Editor’s note: The following is part four of a series on the history of Toward Freedom.

All segments of the TF history series:

Part One: Waging Peace in the Cold War: Toward Freedom and The Non-Aligned Movement

Part Two: The Non-Aligned Road: Toward Freedom in Africa

Part Three: Fighting Words: Toward Freedom in Africa

Part Four: Paths to Independence: Toward Freedom in Africa

Part Five: The History of America’s “Africa Agenda”: The Role of John Foster Dulles

Toward Freedom editor Bill Lloyd and two of his four children spent ten weeks with him crossing Africa during Fall, 1957. They subsequently published a series of first-hand reports in TF on independence struggles in ten countries. In the process they also met privately with the new leaders of Ghana, the Sudan and Tunisia.

Lloyd called the first article “An Anti-Colonialist Journalist Reports from Inside Africa.” It began with a description of a bus ride in Dakar. A strange theme had emerged in his conversations with several locals. They had spontaneously offered that if the French “won’t give us what we want, we will ask the Americans to come in.”

* * *

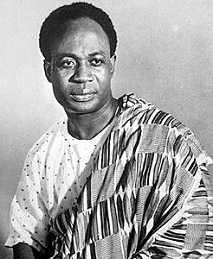

From there they went to Ghana, where Bill obtained an interview with Kwame Nkrumah and listened to his opponents at a large outdoor rally. Being the only Europeans in the crowd attracted considerable attention – until they met an old friend, opposition leader Joe Appiah. As they talked politics others in the crowd stepped closer to listen and offer protection from a light rain with their umbrellas. It was a magic moment.

During that encounter people said they were upset about the deportation of two Muslim leaders. But the government said the two were leaders of a gang that was beating up pro-government organizers. Even some of Nkrumah’s supporters were skeptical about that. Meanwhile, the Minister of the Interior admitted bluntly, “I love power,” and issued more extreme threats.

If so-called “subversive” activity did not stop, he warned the nation, there would be a real dictatorship, complete with concentration camps.

Nkrumah excused that statement, arguing that it was just for local consumption and meant only to scare the opposition. Bill Lloyd’s interview with him was off-the record, but he did write that officials frequently used tribalism and fragmentation as their arguments for a strong, “unitary” government. Basically, he felt they were going too far, trying to mold people along preconceived lines rather than adapt to public needs and desires.

Nevertheless, Lloyd concluded that Ghana was an exciting, hopeful achievement with the potential to inspire the continent.

* * *

In Nigeria he was impressed with the dignity of people in the face of intolerable poverty. It was and remains Africa’s most populous country (161 million, according to the UN), as large as Texas and Nebraska combined. In the late 1950s there were only about 15,000 Europeans in the country, which was inching toward self-government through what Lloyd called “progressive Nigerianization” of administration, the courts and legislature.

But Britain was holding on to certain powers, even over self-governing regions. The goal, for most Nigerians at least, was complete self-government by 1960.

Encountering Inconvenient Truths

The second installment of the series was called “From the Cameroon to Angola.” Lloyd found Douala to be a clean city, with concrete curbing and underground drainage along most streets. But he heard about political repression, despite the country’s status as a Trust Territory.

Why was there only one daily newspaper? “Because the others were suppressed,” replied a clerk. On balance Lloyd concluded that, although people clearly feared reprisals, they were determined to speak out.

Self-government within the French union was supposedly on the horizon. But France could annul any local law or regulation that “impeded” its obligations, or if French and Cameroon law conflicted. In essence, France could prevent any changes it didn’t like.

“If this interpretation prevails,” Bill wrote, “then the scheme is hardly self-government or even autonomy.”

***

In the British Cameroon, despite years of denial, Lloyd learned that plans were still afoot to integrate this “Trust Territory” into Nigeria, a British colony. Important members of the majority party had resigned in protest. Unless people were allowed to freely vote for either unification or independence, he concluded, both Britain and France could be charged with “bartering away the fate of peoples without their consent.”

In French Equatorial Africa, the Lloyds attended a lecture – on desegregation in the US, and at one point Bill offered a few words about reconstruction bitterness after the Civil War. The question period afterward proved to be especially challenging, especially since some who attended felt that recent US progress on race was propaganda designed to help Washington impose its policies on the world.

“As far as discrimination was concerned,” the editor concluded, “we Americans were damned if we did and damned if we didn’t.”

He also noticed that, in some cases, the communists and reactionaries in the crowd were backing each other up. Asked why the US felt justified in getting involved in Africa’s problems when it had serious problems of its own, he considered the question an attempt to silence him and answered with this:

“It’s physically one world, and Africans are justified in observing, if possible, and writing about race relations in the South, just as Americans should be concerned with the morality of what the West does in Africa and, to a more limited extent, with what Africans do in Africa.”

The next stop was Angola, where two Angolan-born African businessmen from Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo told him about the arrest of several hundred former Angolese who had tried to visit from the Congo for a festival. The authorities were apparently concerned that the men, who enjoyed more prosperous conditions than people living in Angola, might spread dissatisfaction and spark a revolt.

In the next installment of Bill Lloyd’s reports from Africa in the late 1950s, he stepped aside for his daughter Robin to tell a story. She used the opportunity to write about an encounter in Southern Rhodesia with Ian Civil, one of her former teachers at the International School in Geneva.

When they arrived Civil was holding and African baby in his arms. As Robin wrote, “Although the government professes partnership between the races, an apartheid almost as strong as their southern neighbors is the actual policy. It is unusual to see a white man and a black man talking on the streets in any manner other than a master-servant relationship. And it is unusual here to see a light man holding a dark baby.”

Foul deeds were occurring, Robin reported. Hospitals were segregated, even the ambulances. They would actually carry away some victims and leave others behind. Civil had seen it himself: a European ambulance driving away when it saw the color of the victims’ skin. One person left behind later died. Civil said some Africans felt the situation was worse than South Africa.

A week after they spoke he was declared a “prohibited immigrant” and deported. No reason was given.

* * *

Next stop, Tanzania, then the UN Trust Territory of Tanganyika. While there Lloyd and company visited the African section of Dar as Salaan to call on Julius Nyerere, president of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). They talked about British attempts to ban the party before an upcoming vote.

The next morning, having just seen the city’s poverty, they witnessed some pomp and glory out of the 19th century during a celebration of Remembrance Day, which was something like the US Veterans’ Day. Officialdom donned their white uniforms and gloves, attended church services, and laid wreaths on two war memorials.

“To one with Quaker tendencies the sight of church ushers wearing swords was a bit of a shock,” Bill wrote.

For a few days Robin and the younger Bill split off from their father’s itinerary to visit the Friends African Mission in Kenya. Bill stayed for a week and later wrote a story for TF.

He had visited the Mission hospital and houses used for TB patients. Although African and European work campers were cordial, he noted that they didn’t socialize much, in part due to language barriers. Nevertheless, he considered it a rare opportunity for different races to work together, one that could lead to better understanding.

* * *

In the Sudan the Lloyds met with Prime Minister Addallah Khalil, who summed up the nation’s three years of independence this way: “We thought we could take independence, but have found that we must build it.”

The meeting had been arranged by Education Minister Nasr Hag Ali, who was a friend of Leon Despres, a Chicago alderman and member of TF’s board.. Ali said the spirit of independence was so pronounced among the country’s largely nomadic population that the government found it difficult to implement regulations.

Bill asked whether reports of Communist influence were true. No, he replied. “The communists are a very small and unimportant group.” On the other hand, he also claimed that although an application had been made for US aid, no “strings” would be accepted.

* * *

The family delegation’s last stop was Tunis. At the time President Bourguiba was helping to mediate between France and Algerian rebels across the border. The Tunisian government was also hosting about 300,000 refugees. The Lloyds met with Bourguiba in his private residence near the ancient site of Carthage.

Bourguiba said the US was losing an opportunity by failing to recognize France’s mistakes in Algeria. He made a comparison with South Vietnam, where the US had backed President Diem over French objections, and predicted that a Saudi Arabian proposal for a provisional Algerian government on foreign soil wouldn’t satisfy the nationalists.

But he conceded that domination of the independence movement by the military was also a problem. “Already they are antagonistic toward intellectuals and civilians,” Bourguiba said, “and you just can’t tell what will happen if things go on as they are now. The longer the war lasts the greater the chance that anarchy will break out.”

Ten weeks after arriving in Africa the Lloyds started home on December 7, 1957. “As we climbed into the clear sky, the beauty of the Gulf of Tunis turned our minds to the possibility of returning sometime as simple tourists with leisure to see the sights,” Lloyd wrote. “And then it was goodbye to a continent that can truly be said to be in crisis – a word which the Chinese very aptly consider a combination of danger and opportunity.”

Greg Guma is an author, editor and the former CEO of Pacifica Radio. He lives in Vermont and writes about politics and culture on his blog, Maverick Media. Guma edited Toward Freedom from 1986-88, and 1994-2004.