Long before the Crusades, through centuries of colonization, to the oil-motivated wars of the present day, land has been the currency of religious, imperial, and national power. Farmers have been made landless by economic and political forces within their own countries, as well as those from far reaches of the globe. Spikes in food prices over recent years have triggered the latest wave of international land grabs, with investment firms snapping up agricultural land, hoping to turn a profit for their investors in the next food crisis. An estimated 50 to 80 million hectares of land have been a part of international investment deals in recent years —approximately two-thirds of them in Africa.

Land and development experts Shalmali Guttal, Maria Luisa Mendonça, and Peter Rosset write, “Fair and equitable access to land and other resources like water, forests, and biodiversity is perhaps the most fundamental prerequisite for… a decent standard of living and… ecologically sustainable management of natural resources.” Today, land access remains largely unfair and inequitable. Never has such a high percentage of the world’s population been displaced from their indigenous or ancestral lands, left without land, a secure home, or the ability to feed themselves.

As the consolidation of land as a private resource for profit-making is global, so is the movement to relate to land in an alternative way, one which meets everyone’s needs. Landless, peasant, family, and indigenous farmers worldwide have long been engaged in land reclamation and land reform movements—either seizing unfairly owned or consolidated land or winning laws mandating redistribution. (The same concepts often underlie the struggle for fair housing.) Examples range from Americans fighting foreclosures as a part of “Occupy Our Homes” to Indians lying down in rows to block corporate tractors encroaching on their villages, Haitians still living in tents since the earthquake two years ago marching for their right to housing, and indigenous Hondurans reclaiming their territories in the face of violent repression.

Newer movements have much to learn from groups that have been mobilizing for decades, such as the Movement of Landless Rural Workers (MST by its Portuguese acronym) in Brazil, a country with one of the highest levels of land and income inequality in the world. The MST’s response to poverty, hunger, and landlessness is to put fallow land back into production in the hands of small farmers. It does this by organizing landless, unemployed, and slum-dwelling people to gain legal title to the nation’s vast unused land. Roughly one and a half to two million MST members have created about 2,000 cooperatively-run, democratic communities on tens of thousands of reclaimed acres. On them, they have established their own models of self-government, restorative justice, self-produced media, ecologically sound agriculture, collective production, law, social relations, cultural expression, and education.

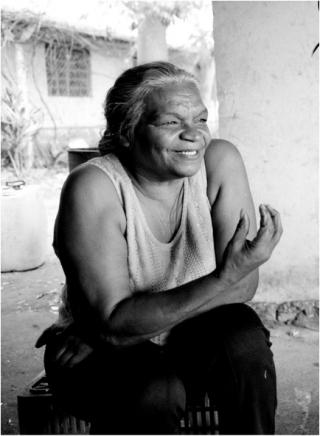

In the second part of the Birthing Justice series, we’ll hear from Ilda Martines de Souza, a leader in the MST. A 64-year-old Tupi-Guaraní farmer, Ilda has been involved in the movement for social and economic justice since she was 18.

Ilda Martines de Souza | São Paulo State, Brazil:

My parents lost their plot of rural land in the ‘60s; the landowner expelled them. After that, we didn’t have anywhere to live. I was young, and I went to São Paulo to try to make money to buy land for my father. I never could, since it was difficult to work and make enough money to buy land.

I got involved with the struggle at a very early age – I was eighteen – and I really liked it. I became an activist with the Workers Party; my children were activists, too. Then, I got involved in the São Paulo housing movement for the homeless and those living in the favelas, the slums. It was really gratifying. Each family you kept off the streets was a great joy.

It was difficult, because this was during the time of the dictatorship and we couldn’t have meetings. We talked with families in soup kitchens, in churches. And we suffered mistreatment because of our organizing. I was kicked out onto the streets from different houses I rented. Then we would occupy another abandoned house and, when we began to organize again, they kicked us out again. But we didn’t let this bring us down, we never lost hope. We had hope that many good things were ahead of us, you know?

Through this, we were able to discover the beautiful MST. We heard people talk about it, but when it was born in São Paulo, I had the great task of organizing to collect food and clothes and coats and medicine that we would take to the countryside. I met the MST activists and leadership. It was still very small at the time, but it was turning into an ants’ nest.

And so I began to integrate myself into the movement, and I met my dream of returning to the countryside. In 1988, I left São Paulo and came to Itapeva to do work with the grassroots. In 1989, I was part of an encampment [a squatter’s settlement demanding land redistribution] with my children, which was a rich experience.

My dream is to see real agrarian reform for all the land, so no child goes hungry, and no mother sheds tears because her son was murdered trying to steal a piece of bread. The pain of a mother is my pain. Every child is my child. I’m not mother to six. I am mother to thousands of youth, of children. I can’t just listen to a mother in pain because her son was murdered in the favelas.

This alternative is based on the dreams of each of us who comes to the countryside to be part of the land reform movement. “How is it that I want my life to be in the country?” We learn that people want a small house, they want to plant different foods, to have a pretty table, to always have enough milk for their children. And to see their kids study and play. That’s what we discover slowly, traveling through the minds and dreams of each human being that becomes part of our settlements. We don’t impose anything on them. We discover that we can share our dream with someone else, unite it with theirs, and begin to construct paradise together.

We want to build this paradise so our children and everyone who comes to the country can step on this land and be proud to say, “Here, we don’t shed blood. Here, we don’t wage war.”

This beautiful thing that comes from the conquest of a piece of land, when we take the land from one hand and put it in the hands of a thousand… it’s a revolution. The land becomes a communal good for everyone, and that is revolution. It’s also a revolution in production. Landowners would only use this land for cattle, and now we produce beans, milk, food, for the entire population.

Without firing a gun, we created a revolution. Without a death toll, we made revolution. Without shedding blood… it’s unnecessary.

The work is also about being honest, worthy, and participating in the local political reality. It’s about democratic participation of all, so that we can get out of the cruel reality that most people live in Brazil.

One thing that women don’t realize is our strength. Mothers are the stars that will guide their children. When a mother gains her consciousness, she creates a rainbow, because she works and struggles with all her heart to guarantee that her children, and her children’s friends, accompany her.

I am so proud to be a woman and to see women struggling, because I know that’s where the future lies. If I were born ten times, and I had a say-so, I would want to be born a woman every time. The most marvelous thing this life has to offer is a woman’s consciousness. She’s creative. She doesn’t lose the beauty of being a woman, no matter where she happens to be. That is one of the things each of us should be most proud of, to set our feet on the ground and declare: I am a woman.

What I have gained throughout the years the movement has given me… To raise all my kids here in this piece of land, in this paradise: that’s my pride and joy. And today, what I have to do is contribute to the MST, to help construct other paradises for other families.

To learn more about Ilda Martines de Souza’s organization, Landless Rural Workers Movement, please see www.mstbrazil.org.

Inspired? Here are a few suggestions for getting involved!

- Support the Landless Rural Workers Movement of Brazil (MST) through the Friends of the MST (www.mstbrazil.org).

- Land reform takes on a new meaning in the US as banks foreclose on family homes and farms, and the US government shies away from providing public housing. US Human Rights Network’s Take Back the Land Campaign organizes in eight cities to house people displaced by the destruction of public housing, foreclosures, and other means of forced eviction. For more information visit their website or contact [email protected].

- Join a national call in the US for a moratorium on all foreclosures and home evictions. Join or start a local campaign to protest evictions in your community. Learn more from the National Fair Housing Alliance (www.nationalfairhousing.org).

And check out the following resources and organizations:

- Land Research Action Network, www.landaction.org

- Peter Rosset, Raj Patel, and Michael Courville, Promised Land: Competing Visions of Agrarian Reform (Food First, 2006)

- Sue Brandford and Jan Rocha, Cutting the Wire: the Story of the Landless Movement in Brazil (Latin American Bureau, 2002)

- Angus Wright and Wendy Wolford, To Inherit the Earth (Food First Books, 2003)

- Max Rameau, Take Back the Land: Land, Gentrification and the Umoja Village Shantytown (Nia Press Progressive Publishing, 2008)

- Jaron Browne et al., Towards Land, Work & Power: Charting a Path of Resistance to U.S.-led Imperialism (United to Fight Press, 2005)

Discover more ideas and download the entire Birthing Justice series here.