not to report it. I had this from several other commanders and lieutenants in the course of the battle – I really confirmed this. And this was inconvenient at the time for a lot of people, because it was only a week or so since the mining of the harbor scandal had been aired in public and supposedly put to bed…As it turned out I got in a fair bit of trouble over it within TIME magazine as a result. My biggest scoop of my young career! “

Retired Major General John Singlaub, who was President Ronald Reagan’s administrative chief liaison to the secret Contra supply effort, in his 1991 autobiography Hazardous Duty confirms the CIA involvement early on as well: “I learned from embassy officials in Central America that the new Nicaraguan Democratic Resistance movement – the ‘Contras’ – was already in contact with the Central Intelligence Agency, and that covert American support was being organized. My old OSS case officer, Bill Casey, was now director of Central Intelligence, so I knew the resistance was in good hands.” (p.444) But Singlaub goes on to wonder if the CIA and NSC (the National Security Council, led by Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North) were making the wrong choice: “Pastora was one of those extraordinary characters who believed fervently in his own public image. He was a guerrilla par excellence, a romantic Latin warrior who evoked intense loyalty among his troops. The Agency treated him like a native mercenary. Worse, Pastora’s CIA handlers included bureaucratic bean counters who required all supply requisition forms completed in English, in triplicate. The cultural barriers between Pastora and the CIA were insurmountable. In short, the Agency ruined the only chance they had of exploiting the most famous military leader in Central America. Enrique Bermúdez was a well-educated professional soldier, but Comandante Zero was a national hero troops could rally around.” (p.485)

On May 1st, 1984, Pastora was given a 30-day ultimatum by the CIA to join forces with the FDN, so, on the 30th day, he called a press conference. “I called a press conference to denounce these issues to the world,” Pastora, now 77 remembers, “and to tell the world that I was not joining the counterrevolution, from my stance as a revolutionary, from my stance as a Sandinista. At that moment, I was a dissident, I was at odds with the National Directorate of the Sandinista National Liberation Front…So, the reason for the [press] conference, specifically, was to denounce to the people of Nicaragua and to the world, the pressure that I would not give in to or concede.”

Complex Web of Intrigue

Investigator John Mattes who worked in the Miami public defender’s office and later provided support to the Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Operations chaired by Senator John Kerry, explains that this was really part of a much larger complex operation – “…fronted by drug smugglers and con-men. And, if you boil it all down to that, that it was a mercenary adventure by elements of the Contras to sell a war to the United States so that they could engage in massive drug smuggling, and that’s really what it turned out to be…[Pastora], was a liability to everyone, he was of course a liability to the Sandinistas, and he was a liability to the Southern Front because he in fact was gonna get in the way of [Adolfo “Popo”] Chamorro and others who had their own ideas of what the Costa Rica [section of the Contra operation] should look like and what the Southern Front should look like.”

Tony Avirgan and his wife, journalist Martha Honey undertook an investigation to find the identity of the bomber. Honey, now co-founder and director of the Center for Responsible Travel based in Washington, DC, recalls “Tony was injured and was operated on in Costa Rica and then taken to a hospital in Philadelphia, and as I was preparing to go up I was contacted by the Committee to Protect Journalists and [the Newspaper Guild] and asked if I would be willing to undertake an investigation as to who was responsible for the bombing. And of course I had lots of reasons for wanting to get to the bottom of this, and so I said yes and went up and met with them and thought that this would be a couple of weeks or possibly months of investigation and we would learn what had happened, and literally until today we don’t know the full story.”

The case was later taken on by a public interest law firm known as the Christic Institute, and incorporated into their larger lawsuit against a “Secret Team” inside and outside the US government. But, Honey says, they “had a very serious falling out with Danny Sheehan, the chief lawyer there. And basically, we kind of broke with Danny and with the sort of official Christic Institute. And a group of us including Doug Vaughn and Carl Deal and Joanne Royce, who was one of the lawyers, and a number of others [including] Richard McGough kept doing the investigation, but really not so much for the Christic Institute, but simply because we were trying to get to the bottom of what was going on.”

Identifying the Bomber

The actual bomber, who had entered the press conference with a stolen passport, posing as a Danish journalist named Hansen, was ultimately identified as Argentinian Vital Roberto Gaguine through the work of investigator Doug Vaughn and others. It was Vaughn who first uncovered the fingerprint and a photo of the suspect in Panamanian immigration files: “Eventually I was able to obtain from Panamanian immigration records, fingerprints and photographs of Gaguine when he appeared as Per Anker Hansen and used the Danish passport in Panama before the attack at La Penca in 1984…, I was [later] able to locate the family of Gaguine in the Miami area. His father, in 1992, identified a photo of Gaguine to me as his son, Roberto, as he was called, and the brother also identified the photo, and they also identified several of the photos that were taken before and after La Penca in Costa Rica as having been their brother, who they were convinced, even then, could not possibly have done the bombing, but that he was actually someone who was fighting for freedom, socialism and democracy…”

The actual bomber, who had entered the press conference with a stolen passport, posing as a Danish journalist named Hansen, was ultimately identified as Argentinian Vital Roberto Gaguine through the work of investigator Doug Vaughn and others. It was Vaughn who first uncovered the fingerprint and a photo of the suspect in Panamanian immigration files: “Eventually I was able to obtain from Panamanian immigration records, fingerprints and photographs of Gaguine when he appeared as Per Anker Hansen and used the Danish passport in Panama before the attack at La Penca in 1984…, I was [later] able to locate the family of Gaguine in the Miami area. His father, in 1992, identified a photo of Gaguine to me as his son, Roberto, as he was called, and the brother also identified the photo, and they also identified several of the photos that were taken before and after La Penca in Costa Rica as having been their brother, who they were convinced, even then, could not possibly have done the bombing, but that he was actually someone who was fighting for freedom, socialism and democracy…”

Vaughn initially worked with Avirgan and Honey and the Christic Institute, and later provided material to Juan Tamayo of the Miami Herald, who first published the identification of Gaguine in August 1993. Tamayo, a close friend of Joe and the late Linda Frazier, said he felt obligated to try to find the perpetrators: “when she died at the La Penca bombing, I always thought that, you know, we all had a responsibility as journalists to solve the murder of a fellow journalist. It was a personal interest and so for many years every chance I had I sort of asked people ‘do you know anything about this?’ You know, anybody I thought might know something about the case.”

It was eventually determined that Gaguine had died in 1989 in a failed assault on La Tablada barracks in Argentina, but because no firm evidence of his death was found, an Interpol warrant for his arrest remained open until last Fall. Then, on November 15th, 2013, Argentine authorities told Costa Rican officials that DNA evidence from the bones held by his family confirmed Gaguine’s death. On December 2nd, Costa Rican , Attorney General Jorge Chavarría Guzmán gave press conference saying the case would be closed because there was no new information available. But, Chavarría (who had investigated the case as a prosecutor in 1989 resulting in a 180-page report to the Costa Rican Legislative Assembly) said in the press conference that while the investigation is closed in Costa Rica as there is no information or clues about the masterminds of the attack, if any other country like Nicaragua has new information, the case in Costa Rica could be reopened, since it has been classified as a crime against humanity, which has no time limit.

Trying to Identify the Intellectual Authors of the Plot

Peter Torbiörnsson was a Swedish journalist who now admits he was also spying for the Sandinistas in 1984. He regularly gave copies of his footage to Nicaraguan intelligence services under the direction of Comandante Tomás Borge. It was Torbiörnsson who brought the fake journalist Per Anker Hansen to the press conference that day. He recently produced an introspective 90-minute film, full of personal agony, called “The Last Chapter, Goodbye Nicaragua” released in festivals in 2010 and first shown in Costa Rica and Nicaragua in 2011. The film also features British journalist Susie Morgan, who was seriously wounded at La Penca. Morgan has sought to solve the crime for the past three decades and made her own investigative film for British television in 1988 and authored an autobiographical account of the investigation entitled In Search of the Assassin. Morgan was standing right next to Pastora when the explosion took place and feels it was her body that actually shielded him from some of the from the worst effects of the blast.

Edén Pastora, whose legs were injured by the explosion and spent weeks in a hospital in Venezuela recuperating after plastic surgery, blames Torbiörnsson for his role in the attack: “It was people such as Torbiörnsson, who did the reconnaissance; he spent 15 days with me and brought the information to the Sandinistas and to the CIA, because he was a double agent. As was the fake journalist Per Anker Hansen, whose real name was Roberto Vital Gaguine. They were crazy people, who liked to experience intense thrills, working with the left and with the right. They were double agents, Roberto Vital Gaguine died at La Tablada during the assault to the headquarters of the Carapintadas in Buenos Aires, and Torbiörnsson is still playing his role as a double agent; sent by Central Intelligence to misinform the people, feigning outrage and accusing the Frente [Sandinista National Liberation Front] directly. The truth is the Frente gave the order to place the bomb, but at a camp. They gave the order to place the bomb under a hammock, since that was what Torbiörnsson had recommended, not at a press conference. It was a decision by Torbiörnsson and Roberto Vital Gaguine to place it at La Penca, because they had not been able to hunt me down for three months. I hadn’t given them the opportunity to do it at a camp or the other places where I camped. People don’t know these things about these double agents Torbiörnsson and Roberto Vital Gaguine.”

Pastora has suggested that Torbiörnsson, now 73, should be officially accused of crimes committed against humanity for his role in facilitating the plot. Torbiörnsson responded that “…Edén Pastora has gotten the supervision of Rio San Juan in compensation for his effort to transform himself into a mouthpiece for his former enemies…He has forgotten his moral obligation to the other victims, the right to know the truth…”

La Penca’s Personal Impact

Jon Lee Anderson notes that “the Pastora hit was maybe the first of its type of assassination in which explosives were used under cover of journalists. Everything has changed since then. It was shocking to us and it was dangerous. Of course it made our lives very dangerous. It suddenly thrust all of us… It made us feel that we couldn’t trust people in quite the same way and made everybody wonder where we stood…who were the people that we were dealing with, both in regimes and in these insurgent movements, and the people that travelled in those circles.”

Juan Tamayo concurs: “We’ve always been sort of concerned about intelligence services passing themselves off as journalists. We find that to be objectionable because it puts real journalists at risk. You know, any number of journalists can then get arrested because some government thinks that they are spies or something. So not only does the killer pass himself off as a journalist, but he then sets off the bomb in a news conference. I don’t think it could have been any worse. That was a blot on journalism.”

Juan Tamayo concurs: “We’ve always been sort of concerned about intelligence services passing themselves off as journalists. We find that to be objectionable because it puts real journalists at risk. You know, any number of journalists can then get arrested because some government thinks that they are spies or something. So not only does the killer pass himself off as a journalist, but he then sets off the bomb in a news conference. I don’t think it could have been any worse. That was a blot on journalism.”

Joe Frazier knew his work was dangerous, but the bombing at La Penca was totally unexpected: “I think we all just sort of realized that it was sort of a risky shot out there, and you do your best to be careful and there are some things you can’t avoid. Now, who would have known, or who would have thought that somebody would have bombed, of all things, a press conference. They might as well bomb a church.”

Stephen Kinzer, who had only missed going to the press conference by chance recalls, “I was in total shock. My first reaction was that my friends had been attacked. One of the women who was a victim of that attack, Susan Morgan, lived in Managua and I used to see her every other day. Linda Frazier was a real bedrock of the press corps in Costa Rica. Several of those other people present were people that I worked with all the time. We had never had an episode like this before. And then after I recovered from my shock at realizing what had happened to my colleagues it dawned on me that it could easily have been me. Just by a trick of fate I didn’t happen to be there, but this was a stunning episode far beyond anything that we had anticipated. ….I don’t think it changed our minds about anything, but it intensified our feeling that we were in a deeply unpredictable and highly violent situation. It really showed that we didn’t have a full grasp of the possibilities of what might happen, and that is always unsettling.”

Jose Rodolfo Ibarra sees the event as a turning point: “Journalism in Costa Rica can be depicted in a very clear before and after phase. Before La Penca, we did not worry much about security because we were not accustomed to those sorts of violent acts. One would enter any press conference, any place where there would be information, without noticing your own surroundings. From that point on the people understood, first that security measures were necessary, and second that journalists are not immune, we are not superman.”

Lack of Resolution and the Search for Truth

Nelson Murillo feels that this type of thing needs to be denounced: “It is a thorn stuck in the [journalist’s] guild, and that the impunity could have lasted thirty years is a national and international embarrassment. Only two press conferences have been used for purposes of terrorism, one in Afghanistan [the murder of Ahmad Shah Massoud in 2001], and the one of La Penca in Nicaragua. And so the bombing of La Penca is a case of deception in all ways that deserves more attention, more pressure; that deserves more opportune answers, that deserves more constancy in the media.”

The memories still affect them even today said Joe Frazier, “for the first few months after that, that entire summer is almost a total blank in my mind. I don’t remember anything really. I don’t remember where I was, what I did, whom I talked. I know I was in New York for a while, I know I was back in Oregon for a while. I couldn’t…I couldn’t function… .I was a wreck for some time..”. He says the pain of the loss is still with him today, after thirty years.

Murillo is now one of the lead activists on seeking justice for the victims of La Penca. “Especially after the death of Don Roberto Cruz who fought long to find the truth of these things and fought against the scandalous impunity of the case, in time I began to turn into an activist for this cause, because the only hope for justice that is left to us is an international trial through the Inter American Court of Human Rights where there is a denunciation presented by the Association of Journalists in August of 2005 when case of La Penca already had 21 years of impunity. Now it has been 30 years, more than 8 years of waiting and the denouncement is still being processed through to admission, they have not yet said yes or no officially.”

Will there be a resolution? Investigator John Mattes wonders: “I would hope so for [the victims] peace of mind. Sadly, though, I look back over that period…we lost a number of whistle blowers. We lost people that tried to stand up, and that were lost in the night. So we won’t know everything though I think, and in much to their credit, and to the people that did stand up, we now know the truth. We may not know the details, but we know the truth. And we know what the United States did in this failed operation.”

Attorney Chavarría, in his 1989 report to the Costa Rican Legislative Assembly, concluded with this statement: “To finalize, this report does not put an end to the investigation of the crime of La Penca, which should continue in the clarification of the events. A great deal of useful information is in the United States, and it will depend on the good faith of the authorities of that country to give access to what has been censored in the Senate reports. In the same way, without the help of those authorities it will be impossible to interview witnesses in that country, for which reason I consider it important that the respective steps be carried out by the Government Attorney and the Plenary Court.”

Now that three decades have passed since the bombing, and many of the witnesses and participants are no longer alive, a resolution seems difficult. Somewhat presciently, on the day after the bombing, Mike Boettcher of NBC News reported: “The blast occurred in a no-man’s land along a river that separates Nicaragua and Costa Rica. There is no law there. So it will nearly be impossible to determine who planted the bomb and why.”

Juan Tamayo echoes this thought today: “The other thing is the crime took place in Nicaragua. The Costa Ricans have sort of become involved in it because many of the victims were Costa Ricans, but the crime, the bombing actually took place in Nicaragua, so, is the Nicaraguan government, now under former Sandinista President Daniel Ortega, willing to dig up this old history? I doubt it very much.”

Tony Avirgan holds out some hope “Well, I keep having the…the hope that someday, the…you know, somebody on the US side and somebody on the Sandinista side will come forward and we’ll just find all the answers, but I’m not sure that digging anymore is gonna help. And we mentioned before, you mentioned before, a lot of the people are dying now. People are getting old and dying, so…” but, Martha Honey continued, “ I think that there’s still room for a real investigation of it and it should probably be done by people who were not like us, who were not involved, but would draw on a lot of the work that’s been done and just try to make sense of this because we don’t know the truth. We don’t know the full truth.”

Costa Rican journalist Nelson Murillo insists a resolution is necessary: “Although the mercenary that detonated the bomb is dead, and registered as such in Argentina, the responsibility of the intellectual author is another thing that is still in force, and is a goal which we must investigate deeply and inform and denounce all that appears in time.”

For Jose Rodolfo Ibarra it is important to keep the memory of La Penca alive: “I would hope that this 30th of May, the thirtieth anniversary that act, that the new generation of journalists do not forget what happened there. We have to learn from what happened there. May they not forget the dead and the injured. It’s necessary to be aware of what happened there so that it does not happen again.”

Doug Vaughn concluded by saying, “you have to do it by telling the truth. Let the chips fall [where they may].”

*

For more information and to get involved with the search for truth around the La Penca bombing, visit the Costa Rican Journalists Association.

*

Norman Stockwell is a freelance journalist based in Madison, Wisconsin. He also serves as Operations Coordinator for WORT-FM Community Radio. Stockwell has reported from numerous countries in Latin America, including interviews on Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast with Contras surrendering to take amnesty under the 1987 Esquipulas Accords. Sarah Blaskey and Jesse Chapman in Costa Rica contributed reporting to this article.