Moroccan journalist Soulaiman Raissouni was recently one of many writers in the country who took refuge on the internet after he was sidelined and silenced by his editors for his critical coverage of the Moroccan government.

Raissouni said editors punished him for a report he filed on the management of a cultural festival in the town of Asilah. The article, he said, had angered the municipality’s leaders.

Two years ago, after being marginalized at the newspaper Al Massae, one of Morocco’s biggest dailies, and not assigned any stories for seven months, Raissouni decided to leave the paper with a colleague and set out on his own.

He started his own news website, Al Aoual, which has given a voice to people generally not seen in the pro-government media, including those critical of the government, opposition figures, and activists.

Although he is now relatively free to decide which subjects he can cover, Raissouni, like most journalists in Morocco, is forced to stay away from topics that are deemed too sensitive, and to second guess each word he writes.

Most journalists admit they do not cross certain “red lines” in Morocco. These lines include critical coverage of Morocco’s king and his advisers, Morocco’s sovereignty over the Western Sahara territory, Islam, and another line that has progressively become more dangerous to cross, the economic Makhzen (Morocco’s state and administration), meaning big names in business close to the monarchy.

These lines are not precisely defined in any official law. Journalists are therefore forced to go around these subjects as far as they can, leaving them and their editors to assess the risk they are willing to take. These poorly defined red lines are not only for journalists, but for everyone. Human rights defenders in Morocco further insist such crackdowns are in contradiction with the constitution passed in 2011 to quell pro-democracy protests; the document guarantees freedom of expression.

Moroccan journalists know what they risk when they go too far and are forced to self-censor. While no Moroccan official would admit this is the case, the government sends clear messages to journalists about how they should conduct their work. For example, some journalists say they face police harassment for their reporting, while others are sued or face jail time. Press freedom has further weakened in Morocco because journalists and editors suffer advertising boycotts and defamation when they come too close to the red lines.

As a result, in the 2017 Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index, Morocco ranked 133rd out of 180 countries.

In order to survive and keep one’s job, self-censorship is mandatory in Morocco’s news business, according to Raissouni. “I cannot write everything I want. Everybody does self-censorship to different degrees,” he admitted. He says he therefore uses rhetoric, metaphors or symbols, when he writes, in order to “say and not say things.”

Even though today it seems more acceptable than before to indirectly address the monarchy, Raissouni regrets that new taboos have emerged, with personalities in the king’s entourage that cannot be criticized in the press.

Among those who journalists cannot criticize, Raissouni gave the examples of Aziz Akhenouch, one of Morocco’s top businessmen who is also the Minister of Agriculture, and Anas Sefrioui, a major businessman and president of the real estate company Addoha. Addoha sued Al Aoual for 500,000 USD for defamation and invasion of Sefrioui’s privacy after the outlet ran an article on the financial difficulties of the company. According to Raissouni, the website was sentenced to pay 150,000 Dirhams (About 15,000 USD) and the case is currently on appeal.

The numerous leading newspapers and magazines in Arabic sold in Morocco’s streets – such as Al Massae or Al Akhbar – whose editors depend on their advertising revenues, do not generally cross the red lines.

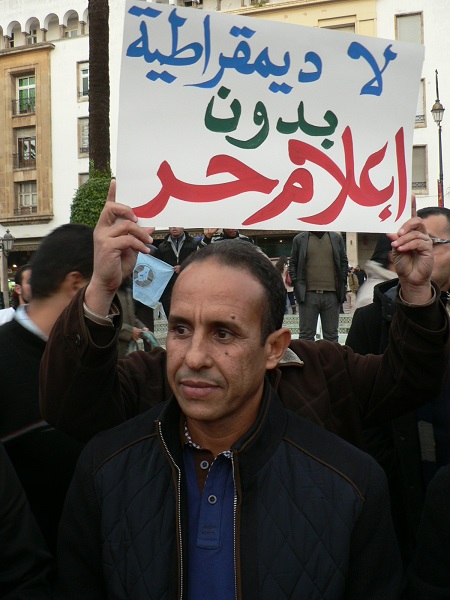

As a result, over the years Moroccans have turned to the web – including Facebook, Youtube, and Twitter – to become truly informed. And many journalists have gone online in order to work more freely and escape financial constraints. Social media has played a particularly powerful role in popularizing and spreading information about protests movements in Morocco.

Morocco’s investigative journalism flourished in the late 1990s and early 2000s at the end of King Hassan II’s reign and the beginning of King Mohammed VI’s. At that time, weekly newspapers like Le Journal, closed in 2010, as well as Telquel, (which is now a dull version of what it once was), covered sensitive subjects and did investigative journalism. At the end of Hassan II’s reign, a relative democratic political opening translated into a new government that included former opponents in its leadership, improvements in human rights, a freer press, and the release of political prisoners.

Since the early 2000s – although the decline has been progressive until 2011, with the Arab Spring – such investigative work in Morocco has progressively diminished due to reporters avoiding sensitive subjects. In 2011, a more open press, especially on the internet, echoed the new freedom won in Morocco’s streets. But another repressive wave initiated in 2013 when the February 20 Movement, which led the protests in the wake of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions, weakened.

“Year after year, I have felt the situation deteriorating, especially after the February 20 Movement window closed,” said Raissouni.

Today, this repression has intensified. Since the beginning of Al Aoual, Raissouni has been smeared in pro-government websites, while his newspaper has been sentenced to pay heavy fines for its critical coverage of leading businesses.

Moroccan journalists’ situation has worsened as of last year, Raissouni stresses, alluding to the arrest of several journalists who covered social movements against political corruption and for more economic development in the Rif, in the north of the country.

Moroccan authorities went a step further in silencing the press when they started arresting reporters, mostly citizen journalists, for reporting on the demonstrations in the Rif, and charging them as if they were part of the protest movement. Eight journalists working for local websites have been jailed since a government crackdown was initiated last May.

Concerns among human rights groups have risen over the accusations journalists are facing. They are charged under Morocco’s penal code, not the new press law passed in 2016, which does not contain prison sentences for journalists.

The citizen journalists arrested and currently tried together with members of the protest movement are Mohamed el-Asrihi and Jawad Sabiri of the Rif24 news website, Abdelali Haddou of Araghi TV, Rif Presse photographer Houssein al-Idrissi, Fouad Assaidi of Awar TV, and Rabie al-Ablaq, a local correspondent for the Badil Info news site, which has since been shut down.

Mohamed Hilali, the director of Rif Presse, was sentenced last June to five months in prison for “insulting police officers in the course of their work” and “demonstrating without prior authorization,” but was granted royal pardon a month later by King Mohammed VI.

Hamid Mahdaoui, the editor of the news website Badil, whose popular and widely-shared video commentaries are critical of the government, denounced the recent repression of activists and the lack of human rights in the country. Mahdaoui was arrested on July 20th and has been sentenced to one year in jail for inciting protests. In another trial, he is currently being tried for “failure to denounce a crime threatening national security,” and faces a five-year sentence.

Mahdaoui has already had judiciary problems before. In 2015, he received a four-month suspended sentence when he reported on the death of Karim Lachkar, an activist from El Hoceima who died in May 2014 under controversial circumstances after being arrested by police.

Ali Anouzla is one of Morocco’s best-known journalists and editor of the news website Lakome 2, created in 2015. Anouzla is one of the rare journalists who used to ignore the red lines. Like other journalists who struggle to remain independent and who are too critical of the government, Anouzla is labeled an “activist” by pro-government journalists as a way to dismiss his work and views.

Anouzla’s audacity led him to pay a heavy price. In October 2013, he was jailed under the anti-terrorism law and was incarcerated for 39 days for “inciting terrorism” after publishing an article that included a link to a blog from the Spanish daily El Pais, which itself linked to a video of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb which threatened to strike Morocco. After Anouzla’s release, the trial was postponed several times and he has not been able to reopen the Lakome website, which he had shut down out of precaution during his stay in prison. To this day, the charges have not been dropped.

Anouzla’s supporters said he had been arrested for his writings, articles in which he went much further than most journalists in critiquing the government. For him, these accusations were excuses for the government to target Lakome’s editorial line. He spoke of issues no other journalists dared to touch at that time: the monarchy and the Sahara issue, for example.

He also reported on what would lead to what is known as the Danielgate scandal: an investigation in the Summer of 2013 over the royal pardoning of a Spanish pedophile in Morocco sentenced to thirty years of jail. The case prompted major protests in the country and led to the king publicly reviewing one of his decisions for the first time.

In 2016, Anouzla encountered new hardships and was accused of undermining Morocco’s territorial integrity when using the expression “the occupied Western Sahara” in an interview with the German newspaper Bild. He denied using it, while the newspaper admitted it was a translation problem and corrected it.

Last month, his trial for inciting terrorism, which dates back to 2013, was postponed once again to this month. Reporters Without Borders called on Moroccan authorities to drop the charges and denounced “a conspiracy” against Anouzla.

Such judiciary pressures put a stranglehold on independent journalists. Any remaining elements of investigative and daring journalism are weakened by the multiplying red lines.

“Red lines have definitely increased,” political analyst Mohamed Chtatou said of the decline of press freedom in Morocco. “At a time, they were adjusted to the minimum. There are so many sacred things now.”

Ilhem Rachidi is a freelance reporter based in Morocco. Rachidi has written extensively on protest movements and human rights issues, publishing articles in the French newspaper Mediapart (where she has worked as a correspondent for four years), Rue89, Al Monitor, and The Christian Science Monitor.