Burlington, Vermont – Sometimes, but not always, increased oppression begets increased resistance. In almost all cases, however, resistance is the hallmark of humanity’s long struggle for freedom from tyranny; in fact, it is the indispensable groundwork of freedom’s victories.

Today, the founding principle of religious freedom in America is being challenged by a federal government ordering federal agents to bar entry into the United States of immigrants of the Islamic faith, one of the largest religions in the world. Many of these immigrants are refugees from tyranny, wars’ poverty and widespread criminal breakdown of law and order.

People who have been living here peacefully for decades are suddenly being seized by federal agents and local police off the streets, in their homes, their workplaces, their schools, their community centers, even their places of worship. Children are being torn from their parents’ arms and must watch, bewildered, as their parents are being led away and stuffed into police vans and caged patrol cars and driven to detention centers behind walls, bars and barbed wire.

There are few people left in today’s America whose memories can recognize these desperate flights from such atrocities as resembling what happened in the 1930’s in Italy, Spain and Germany. But these abuses are happening here, today, in the United States of America, in our vaunted land of the free and home of the brave.

The perpetrators are not those being arrested. The perpetrators are those who order the violation of human rights of the families and individuals whose greatest crime is their willingness to risk their lives and arrest to reach a free land where they can see their sons and daughters become American citizens.

These “non-citizens” have forebears in our country’s proud history, in the story of the Underground Railroad before our Civil War. Then, too, people who were legally not citizens strove for freedom and citizenship. For them, the U.S. Supreme Court was an instrument of tyranny led by a Chief Justice, Roger Tawney, who represented the most conservative and politically powerful forces in our country. In the landmark case in 1857 of Dred Scott, a runaway slave who had been recaptured in the North but claimed his seizure violated his constitutional rights as a citizen, it was the slaveholders, including Tawney himself, who prevailed upon the Court to uphold federal law, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, and deny African-Americans, whether slave or free, the right to citizenship or freedom anywhere in the United States, even in states and territories where slavery had been prohibited by state law. Moreover, under the Fugitive Slave Act, federal marshals and local sheriffs and police in the North were ordered to assist slaveholders in this legal kidnapping.

These legal oppressions should have been crushing blows for the abolitionist movement, but they were not. Instead, the federal outrages swayed many Northerners against slavery as a legal institution and against the Southern slaveholders who profited from it, and, of course, defended it. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, greatly expanding federal power to protect the property rights of slaveholders and requiring the North to become involved in enforcing the federal law against harboring fugitive slaves. As a result, antislavery organizations grew. So did the clandestine networks moving fugitive slaves north which later became more widely known as the Underground Railroad.

Up to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, the Underground Railroad’s networks were operated mostly by fugitive African-American slaves and those who had earned or bought their legal freedom. It had been functioning and growing since before the Revolution, when kidnapped Africans’ status as somewhat of an indentured servant deteriorated to lifelong servitude during the 17th century. The American colonies’ economic growth depended increasingly on obtaining a cheap labor supply, resulting in racial legal codes by the 1680’s to justify slavery. Within a century slaves in large numbers had reached the Dutch estates along the Hudson River and their English successors in New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania. Crispus Attucks, the first African-American killed by the British during the 1770 Boston massacre, was a runaway slave. George Washington, who owned thousands of slaves and may have been the richest American of his time, complained in 1786 about the difficulty of recapturing one of his runaway slaves in Pennsylvania “where it is not easy to apprehend them because there are a great number who would rather facilitate their escape…than apprehend the runaway.”

A year later, in 1787, with Washington presiding, continental delegates in Philadelphia, in secret session, arbitrarily scrapped the Articles of Confederation. In its place they adopted the Virginia Plan authored by James Madison for drafting a new national Constitution. The Constitution recognized slaves as people each worth three-fifths of a human being for the purpose of counting a state’s population in the national census every ten years to give the South greater proportional representation in the new House of Representatives. At the same time, it recognized slaves as the legal property of slaveholders like Washington, Jefferson, and Madison (the celebrated “Father of the Constitution”). In Article 4, Section 2 it stated that “No person held to service or labor in one State, escaping into another, shall in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.”

In the North, where seasonal changes required differential work and allowed for the rise of valued crafts among African-Americans in the cities, the whites had more difficulty squaring the Declaration of Independence’s ideals with the brutality of slavery. Without much economic incentive to retain it, states in the North abolished slavery before the centralized government had been established under Washington’s presidency in 1789. But in the South, the long warm seasons were conducive to extensive plantations using masses of slaves for growing, curing, and exporting tobacco. After the invention of the cotton gin to easily separate cotton from its seeds, cotton became King Cotton for export to Europe to pay off debts and support a luxurious living for the white slaveholders. Slavery took deep root, and most slaves could only look north in their yearning for freedom.

There were revolts, of course, just as there had been 300 documented slave mutinies during the South Atlantic “middle passage” from Africa that even when “peaceful” took the lives of 20% of the men, women and children typically packed like sardines into the ships’ holds. But the fear of slave revolts among slaveholders like Jefferson and James Monroe was more documented in surviving letters and newspapers than the extreme cruelty employed by slaveholders in putting down slave uprisings. Even the recording of runaways and slave revolts undermined the slaveholder’s cherished claim of the contented slave and humanitarian owner. Some slaveholders’ fears reflected realities too evident to be ignored by newspapers, such as conspiracies by the slaves Gabriel (1800, Virginia) and Denmark Vesey (1822, South Carolina), and there was always a fear of a replication of slaves returning white violence in revolts such as Nat Turner’s (1831, Virginia).

Then there were the slaveholders’ fear of foreign lands (such as black-ruled Santo Domingo in the Caribbean) aiding slave revolts in the South, and the fear of neighboring Mexico, which outlawed slavery, providing a haven for runaways such as Spain’s northern Florida had become. Both the Spanish Florida and Mexican (Texas) threats were crushed by slaveholders-inspired American revolts and annexation in the U.S. Thus, the attempt to resolve the social and political contradictions within the United States without getting to the root of one of the problems—slavery—led to further U.S. violent land grabs and slavery’s expansion.

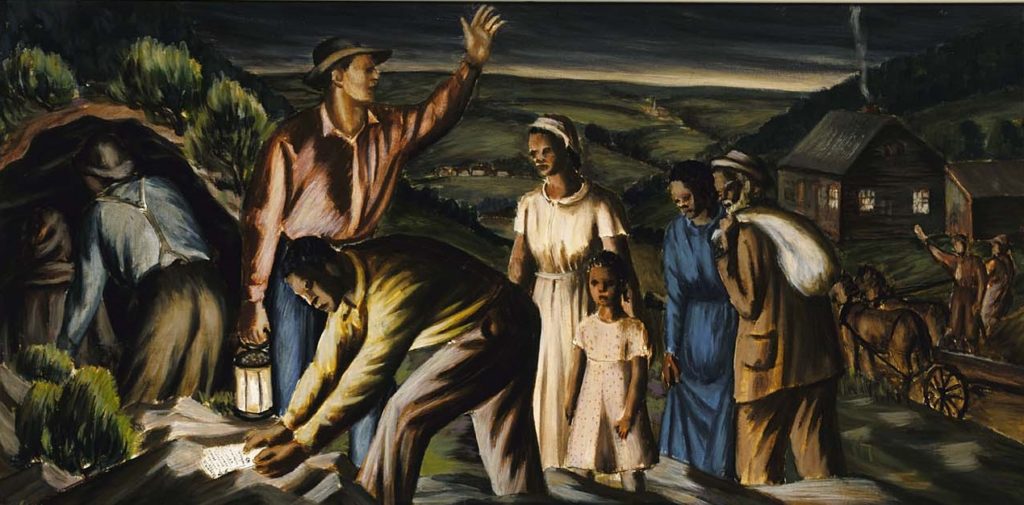

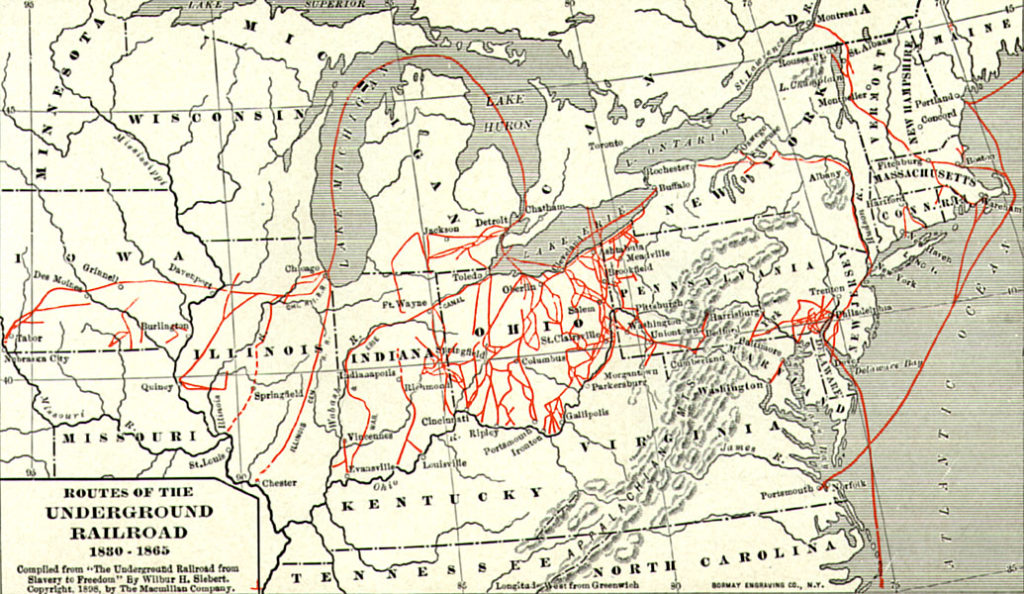

Under these conditions it should not be a surprise that free African-Americans should increase and interconnect their networks of escape to the North from the 1830’s on. The Underground Railroad’s major escape routes were from Maryland through Pennsylvania to New York and New England and from Kentucky and Virginia into Ohio. Along the way, fugitive slaves were given shelter, food, medicine, and clothes. These networks were assisted by local Committees of Vigilance, groups of blacks and whites that provided vital information on runaways and alerts against slavecatchers operating in the North, and rescues of seized refuge slaves.

The support given slavecatchers by federal marshals and local courts and police did not deter these committees from carrying out their pledged duties to warn the “conductors” of the Underground Railroad and the “station masters” who provided temporary safehouses and hiding places. The work of the Underground Railroad was dangerous, possibly leading to federal arrest, prosecution and imprisonment. Nor were local anti-slavery leaders funding or otherwise supporting networks unknown. But the sheer size of the anti-slavery movement gave shelter in numbers. Despite unfounded accusations in the South that his anti-slavery writings had inspired the bloodied Turner rebellion, the prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison remained undaunted. The following year, in 1832, he and others founded the New England’s Anti-Slavery Society. Within five years the organization had grown into 1,350 chapters. In 1833 the American Anti-Slavery Society was founded under the leadership of Garrison and three African-Americans, Rev. Samuel Cornish, Rev. Theodore S. Wright and Robert Purvis, son-in-law of wealthy African-American Philadelphia sail-maker James Forten, who became the Society’s vice president and was the major funder of Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator. By 1838, this organization had some 250,000 members. That year the cause of abolition gained perhaps its most eloquent spokesman when an escaped slave named Frederick Douglass fled Maryland, reached Massachusetts and then moved to Rochester, New York to start a weekly newspaper the North Star, aptly named after the guiding light of the estimated 100,000 people who fled north on the Underground Railroad.

Outside Cincinnati, Quakers Levi and Catherine Coffin regularly welcomed groups heading north, inspiring Harriet Beecher Stowe to base the fictional Holidays on them in her 1852 book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the most influential and popular abolitionist novel before the Civil War.

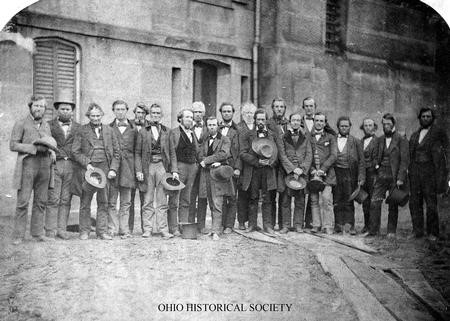

Ohio, across the river from slave-holding Kentucky, hosted one of the most active networks of the Railroad. Backed by a large free black population, the Quaker Fellowship, and Oberlin college’s many abolitionists, the Underground Railroad there spirited fugitive slaves across the river and even rescued fugitive slave John Price from arrest by a U.S. deputy marshal who came to Oberlin town. Forty local residents took part in the 1858 rescue, and the 37 were subsequently indicted and 20 jailed, but only two were convicted by trial. Meanwhile, Ohio State authorities arrested the federal marshal, his deputies, and other men involved in Jon Price’s seizure. Finally, in 1859 an agreement was reached to release the federal marshal and his men without being charged with a crime if the remaining 35 rescuers were immediately released. They were. The Oberlin station, rather than being crushed, grew in strength from the struggle.

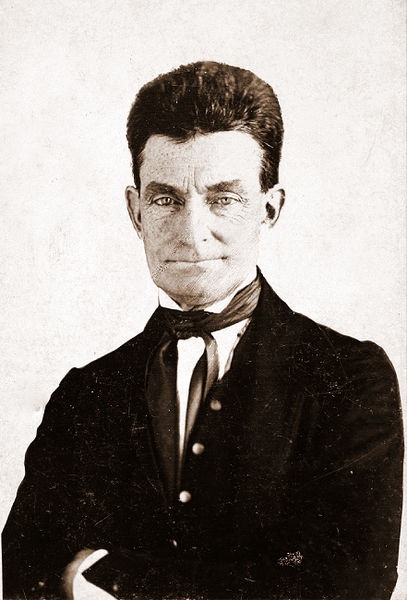

Meanwhile, abolitionist Moses Dickson, founder of the Knights of Liberty and a leader of a secret underground network claiming to have 200,000 slaves in the South ready for armed rebellion, had been convinced that a civil war was approaching and tried to persuade John Brown to hold off on the planned attack on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Dickson failed, but Brown had also failed to convince Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman to join him.

Brown, fearing to lose momentum, attacked anyway in October 1859, hoping to spark a slave rebellion using the nearby Appalachian mountain chain into the South as a base of operations as planned. Brown sent some of his 16 men to seize Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington, at his slave-holding Beall-Air estate while he took the giant federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry by surprise. Washington and his associates arrived as hostages at the Harpers Ferry Arsenal along with three of Washington’s slaves. But Brown soon was engaged in a firefight with local militia and was forced back into the arsenal’s firehouse. He was then surrounded by federal Marines led by Col. Robert E. Lee, Lt. J.E.B. Stuart and First Lt. Israel Greene. One of Brown’s sons was shot carrying a white flag attempting to negotiate a surrender and his other son had been mortally wounded. Brown refused to surrender to Lee’s demand. The Marines then charged and shot their way into the firehouse. Identified by Col. Washington, Greene immediately brought his saber down to behead Brown but cut the back of his neck instead. As Brown fell with a gun in his hand, Greene thrust another stab into Brown’s chest, but the blow was deflected by the scabbard buckle of the sword Brown was wearing. Brown’s life was saved, ironically, by the sword allegedly presented to George Washington by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick the Great and taken from Beall-Air by Brown’s raiders to bring to Brown as a trophy.

Denied a federal trial, Brown was found guilty of treason to the Commonwealth of Virginia and hanged in December, his death satisfactorily witnessed by Southern actor John Wilkes Booth, the future assassin of President Abraham Lincoln. But four raiders escaped and were given refuge by the Underground Railroad, three of them later serving in the Union army while Col. Washington fought for the breakaway Confederacy along with Generals Lee and Stuart. Predictably condemned in the South and much of the North as a “madman,” John Brown emerged as a martyr for many abolitionists in the North who now believed Brown was right to prophesize in his last testament that slavery could be ended and the nation saved from Southern separatists only by bloodshed.

By the following spring of 1860 the South was facing slave rebellions and unrest and the North was seething with abolitionist enthusiasm. The new Republican Party, founded in 1854 and energetically supported by abolitionists, nominated for President a former Illinois Congressman by the name of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln had protested the war against Mexico as an extension of slavery and as a result had lost his effort at reelection. He had denounced the Dred Scott decision in a speech in 1857 that also pointed out the impracticality of asking slaveholders to pay for colonization in Africa. “A house divided cannot stand,” Lincoln had stated during debates against Illinois’s Democratic U.S. Sen. Stephen Douglas in 1858, earning log-cabin-born Lincoln a favorable reputation as “Honest Abe” in the North. But many Southern leaders knew of Lincoln in a different light, as the smart lawyer who successfully had defended the Illinois Central Railroad’s right to cross the Mississippi, ending forever the river’s and the South’s domination of trade with Ohio and the rest of the Midwest. The Southern plantations were increasingly replaced by the more lucrative trade with Northeast cities as the Midwest farmers’ major market and source of capital. With this commercial change went the South’s chief political ally in Congress. This was the new geopolitical realignment of the 1850’s that propelled the rise of the new third party that, with the North–South split in the Democratic Party, assured the election in 1860 of Abraham Lincoln.

The South rebelled the following spring of 1861, but throughout the Civil War the Underground Railroad continued its work. Harriet Tubman returned from Canada to work as a Union Army nurse, scout, and spy. By then Union soldiers were singing “John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in his grave but his truth goes marching on” as they took up Lincoln’s call to arms to defeat the leader of the slaveholders’ Confederate Army. Gen. Robert E. Lee. Lee’s plantation across the Potomac River from Lincoln’s Washington D.C. was seized by federal troops, its slaves freed, and his estate turned into a hospital for wounded soldiers. Ironically, it was converted into a village and center for African-American freedman before it became the first national cemetery for veterans and their families—including African-Americans who had served in the Union Army and were buried beneath tombstones that bore each name and the simple but cherished word: Citizen.

With the war and African-Americans’ citizenship won, the Underground Railroad’s work continued during the Reconstruction in the struggle to protect the emancipation from Jim Crow laws until 1876-7 when a political deal was struck during the presidential elections and federal troops were withdrawn from the South to fight Native American tribes in the West and Southwest, and striking railway workers in the North. But the Underground Railroad’s daring work before and during the Civil War became the stuff of legend, enshrined as one of the world’s most powerful embodiments of human courage and freedom.

Today, as federal agents hunt for undocumented immigrants, breaking up families who have lived here for many years, many Americans are remembering the political efficacy and moral power of the Underground Railroad. It is time to put its lessons again into practice.

Gerard Colby is the former President of the National Writers Union/UAW Local 1981. His work has been published by national news outlets such as The Los Angeles Times, the North American News Agency/United Features, The Nation, In These Times, The American Writer, and Toward Freedom. He is the author of Du Pont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain (Prentice Hall, 1974, Lyle Stuart Inc, 1984 and an updated 2016 e-book edition at Open Road’s Forbidden Bookshelf. A recently updated e-book edition of Colby’s and Charlotte Dennett’s Thy Will Be Done, The Conquest of the Amazon: Nelson Rockefeller and Evangelism in the Age of Oil is also scheduled to be released soon by Open Road. He currently serves on the editorial committee of Toward Freedom’s board and on the board of the Henry Demarest Lloyd Fund for Investigative Journalism.