Related Articles

Related Articles

U.S. Launched 251 Military Interventions Since 1991, and 469 Since 1798

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in Multipolarista.

The United States launched at least 251 military interventions between 1991 and 2022.

This is according to a report by the Congressional Research Service, a U.S. government institution that compiles information on behalf of Congress.

The report documented another 218 U.S. military interventions between 1798 and 1990.

That makes for a total of 469 U.S. military interventions since 1798 that have been acknowledged by the Congress.

This data was published on March 8, 2022, by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), in a document titled “Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798-2022.”

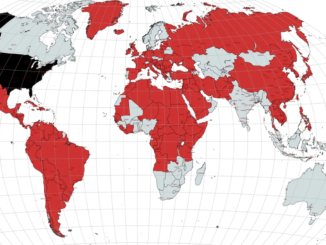

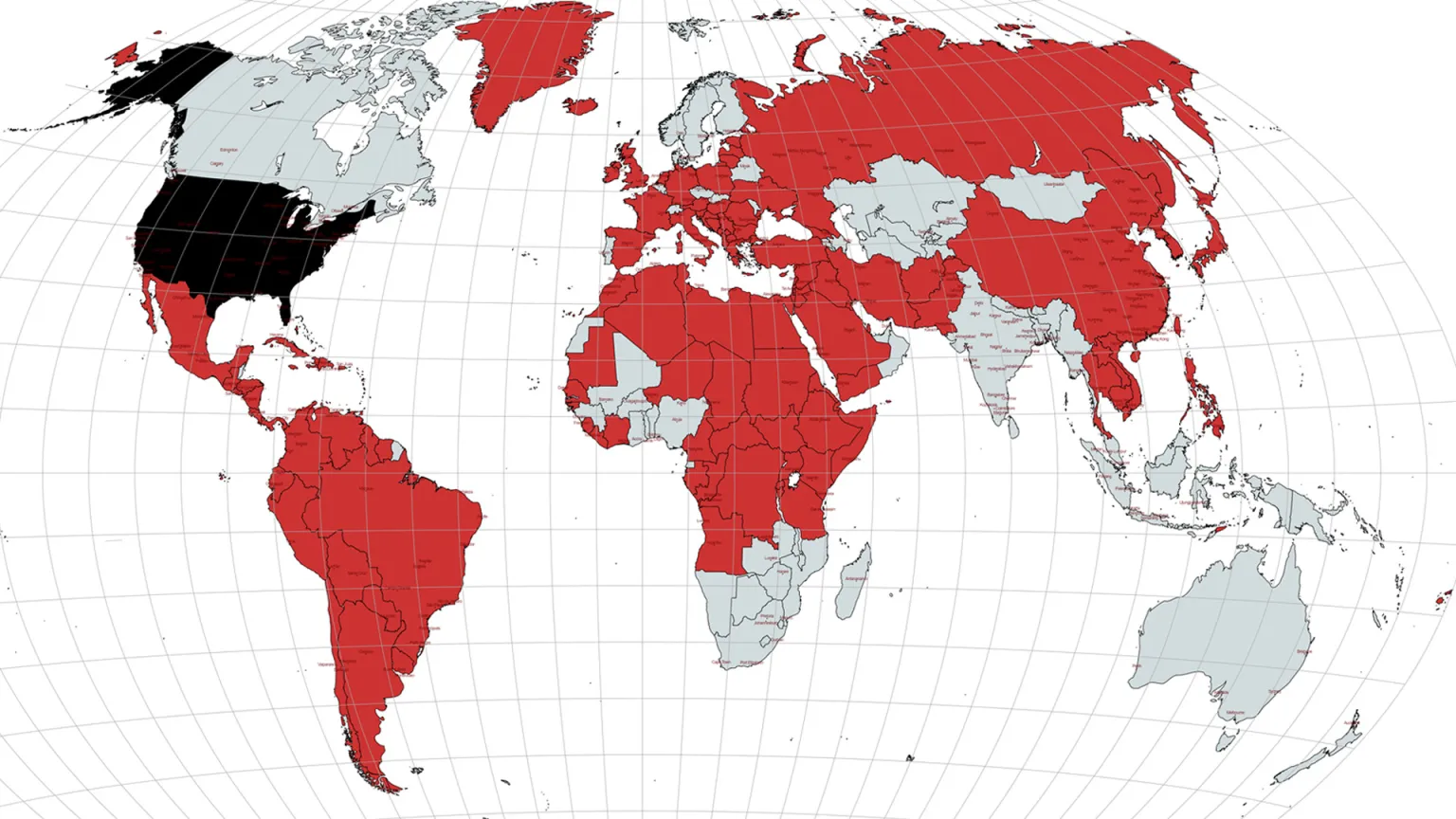

The list of countries targeted by the U.S. military includes the vast majority of the nations on Earth, including almost every single county in Latin America and the Caribbean and most of the African continent.

From the beginning of 1991 to the beginning of 2004, the U.S. military launched 100 interventions, according to CRS.

That number grew to 200 military interventions between 1991 and 2018.

The report shows that, since the end of the first cold war in 1991, at the moment of U.S. unipolar hegemony, the number of Washington’s military interventions abroad substantially increased.

Of the total 469 documented foreign military interventions, the Congressional Research Service noted that the U.S. government only formally declared war 11 times, in just five separate wars.

The data exclude the independence war been U.S. settlers and the British empire, any military deployments between 1776 and 1798, and the U.S. Civil War.

It is important to stress that all of these numbers are conservative estimates, because they do not include U.S. special operations, covert actions, or domestic deployments.

The CRS report clarified:

The list does not include covert actions or numerous occurrences in which U.S. forces have been stationed abroad since World War II in occupation forces or for participation in mutual security organizations, base agreements, or routine military assistance or training operations.

The report likewise excludes the deployment of the U.S. military forces against Indigenous peoples, when they were systematically ethnically cleansed in the violent process of westward settler-colonial expansion.

CRS acknowledged that it left out the “continual use of U.S. military units in the exploration, settlement, and pacification of the western part of the United States.”

The Military Intervention Project at Tufts University’s Center for Strategic Studies has documented even more foreign meddling.

“The U.S. has undertaken over 500 international military interventions since 1776, with nearly 60 percent undertaken between 1950 and 2017,” the project wrote. “What’s more, over one-third of these missions occurred after 1999.”

The Military Intervention Project added: “With the end of the Cold War era, we would expect the U.S. to decrease its military interventions abroad, assuming lower threats and interests at stake. But these patterns reveal the opposite—the U.S. has increased its military involvements abroad.”

Kenya’s Deadly Land Tussles Make Forest Safer Than Houses

MITHIINI, Kenya—Families in a rural Kenyan village have been risking their lives spending most nights in the bushes with snakes and creeping insects to avoid beatings from a group dubbed “The Society.”

“Nobody will attack you in the bush as they will not know where you are,” said Sarah Kanini, who lives in Mithiini village in Murang’a County in central Kenya. The bushes look like a forest mainly consisting of acacia trees. “But in the house, they will just notice when you’re in and when you’re out. We live like wild animals and that is our life.”

Villagers said a private entity called the Mutidhi Housing Cooperative Society has been trying to evacuate the Mithiini families from land they inherited from their ancestors, who had retrieved it from European settler-colonizers. About 2,200 people have been squatting on this land.

Mithiini families lamented to Toward Freedom they have been attacked while struggling for the land since the 1960s. Making matters worse has been what they call a collaboration between government authorities and the Society. Land struggles between squatters and deed holders have continued unabated since Kenya’s 1963 independence from the British empire.

‘I Fear Sitting In My Own House’

Kanini built a house in the village using an aesthetically pleasing combination of varying soils, but she hasn’t been able to enjoy it.

“Even during the day, I cannot spend the time in the house because these people come without a notice,” Kanini told Toward Freedom, adding she was forced last year to bury her mother during odd hours. “I fear sitting in my own house.”

Villagers said the Society burns down houses, uproot plants and beats people. The perpetrators are said to still enjoy their freedom. Villagers provided the name of a senior police officer named Resbon Wafula, who they say collaborates with the Society. Wafula postponed meeting with Toward Freedom a few times. Eventually, this reporter could not reach him by phone. Meanwhile, when an area administrator realized he was speaking with a reporter, he cut off the phone conversation.

Squatters depend on mangoes as a cash crop. However, this reporter witnessed squatters’ trees have been cut down, and stumps either have been uprooted or killed permanently using special chemicals. Grass inside the squatter’s compound the cattle feed on reportedly have been sprayed with herbicide.

“One woman who was a vendor was preparing herself to go to the market,” Kanini said. “But, unfortunately, the attackers cornered her and burned her alive in her own hut—it was shocking.”

When this reporter reached out to area administrator Simon Kinuthia, he denied the issue, saying all squatter cases are taken seriously. He also said he would not comment because court cases are pending and investigations are being conducted. He directed this reporter to the deputy county commissioner, who did not answer his phone.

“Many people have been killed around here, but no action has been taken just because we’re squatters,” said James Mungai, a squatter and a grassroots representative of Defenders Coalition, a Kenya-based non-governmental organization that supports human-rights defenders, including squatters in Mithiini village. “But we’re wondering, even if we’re squatters, still we’re human beings and our rights have been protected by the law.”

Defenders Coalition Director Kamau Ngugi said the group has been working around the clock to ensure squatters’ human rights. However, he said who has the right to the land has remained unclear.

‘Fake’ Deeds and Court Orders

Villagers said the 7,600 acres remain under the name of a European settler named Tom Frazier, who left the country in 1976, leaving the land to the squatters’ ancestors. Some of their ancestors had lived in parts of the land even before Kenya’s independence in 1963.

For instance, Mungai said his mother died in 2015 at the age of 127, having lived on the land her whole life.

According to squatter Francis Kioko, the Society is using “fake” title deeds and “fake” court orders. The squatters have attempted to verify all of the documents the Society has put forth. They have found no basis for the land claims.

Mate Githua, chairperson of the Society, said the Kenyan government had sold the land to the society in 1964. He said a commission under then-president Daniel Moi provided documents stating the land belonged to the Society. After buying the land, Githua said it remained fallow.

“Some people from different areas of Murang’a and Machakos counties started coming in and later claimed that the land belongs to them,” Githua said.

He said the society began dividing the land among Society members in 1988. In 1999, all members were issued title deeds. As a consequence, he said the Society itself doesn’t own land anymore.

“If there is a land problem, then it is between the squatters and members who are now the owners of the land.”

However, Githua said the Society is awaiting a court order to evacuate all squatters from Mithiini.

He denied sending people to beat squatters, saying he had no reason to do that. He declined to disclose the names of the members, saying the Society is a private entity.

‘Only God Will Salvage Us’

For now, the squatters rely on human-rights groups and the media to air their grievances.

Both formerly European settled areas and community settled areas have been lost in the struggle.

Priscilla Wangoi, a squatter and a grassroots representative of Defenders Coalition, said she has visited the country’s highest agencies, such as the Director of Public Prosecution and the Independent Police Oversight Authority IPOA. She said the community awaits a reply from these offices, while this reporter could not reach anyone at the IPOA.

“Only God will salvage us, we’ve nowhere to go and this is the only place that we know as our home,” Kioko said. “We’ve nobody to complain to and we don’t know what they’re planning for us.”

Shadrack Omuka is a freelance journalist based in Kenya. He writes about human rights, climate change, business and education, among other topics. His work has appeared in several publications around the world, such as Equal Times, Financial Mail, New Internationalist, Earth Island and The Continent, among others.

Toward Freedom Seeks an Africa Editorial Consultant

UPDATE: The application deadline has passed.

Toward Freedom, an independent U.S.-based publication, seeks to hire an Africa Editorial Consultant with experience in journalism to help develop a remote Africa Bureau. Check out the requirements and deadline.