Editor’s Note: This opinion was published as “Left-Right White Solidarity?” in Common Dreams in 2014, shortly after the U.S.-backed neo-Nazi coup in Ukraine, in response to solidarity emerging between left-wing and right-wing people of European descent in the United States and in Europe. However, this does not refer to the “horseshoe theory,” a concept that suggests the left and the right have much in common and pose a threat to a so-called “center.” The horseshoe theory leaves out the colonial question: What happens to people who have been colonized by Europeans in the United States and around the world? And what impact does white supremacy have not just on those who have been colonized, but on people of European descent? This version has been edited with the author’s permission.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” -George Santayana

Some years ago, Italian anarchist Camillo Berneri suggested that while not always visible in the social practices of everyday European life, the racist foundation for European fascism was still present, safely confined to a space in the European psyche, but always ready to explode in what he called a “racist delirium.”

Today, white workers and the middle classes in Europe and in the United States, traumatized by the new realities imposed on them by the decline of the Western imperialist project and the turn to neoliberalism, are increasingly embracing a retrograde form of white supremacist politics.

This dangerous political phenomenon is developing in countries throughout the European Union and in the United States. Just recently, the National Front, a racist, authoritarian party that labored on the fringes of French politics for years, has emerged as one of the dominant forces. The Tea Party in the United States, Golden Dawn in Greece, the People’s Party in Spain, the Partij Voor de Vrijheid in the Netherlands—in these and other countries, a transatlantic, radical racist movement is emerging and gaining respectability.

The hard turn to the right is not a surprise for those of us who have a clear-eyed view of Euro-American history and politics. In all of the 20th century fascist movements in Europe, two elements combined to express the fascist project: 1) The rise of far-right parties and movements as the political expression of an alliance of authoritarian, pro-capitalist class forces bankrolled by sections of the capitalist class and constructed in the midst of capitalist crisis; and 2) racism grounded in white supremacist ideology.

The neo-fascism that is now emerging within the context of the current capitalist crisis on both sides of the Atlantic has similar characteristics to the movements of the 1930s, but with one distinguishing feature. The targets for racist scapegoating are different. The targets today are immigrants: Arab, Muslim and African in Europe; and Latinos as well as the never-ending target of poor and working-class African Americans in the United States.

What makes the rise of the racist radical right even more dangerous today is that it is taking place in a political environment in which traditional anti-racist oppositional forces have not recognized the danger of this phenomenon or—for strategic reasons—have decided to downplay the issue. That strategy has been tragically played out in the “immigrant rights” movement in the United States.

The brutal repression and dehumanization witnessed across Europe in the 1930s has not found generalized expression in the United States and Europe, at least not yet. Nevertheless, large sectors of the U.S. and European left appear to be unable to recognize that the U.S./NATO/EU axis that is committed to maintaining the hegemony of Western capital is resulting in dangerous collaborations with rightist forces both inside and outside of governments.

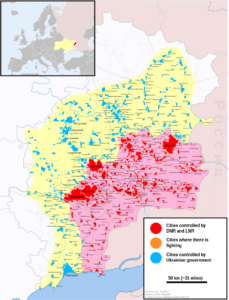

The manufactured crisis with Russia over the issue of Ukraine is a case in point. The incredible recklessness and outrageous opportunism of the U.S./NATO/EU axis in destabilizing Ukraine—knowing that the driving forces on the ground were racist, neo-Nazi elements from the Right Sector and the Svoboda party—demonstrated once again the lengths this axis is prepare to go to achieve its geo-strategic objective of full-spectrum economic and political global domination.

Yet, strangely, not only did many radicals in the United States and Europe not see the potential threat this situation represented—they seemed unable to penetrate the simplistic cold-war propaganda that suddenly re-emerged to frame events in Ukraine.

Instead of being concerned that—as a direct consequence of U.S. actions—a government came to power in Europe that, for the first time since the 1930s, included ultra-nationalist, racist neo-Nazis in key positions, the left along with the general population allowed the corporate media and U.S. propagandists to turn the narrative away from U.S./EU destabilization of Ukraine to Putin’s supposed expansionist aspirations.

The ease in which the corporate media was able to flip that script and make Putin the new face of evil has been truly astonishing. And the fact that that narrative was embraced by most liberals and large sectors of the white left in the United States only affirmed that—having abandoned class analysis and anti-imperialism, and never really having understood the insidious nature of white supremacist ideology—the U.S. left has no theoretical framework for apprehending the complexities of the current period.

The inability to extricate itself from the influences of white supremacist ideology has to be considered one explanation for the strange positions taken by large sectors of the white liberal/left over the last few years. How else can one explain the bizarre incorporation of the discourse of “humanitarian intervention” and the obscenely obvious racism of the “responsibility to protect”?

Could it be that many white radicals have fallen prey to the subtle and not-so-subtle racial appeal to a form of cross-class white solidarity in defense of “Western values,” civilization and the prerogative to determine who has the right to national sovereignty, all of which are at the base of the rationalization of the “responsibility to protect” asserted by the white West?

The apparent incapacity of white leftists to penetrate and understand the cultural and ideological impact of white supremacy and its powerful effect on their own consciousness has weakened and deformed left analysis of U.S. and European foreign policy initiatives. It has also resulted in the U.S. and European left taking political positions that either objectively championed U.S./NATO imperialist aggression or provided tacit support for that aggression though silence.

As a consequence of the abandonment of anti-imperialism and an active class-racial collaboration with the Western bourgeoisie, an almost insurmountable chasm has been created separating the Western left from its counterparts in much of the global South.

Instead of more resolute anti-imperialist solidarity, broad elements of the white left in the United States and Europe have consistently aligned themselves with the policies of the U.S/NATO/EU axis that supports right-wing forces from Ukraine to Venezuela.

Exaggeration, racial paranoia, and an overly simplistic and divisive—even “racist”—assessment of the liberal/left will be the charge. We accept those charges. We accept them because we know they will come. For those of us living outside the walls of privilege who must nevertheless accept the realities of the colonialist/imperialist-created global South, we don’t have the luxury of comforting illusions. Our lived experiences negate the false history of Europe’s benevolent civilization. We see developing in Europe and in the United States the very real possibility of a left-right racial convergence fueled by crisis, leftist ideological confusion and what appears to be a mutual commitment to maintaining the global structures of white supremacy.

Understanding the violent history of the Western project and the pathological nature of white supremacy, we are forced to see with crystal clarity that within the context of the volatile economic and social conditions in Europe, giving legitimacy to neo-fascist forces like the ones in Ukraine might just be the fuel needed to ignite that racist, fascist delirium Berneri referred to.

Ajamu Baraka is the national organizer of the Black Alliance for Peace and was the 2016 candidate for vice president of the United States on the Green Party ticket. Baraka is an editor and contributing columnist for the Black Agenda Report and was awarded the U.S. Peace Memorial 2019 Peace Prize and the Serena Shirm award for uncompromised integrity in journalism.