BREAKING: Activists in Atlanta say that police are lying about what happened when a protester was shot and killed Wednesday.

The activists say police were hit with friendly fire when raiding their encampment, and that the activist killed, Tort, did not shoot them. pic.twitter.com/7U5JrkTj8k

— BreakThrough News (@BTnewsroom) January 20, 2023

Related Articles

Related Articles

‘Anti-Black’ Claim Raised About Cuba As Solidarity Activists Stopped at U.S. Border & Black Socialists Arraigned in United States for Collaborating with Russia

A 2-year-old argument about “anti-Blackness” in Cuba, which Black solidarity activists in the United States say has no basis in reality, has reared its head.

It appeared in a video posted on Twitter on May 1 that has since gone viral, generating more than 2 million views in four days. The video features Afro-Cuban Grecia Ordoñez, who claims Cuban Revolution leaders Fidel Castro and Ernesto “Che” Guevara were racists who engaged in “white saviorism.” She also claimed genocide was committed in the Democratic Republic of Congo during the time Cuba’s revolutionary government intervened to support rebels fighting the DRC government put in place after revolutionary leader and first Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was assassinated in 1961. Further, she pointed to Afro-Cubans being detained in Cuba as an example of racism.

A message to black Americans from Cubans regarding Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. #Cuba🇨🇺 pic.twitter.com/kHCDnBaE6H

— Martha Bueno (@BuenoForMiami) May 1, 2023

Activists debunked her claims on Twitter, including a thread of articles and videos featuring members of anti-imperialist group Black Alliance for Peace.

For 2 years, the “anti-Blackness” claim has allowed "human rights" narratives to form around revolutionary states in the crosshairs of the U.S. empire. This video comes on the heels of one of the largest U.S. youth delegations to visit #Cuba (@PeoplesForumNYC). Here's a thread 🧵 https://t.co/oV3AhE9V0u

— Black Alliance for Peace (@Blacks4Peace) May 4, 2023

The thread included the following articles and videos:

- Hood Communist Guide to the U.S. Blockade

- Limits of Lived Experience by Erica Caines

- Out of The Clouds: Remarks on Anti- Blackness In Cuba by Salifu Mack

- Witnessing Afro Cubans and Social Change by Austin Cole

- An African Palenque: Cuba And Global Black Solidarity by Kimberly Monroe

- African Power and Politics In Cuba’s La Marina Neighborhood by Musa Springer

- Ajamu Baraka on Cuban Protests

- Afro-Cubans Against Cuba

- Black Alliance For Peace x Belly of The Beast Screening Event

- James Early and Musa Springer on Cuba, Socialism and Race

- Black August and The Cuban Revolution

While Ordoñez doesn’t point to evidence for the claim about genocide in Congo, a 2021 article in the Journal of Cold War Studies states:

“In reality, the main purpose was to crush the rebellion and secure Western interests in Congo. The intervention reflected a cavalier attitude toward sovereignty, international law, and the use of force in postcolonial Africa and had the adverse effect of discrediting humanitarian reasoning as a basis for military intervention until the end of the Cold War. The massacre of tens of thousands of Congolese in Stanleyville was a unique moment in which African countries united in their criticism of Western policies and demanded firmer sovereignty in the postcolonial world.”

Black Activists Reject Claims of Cuba’s Racism

The Black Alliance for Peace released a statement close to two years ago after protests erupted in Cuba over claims of racism. The statement, titled, “Biden’s Commitment to U.S. White Power Is the Real Race Issue in Cuba,” concludes, “We say to all those who pretend to be concerned about Cuba to demand an end to the embargo and to respect the right of the Cuban people to work through their own problems. As the first republic established on the basis of race and subsequently invented apartheid, the United States should be the last on the planet to lecture anyone on race relations.”

Activists like Asantewaa Nkrumah-Ture raised her voice against the claim that Cuba holds Black political prisoners.

“Who are ‘Black political prisoners’ in Cuba? What are their names? What organizations do they belong to & are those organizations independent of [U.S. National Endowment for Democracy] NED and [U.S. Agency for International Development] u.s. AID? Do they belong to [movement of jailed dissidents] Ladies in White? LOL, you sound more & more like Carlos Moore,” Nkrumah-Ture tweeted. Moore is an Afro-Cuban academic who wrote a 1988 book criticizing Cuban leader Fidel Castro as using racist means to grow Cuba’s influence around the world.

Who are "Black political prisoners" in Cuba? What are their names? What organizations do they belong to & are those organizations independent of NED and u.s. AID? Do they belong to Ladies in White? LOL, you sound more & more like Carlos Moore 🇨🇺

— Mawusi Ture (@MawusiTure) May 4, 2023

Further, activist and Ph.D. candidate Kimberly Miller tweeted in reply, “Are the ‘Black political prisoners’ you’re referring to leaders of San Isidro ‘movement,’ like Luis Alcántara or Denis Solís, who admittedly had members ‘who love Trump’ and directly met w/charge d’affaires at U.S. Embassy in Havana to foment regime change??”

are the “Black political prisoners” you’re referring to leaders of San Isidro ‘movement’ like Luis Alcántara or Denis Solís who admittedly had members “who love Trump” and directly met w/chargé de affaires at US Embassy in Havana to foment regime change?? https://t.co/NUpR919H9X

— Kimberly-Dawn 🇸🇩 (@ComradeKimDawn) May 5, 2023

U.S. Solidarity Activists Detained After Visit to Cuba

Meanwhile, Ordoñez’s viral video came just as the largest solidarity delegation in recent history commemorated May Day or International Workers’ Day, alongside 100,000 Havana residents representing many sectors of work. Last year’s parade drew 700,000 Cubans in Havana, as well as thousands of people who celebrated across the island. However, this year, the more-than-60-year-old U.S. blockade on Cuba has caused fuel shortages that required Cuba to cancel the parade itself and instead organize events in Havana’s neighborhoods, as Musa Springer reported on Radio Sputnik’s “By Any Means Necessary,” co-hosted by TF Board Secretary Jacqueline Luqman.

“Cubans say they are in a second Special Period,” Springer said, referring to the first Special Period that occurred after the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, thereby causing drastic shortages of food, fuel and machinery in the 1990s. Cuba’s gross domestic product thus dropped by 35 percent in three years.

More than 1,000 foreigners from 58 countries, all representing 271 youth, labor, social and political organizations traveled into Cuba this year for the parade, as well as for an annual conference held the next day. The delegation, led by People’s Forum in New York City, included between 300 and 350 U.S.-based activists, including many young people who had never been to Cuba before. The People’s Forum tweeted that their delegation faced a second questioning behind closed doors upon their return to U.S. airports and that their digital devices had been confiscated for searches.

Upon arrival to U.S. airports, U.S. citizens and non-citizens usually line up at booths to be questioned by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol officers. Most people are allowed to continue into the United States after answering a few questions about the reason for their journey abroad. Any reason can provoke a second questioning in private, which can extend a traveler’s time inside the airport by hours.

Activist Bill Hackwell wrote in Resumen Latinoamerica English that both members of the International Peoples Assembly delegation and the LA US Hands Off Cuba Committee delegation faced a second round of interrogations, as well as device confiscations. At the time of his writing, members in those delegations had been freed.

Hackwell commented on the irony by remarking on his experience in Cuba.

“What I have seen this past week is a government here more concerned about the well-being of the next generation of U.S. youth than their own government that marginalizes them by constricting access to jobs with a living wage, that makes access to education nearly impossible without the burden of student loans that they will carry for years, and that incarcerates them at a rate like no other country in the world.”

Manolo De Los Santos, executive director of the People’s Forum, thanked the Cuban people for their solidarity.

“These unfortunate incidents are further evidence of the wrong direction of a hostile U.S. foreign policy towards Cuba,” De Los Santos concluded in the tweet. “Their actions in fact demonstrate that the U.S. is far from a bastion of democracy and human rights, and rather than intimidate us, they motivate us to strengthen our struggles for true, transformative change here in the United States.”

🇨🇺✊🏽 After hours of harassment & interrogation, all the comrades who traveled to Cuba are FREE! Thanks for all the love & solidarity received from throughout the world!!

The aggressive attitude of the Customs & Border Patrol officials towards the members of our delegation during…

— Manolo De Los Santos (@manolo_realengo) May 4, 2023

Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez expressed his solidarity with the detained activists.

“Cheer up guys, we’re with you. Thank you for your courage, for supporting #Cuba and for facing the hatred of those who cannot stand the fact that the Cuban Revolution has the support of the most progressive youth in the very bowels of the beast. We send you a big hug.”

Ánimo, muchachos, estamos con ustedes. Gracias por la valentía, por apoyar a #Cuba y por enfrentar en las propias entrañas del monstruo el odio de quienes no pueden soportar que la Revolución Cubana tenga el apoyo de los jóvenes más progresistas. Les mandamos un fuerte abrazo. https://t.co/N6K2H92CaX

— Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez (@DiazCanelB) May 4, 2023

U.S. Government Attacks Black Socialists

Meanwhile, the Hands Off Uhuru campaign announced via email to the press that on Tuesday, May 2, African People’s Socialist Party Chairman Omali Yeshitela and African People’s Solidarity Committee Chairwoman Penny Hess appeared in federal court in Tampa, Florida, in response to the U.S. Dept. of Justice’s April 18 indictment. The Black socialist group is accused of allegedly attempting to “sow discord” in the United States with the support of Russia.

Yeshitela, an 81-year-old Black man, and Hess, a white woman active in the movement since 1976, were “booked, restrained with handcuffs and leg irons, and held in a cell for several hours before appearing before a judge who released them on conditional bond that included a requirement to hand over their passports.

On Monday, May 8, Uhuru Solidarity Movement Chair Jesse Nevel will appear in response to the same indictment.

The group has asked the public to donate to the “Hands Off Uhuru! Hands Off Africa! Defense Fund” to help cover their legal fees.

Background information about this indictment can be found in a recent Toward Freedom article. If found guilty, the accused face up to 15 years in prison.

Julie Varughese is editor of Toward Freedom.

Morocco Drives a War in Western Sahara for Its Phosphates

Editor’s Note: The following represents the writer’s analysis about a disputed area known as “Western Sahara” and was produced by Globetrotter.

In November 2020, the Moroccan government sent its military to the Guerguerat area, a buffer zone between the territory claimed by the Kingdom of Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). The Guerguerat border post is at the very southern edge of Western Sahara along the road that goes to Mauritania. The presence of Moroccan troops “in the Buffer Strip in the Guerguerat area” violated the 1991 ceasefire agreed upon by the Moroccan monarchy and the Polisario Front of the Sahrawi. That ceasefire deal was crafted with the assumption that the United Nations would hold a referendum in Western Sahara to decide on its fate; no such referendum has been held, and the region has existed in stasis for three decades now.

In mid-January 2022, the United Nations sent its Personal Envoy for Western Sahara, Staffan de Mistura, to Morocco, Algeria and Mauritania to begin a new dialogue “toward a constructive resumption of the political process on Western Sahara.” De Mistura was previously deputed to solve the crises of U.S. wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria; none of his missions have ended well and have mostly been lost causes. The UN has appointed five personal envoys for Western Sahara so far—including De Mistura—beginning with former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker III, who served from 1997 to 2004. De Mistura, meanwhile, succeeded former German President Horst Köhler, who resigned in 2019. Köhler’s main achievement was to bring the four main parties—Morocco, the Polisario Front, Algeria and Mauritania—to a first roundtable discussion in Geneva in December 2018: this roundtable process resulted in a few gains, where all participants agreed on “cooperation and regional integration,” but no further progress seems to have been made to resolve the issues in the region since then. When the UN put forward De Mistura’s nomination to this post, Morocco had initially resisted his appointment. But under pressure from the West, Morocco finally accepted his appointment in October 2021, with Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita welcoming him to Rabat on January 14. De Mistura also met the Polisario Front representative to the UN in New York on November 6, 2021, before meeting other representatives in Tindouf, Algeria, at Sahrawi refugee camps in January. There is very little expectation that these meetings will result in any productive solution in the region.

Abraham Accords

In August 2020, the United States government engineered a major diplomatic feat called the Abraham Accords. The United States secured a deal with Morocco and the United Arab Emirates to agree to a rapprochement with Israel in return for the United States making arms sales to these countries, as well as for the United States legitimizing Morocco’s annexation of Western Sahara. The arms deals were of considerable amounts—$23 billion worth of weapons to the UAE and $1 billion worth of drones and munitions to Morocco. For Morocco, the main prize was that the United States—breaking decades of precedent—decided to back its claim to the vast territory of Western Sahara. The United States is now the only Western country to recognize Morocco’s claim to sovereignty over Western Sahara.

When President Joe Biden took office in January 2021, it was expected that he might review parts of the Abraham Accords. However, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken made it clear during his meeting with Bourita in November 2021 that the U.S. government would continue to maintain the position taken by the previous Trump administration that Morocco has sovereignty over Western Sahara. The United States, meanwhile, has continued with its arms sales to Morocco, but has suspended weapons sales to the United Arab Emirates.

Phosphates

By the end of November 2021, the government of Morocco announced that it had earned $6.45 billion from the export of phosphate from the kingdom and from the occupied territory of Western Sahara. If you add up the phosphate reserves in this entire region, it amounts to 72 percent of the entire phosphate reserves in the world (the second-highest percentage of these reserves is in China, which has around 6 percent). Phosphate, along with nitrogen, makes synthetic fertilizer, a key element in modern food production. While nitrogen is recoverable from the air, phosphates, found in the soil, are a finite reserve. This gives Morocco a tight grip over world food production. There is no doubt that the occupation of Western Sahara is not merely about national pride, but it is largely about the presence of a vast number of resources—especially phosphates—that can be found in the territory.

In 1975, a UN delegation that visited Western Sahara noted that “eventually the territory will be among the largest exporters of phosphate in the world.” While Western Sahara’s phosphate reserves are less than those of Morocco, the Moroccan state-owned firm OCP SA has been mining the phosphate in Western Sahara and manufacturing phosphate fertilizer for great profit. The most spectacular mine in Western Sahara is in Bou Craa, from which 10 percent of OCP SA’s profits come; Bou Craa, which is known as “the world’s longest conveyor belt system,” carries the phosphate rock more than 60 miles to the port at El Aaiún. In 2002, the UN’s Under-Secretary General for Legal Affairs at that time, Hans Corell, noted in a letter to the president of the UN Security Council that “if further exploration and exploitation activities were to proceed in disregard of the interests and wishes of the people of Western Sahara, they would be in violation of the principles of international law applicable to mineral resource activities in Non-Self-Governing Territories.” An international campaign to prevent the extraction of the “conflict phosphate” from Western Sahara by Morocco has led many firms around the world to stop buying phosphate from OCP SA. Nutrien, the largest fertilizer manufacturer in the United States that used Moroccan phosphates, decided to stop imports from Morocco in 2018. That same year, the South African court challenged the right of ships carrying phosphate from the region to dock in their ports, ruling that “the Moroccan shippers of the product had no legal right to it.”

Only three known companies continue to buy conflict phosphate mined in Western Sahara: Two from New Zealand (Ballance Agri-Nutrients Limited and Ravensdown) and one from India (Paradeep Phosphates Limited).

Human Rights

After the 1991 ceasefire, the UN set up a Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). This is the only UN peacekeeping force that does not have a mandate to report on human rights. The UN made this concession to appease the Kingdom of Morocco. The Moroccan government has tried to intervene several times when the UN team in Western Sahara attempted to make the slightest noise about the human rights violations in the region. In March 2016, the kingdom expelled MINURSO staff because then-UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon referred to the Moroccan presence in Western Sahara as an “occupation.”

Pressure from the United States is going to ensure that the only realistic outcome of negotiations is for continued Moroccan control of Western Sahara. All parties involved in the conflict are readying for battle. Far from peace, the Abraham Accords are going to accelerate a return to war in this part of Africa.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is the chief editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest book is Washington Bullets, with an introduction by Evo Morales Ayma.

Wealthy Countries ‘Disappoint’ on Climate Funding, Seek to Change Criteria for Financial Support

Correction: A previous version of this article stated the United States owed a greater amount to the UN’s climate finance program.

If anyone expected ambitious delivery of climate finance given the rhetoric at the United Nations’ 26th Conference of Parties (COP26), they would be disappointed. Ongoing discussions regarding climate funding to help developing countries meet their obligations reveal serious limitations, according to experts Toward Freedom interviewed.

A meeting was held March 8-9 to discuss the next round of funding for the Global Environment Facility (GEF) Trust. The trust was established in 1992 to support developing countries to comply with international environmental conventions and agreements, like those related to climate change, biodiversity, chemicals, and waste and food security. Currently, discussions are on for the eighth round of funding.

Wealthy Countries’ ‘Ambitious Regression’

As of now, it looks like funding for climate action will be around $1 billion. This is only marginally better than the seventh replenishment cycle that allocated $800 million, about $200 million less than the sixth cycle.

“This is what ambitious regression looks like,” said Zaheer Fakir, one of the lead coordinators for the African Group of Negotiators on Climate Change (AGN).

Moreover, certain developed countries like the United States, Japan and Switzerland have proposed smaller allocations toward climate change in the GEF, while prioritizing other items like biodiversity and chemicals. Their argument is that while other entities—like the Green Climate Fund—could mobilize climate funding, GEF is the only grant-based, multilateral financing mechanism for other issues like biodiversity loss and chemical waste.

But developing countries don’t share this view, according to Fakir. Speaking for South Africa, he said the GEF should ideally scale up allocations for all areas—including climate change—because it is an entity through which funding is provided under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), too.

This is in line with an October 2020 COP guidance to the GEF that encourages GEF, as part of its eighth replenishment process, “to duly consider ways to increase the financial resources allocated for climate action” and calls upon developed country parties to “contribute to a robust eighth replenishment… to support developing countries in implementing the Convention…” The guidance note also specifically invites GEF “to duly consider the needs and priorities of developing country Parties when allocating resources to developing country Parties.”

In fact, the Memorandum of Understanding between COP and GEF explicitly states GEF policies, program priorities and eligibility criteria related to UNFCCC shall be decided by the COP.

“All developing countries, be it in Africa or Asia or Latin America are calling for an increase in overall GEF funding because there are legitimate needs for climate action and also other areas like biodiversity,” said Kamal Djemouai, an independent climate consultant from Algeria and former AGN chair. “We need new and additional finance for all areas from climate change to biodiversity to land management.”

The United States has pushed to keep current funding low, despite owing $102.4 million to the GEF for previous replenishment cycles.

The other issue is donor-dictated policies. Fakir explained that GEF policies, country allocations and focal area programming are dictated by developed country contributors that are donors to the trust. Djemouai agreed, saying allocations to the GEF “do not reflect the needs of developing countries or even the guidance given by COPs.”

GEF Chief Executive Officer and Chairperson Carlos Manuel Rodriguez declined to reply to this reporter’s questions.

The United States Disappoints

The other recent blow to expectations of increased climate finance delivery came last week when the United States allocated $1 billion toward international climate finance for fiscal year 2022. U.S. President Joe Biden had promised to deliver $11.4 billion each year by 2024.

“Hopes were raised quite high, but the allocation fell severely short. So yes, it is disappointing,” said Joe Thwaites, an associate of the Sustainable Finance Center at the World Resources Institute. He pointed out that, at this rate, it would take up to the year 2050 for the United States to meet its target of $11.4 billion per year unless the 2023 U.S. spending bill allocates substantially more toward international climate finance.

The United States also has not set aside money for the Green Climate Fund (GCF). GCF mobilizes funding to enable developing countries to adapt to a rapidly warming world. This comes as the United States still owes $2 billion to GCF out of U.S. President Barack Obama’s pledge of $3 billion.

An Unfair Advantage for Some Island Nations?

Policy recommendations from the February 2-4 GEF meeting suggest support for introducing a “Vulnerability Index” to replace the GDP index used as the criteria to access climate finance. This has given rise to concerns among certain developing countries that climate funding for poorer nations could instead go to richer ones.

On March 18, Brazil, India, Mexico, South Africa, China and Latin American countries released a joint statement raising concerns about the Vulnerability Index. The term “vulnerable countries” is not part of any multilateral environmental agreements for which GEF is the financing mechanism. Currently, the only categorization is “developed” and “developing.”

The GEF must “continue to treat all developing recipient countries equally and, in this regard, must not introduce new categories of countries or to provide for any differentiation or graduation among developing countries for accessing its financial resources or financial terms,” the statement argued.

This policy recommendation follows a previously made demand at UNGA to use a Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI) for small island developing states (SIDS) to access concessional financing, or grant funding.

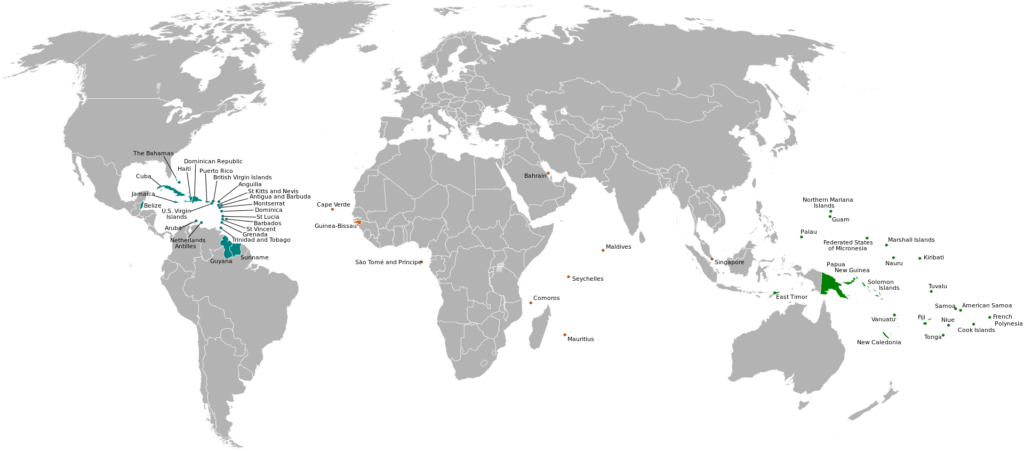

Small islands are vulnerable to climate change impacts. But it could be considered unfair to rank SIDS that are high-income or even upper-middle-income countries, like Mauritius and St. Lucia, higher than least developed countries, like Mozambique, Yemen and Afghanistan. A higher ranking would open the path to lower interest-rate loans.

The United Kingdom, too, favors reworking the criteria. Geopolitical considerations like accommodating Caribbean islands post-Brexit to offer the Commonwealth as an alternative to the European Union might play a role.

The GEF is holding another meeting for discussions on the eighth replenishment in the first week of April.

Rishika Pardikar is a freelance journalist in Bangalore, India. She had reported for Toward Freedom from COP26 in Glasgow.